The Shadow Canon 04: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass

What does it take to write the greatest children's fiction of all time?

The afternoon of June 17, 1862 did not begin auspiciously for Mr. Charles Dodgson.

At about 12:30pm he embarked from Oxford in a rowboat bound for Nuneham, a landscaped parish of parks and woods shaded with vast oaks. Accompanying him were Robinson Duckworth, a close friend and Fellow of Trinity College, an aunt and two sisters, and three young members of the Liddell family: Edith, Lorina and Alice. These were the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church (where Dodgson was employed as a don) and today probably most famous for co-authoring a standard Greek lexicon. Dodgson had met the Liddell sisters in February 1856 during a riverboat race and had spent the ensuing years amusing them with magic lanterns, odd gifts (he gave one of their brothers a mechanical tortoise) and picnics of lemonade and ginger beer. During lulls in the trips he told stories.

It had been, in many ways, a blissful summer for Dodgson. Since the end of term he had amused himself with croquet games in the Deanery, a boating venture with poet Robert Southey, train trips and village walks. He read the poems of Christina Rossetti, who would become a friend, and submitted a poem of his own to a periodical called College Rhymes[1]. In her later years Alice Liddell, now famous the world over, would recall the visits he made during that spring and summer in the weeks preceding the Nuneham trip:

“He used sometimes to come to the Deanery on the afternoons when we had a half-holiday… When we went on the river for the afternoon with Mr. Dodgson, which happened at most four or five times every summer term, he always brought out with him a basket full of cakes, and a kettle, which we would boil under a haycock, if we could find one. On rarer occasions we went out for the whole day with him, and then we took a larger basket with luncheon—cold chicken and salad and all sorts of good things.” [2]

But the expedition to Nuneham on the seventeenth failed to transpire as planned. They arrived at their destination at around two. As they rowed home down the Thames a couple hours later, they encountered a heavy rainfall. “After bearing it a short time I settled that we had better leave the boat and walk,” Dodgson wrote in his diary.

They were indeed a curious party—Duckworth, the shy, stammering don and his near relations, the bedraggled and increasingly miserable children. Three miles they walked, the rain never letting up, until they arrived at a home belonging to a certain Mrs. Broughton, an acquaintance of Dodgson’s. There the girls warmed themselves while the two older men sought a carriage that would return them to Oxford.

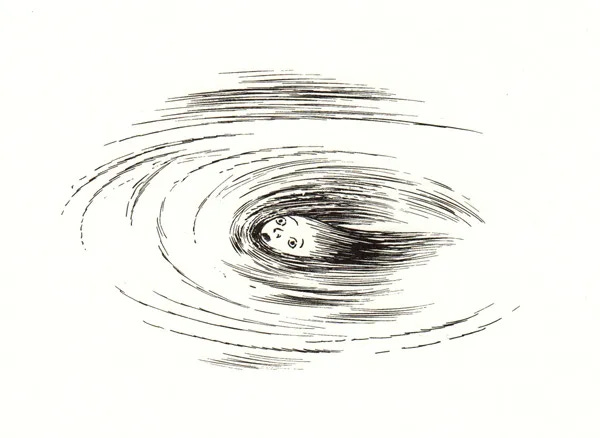

Dodgson—who’d already adopted the pen name “Lewis Carroll” for some of his poems—had a habit of designating his favorite days “white stone days.” “I mark this day with a white stone,” runs a typical entry in his diary. No such designation is appended to the entry for June 17. Biographers seeking the “ground zero” of modern children’s literature tend to locate it in a subsequent boating trip a few weeks later, on July 4, when to amuse the girls Carroll invented a story about a girl named Alice tumbling down a hole after a white rabbit (sending her underground, he would later say, “in a desperate attempt to strike out some new line of fairy-lore”). Yet it’s clear from his diaries, and the later recollections of Alice Liddell and others, that the story of Wonderland was already present, already coming into being, all through that spring and summer. It was there in the landscape of Oxford with its rivers, rolling hills and dense woods. It was there in the imaginative genius of Carroll, who transformed the drenched crew into a throng of “curious creatures”—a duck, a dodo, an eaglet, a lory—emerging from a pool of tears shed by an enormous Alice, and arguing about the most efficient means of getting dry.

“They had a consultation about this, and after a few minutes it seemed quite natural to Alice to find herself talking familiarly with them, as if she had known them all her life. Indeed, she had quite a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say, ‘I’m older than you, and must know better.’”[3]

Thus emerged—not all at once, on a warm day in July, but over many visits during many weeks—a story that would transform the world; a story that would take the genre of children’s fiction, then drowning in stern moralism and treacly sentiment, and pull it into the modern era. Within a few years the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Hatter, the Red Queen and White Queen and Bill the Lizard, the Mock-Turtle and the Tweedle Brothers, would emerge into popular culture like invaders from another realm. They have been with us ever since.

And it all began with a thirty-something Oxford don, retiring and awkward and already acquiring a reputation as a bit of an eccentric, who, unbeknownst to his friends and colleagues, had the power to conjure worlds into being as though from air.

* * *

What makes a good story for children? What sort of tales most engage their attention? “There are common threads,” writes Oxford-based children’s novelist Katherine Rundell, “that run through the children’s books that have endured and the new books that children currently devour. If … I were to draw up a list it would include: autonomy, peril, justice, secrets, small jokes, large jokes, revelations, animals, multitudinous versions of love—and food.”[4] Roald Dahl, while listing various things that kids enjoy seeing in stories (action, treasure, ghosts, magic, grisly deaths), described what he considered the ideal personality for a writer of books for children: They must “have a genuine and powerful wish not only to entertain children but to teach them the habit of reading. He must be a jokey sort of fellow. He must like simple jokes and tricks and riddles and other childish things. He must be unconventional and inventive.”[5]

Dahl might well have been describing Carroll. Born on January 27, 1832 to an Anglican cleric, Charles Dodgson spent his early years at Daresbury Parsonage, getting acquainted with the creatures that would later find their way into his books: rabbits, cats, caterpillars, the flowers in the garden. He “numbered certain toads and snails among his intimate friends,” writes Morton Cohen, and “tried to encourage civilised behavior among earthworms.”[6] Though the Dodgsons were by most accounts a conventional upper-middle-class family, there was a streak of eccentricity running through it. Bizarrely for the time, only three of his ten siblings married. Well into adulthood his sister Louisa sometimes became so absorbed in mathematical puzzles that she failed to notice others. Another sister, Henrietta, acquired some notoriety within the family for her strange behavior. Late in life she moved to Brighton, where she amassed a truly shocking number of cats. She was accompanied on trips by a portable stove so that she could fry sausages, and once in a fit of absent-mindedness accidentally brought an alarm clock to church. (“I like her,” wrote a friend of Carroll’s in her diary. “I think she is like him.”)[7]

At the age of eleven Carroll moved with his family to Yorkshire, his father having been given the rectory manor of Croft-on-Tees. His stammer and partial deafness made adolescence difficult. Under the influence of his mother, with whom he remained close until her early death, he cultivated a deeply felt religious devotion and a series of niche interests. He memorized poems, built his own marionette theatre and wrote a comic opera spoofing the Railway Guide (trains were to remain an obsession throughout his life—his diary is filled with loving descriptions of railway journeys to and from Oxford).

After a few unhappy years at Rugby School, during which he was hazed and bullied,[8] Carroll enrolled at Christ Church, Oxford in January 1851. There amid the parapets, pinnacles and crenellated towers of the “city of dreaming spires” he pursued a rigorous course of study, which placed him at odds with his fellow students who were more keen on partying than learning. (Thefts and vandalism were common; Cohen informs us that a group of young men once engineered an explosion that left a ravine running through the Christ Church quadrangle.) Carroll distinguished himself in mathematics and was ultimately nominated for a studentship (the Christ Church equivalent of a Fellow). Under the rules in place at the time, being a student enabled him to continue living and pursuing research at the college indefinitely—for the rest of his life, if he so chose. He was under no obligation to teach, though he elected to lecture and tutor. There were, however, two conditions: he must take holy orders (he later became a deacon), and he must remain unmarried.

Stipulations aside, Carroll’s situation would seem to have been—for those of a certain disposition—idyllic. Permanent room and board at Oxford, possibly the most romantic city in England. A lifetime of study. Some of us dream of such things. Certainly Carroll seems to have gloried in his good fortune, though he found the lecturing and tutoring taxing. “Today,” he wrote in 1855, “I … began a plan I hope to carry through—looking over all the Library regularly, to acquaint myself generally with its contents, and to note such books as seem worth studying.”[9] Much of his diary is devoted to recording the books he was reading at a given moment (North and South, Little Dorrit), along with the growing number of social engagements he enjoyed as he became fully settled at Christ Church.

Carroll began to acquire a reputation around Oxford, one that was not always positive. In the accounts given by his contemporaries one senses a certain befuddlement: no one quite knew what to make of this disarmingly handsome man (in photographs he resembles a young Gene Wilder) who shunned sports and hunting, published nonsense verse and seemed more at home in the company of children than their parents. There were some striking similarities between Carroll and that other great writer of stories for children, Hans Christian Andersen: both averse to conventional expressions of masculinity, both known to weep at odd moments (Carroll once broke down while reading a poem aloud)[10], both (we can infer from hints in their diaries) prone to ill-advised romantic attachments.

Yet while Andersen’s social oddities could be off-putting—his friendship with Dickens famously ended after he spent five weeks at Dickens’s home—Carroll seems largely to have attracted warmth and respect. His eccentricities were tolerable, even wholesome[11]. He once sent the gift of a pen-knife to a “child-friend” (as he called them) to be wielded against her brothers (Carroll heartily disliked boys, a disdain that emerges in the Alice books in the episode where a baby boy is transformed into a pig). Martin Gardner, in his indispensable The Annotated Alice, lists some of Carroll’s many inventions: music-boxes that could be played backwards; letters that began with the last word and ended with the first, and thus had to be read in reverse order; a game that was a sort of combination of chess and Scrabble, with letters instead of pieces. “Carroll’s rooms,” he tells us, “contained a variety of toys for the amusement of his child-guests,” among them “dolls, windup animals (including a walking bear and one called ‘Bob the Bat,’ which flew around the room), games, an ‘American orguinette’ that played when you cranked a strip of punched paper through it.”[12] A longtime insomniac, the riddles and brain-teasers he devised to induce sleep have been compiled by Gyles Brandreth into the book Lewis Carroll’s Guide for Insomniacs, in which Carroll explains the proper etiquette for greeting a ghost: “When encountering a ghost for the first time it is necessary to remain as calm as may be and to retain the normal courtesies of civilised society … on meeting a ghost in the street after dark a gentleman should always raise his hat.”[13] His advice reads like a droll send-up of the etiquette books that were then in fashion. Carroll’s genius lay in his fondness for taking the rituals and institutions of Victorian society and inverting, or distorting, them, as in a funhouse mirror—and never to greater effect than in the two books for which he’s today most famous, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

* * *

My earliest memories of Alice involve reading the book indoors on languid summer days, puzzling over the story with the same confusion it must have induced in Carroll’s peers. Unlike many fantasies today, with their excessive focus on realism in worldbuilding, Wonderland invites questions but makes no hurry to answer them. This is one of its great strengths. During Alice’s long fall down the rabbit-hole, who was it that placed the “cupboards and book-shelves,” the maps and paintings, the jars of orange marmalade, along the walls of the tunnel?[14] Who designed the “long, low hall … lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof,” the row of small doors hidden behind curtains and opening into cool, green gardens, that Alice finds when she lands with a thump, thump! at the bottom of the tunnel? We are never told. Wonderland must have door-makers and seamstresses and architects, but we never meet them.

Indeed, Carroll gives us just enough information about Wonderland, its landscape and citizens, to whet the appetite; but its history, its builders, its boundaries, its purpose, are never explained. And perhaps it’s this that still induces shivers when I read of Alice’s arrival in the low hall, no matter how often I’ve read the book. For by giving us so little, Carroll manages to make Wonderland seem eternal, infinite. During her conversation with the Cheshire Cat, Alice asks for directions out of the wood, which leads to this exchange:

“‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

“‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

“‘I don’t much care where—’ said Alice.

“‘Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

“‘—so long as I get somewhere,’ Alice added as an explanation.

“‘Oh, you’re sure to do that,’ said the Cat, ‘if you only walk long enough.’”

The Cat goes on to explain that in one direction lives a Hatter, and in another a March Hare. The topography of Wonderland is so convincingly depicted that, reading the books as a child, I believed—and I believe still—that Alice might have ventured off in any direction and seen any number of other strange places and creatures. They’re lurking, just at the edges of the page, around the next corner. The only reason we don’t meet them is because Carroll elected not to write about them.

And that sense of the million untold stories about Wonderland contributes both to the mystique of the book, and also the subtle current of horror running through it. Not all the creatures Alice meets on her journey are friendly. I loved the Cheshire Cat as a child (and still do) because he satisfied the desire all pet-lovers have for an ability to communicate with their pets. I loved him because he was evasive and enigmatic but also, I must admit, because he was a little scary. “The Cat only grinned when it saw Alice. It looked good-natured, she thought: still it had very long claws and a great many teeth, so she felt that it ought to be treated with respect.” The Cat could easily devour Alice if it wished. Carroll doesn’t stress the point, but the threat is there.

The implicit threat of death, in fact, runs through both the Alice books. The Duchess and the Queen of Hearts are fond of demanding beheadings. Alice is made to recite a poem about an owl and a panther that ends, it is strongly hinted, by one eating the other. The narrator makes stealth jokes about Alice’s death, as does Humpty Dumpty: when Alice gives her age in the second book as seven and a half, he replies, “With proper assistance, you might have left off at seven.” (As Martin Gardner notes, “No wonder that Alice, quick to catch an implication, changes the subject.”[15])

Parents, both then and now, have objected to the violence in the Alice books, as they do the violence in the Grimm Brothers’ fairy-tales. For kids, the violence is thrillingly transgressive… and persuasive. For those who have grown up in broken homes, those who have been bullied at school, who have known a loved one murdered, Wonderland resonates because it depicts life. “He wove fear, condescension, rejection, and violence into the tales,” Cohen notes, “and the children who read them feel their hearts beat faster and their skin tingle, not so much with excitement as with an uncanny recognition of themselves, of the hurdles they have confronted and had to overcome.”[16] Carroll never condescends. Nearly everyone Alice meets is unpleasant, rude and easily offended; several are frankly abusive. This is, I’ve often thought, the difference between a good children’s book and a bad one. The bad books sugarcoat life; they paint adults as unrealistically inspirational and caring.[17] The good ones understand that adults are murderous (at worst) and well-intentioned but useless (at best). Accurate or not, this is how children see adults; and the writers who haven’t yet forgotten what it was like to be a child know this. Carroll did, for a time.

* * *

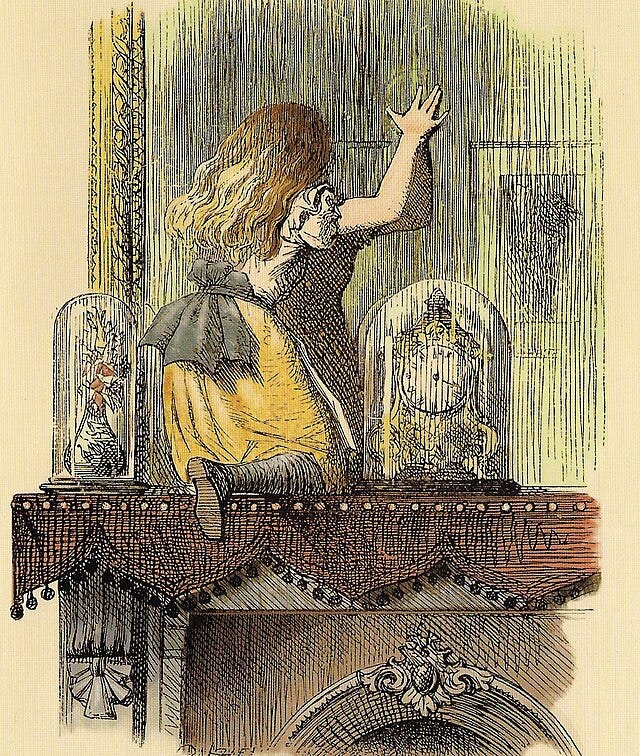

There is a moment early in Through the Looking-Glass that for sheer originality and comic inventiveness is probably unrivalled in literature.

In this second book, set six months after the first, Alice falls asleep on the eve of Bonfire Night (in early November) and dreams that she’s traveled through a mirror in her room into Looking-Glass World. The country outside the house resembles a vast chess board, with “a number of tiny little brooks running straight across it from side to side, and the ground between … divided up into squares by a number of little green hedges.” Each time Alice crosses one of the brooks to the next square, she finds herself transported at once to a new location. The Red Queen explains to her that once she reaches the opposite end of the board, like a pawn in a real game of chess, she’ll become a queen.

The prospect of becoming a queen greatly appeals to Alice; so, taking her leave of the Queen, she descends a hill and crosses the first of six brooks. In the next instant…

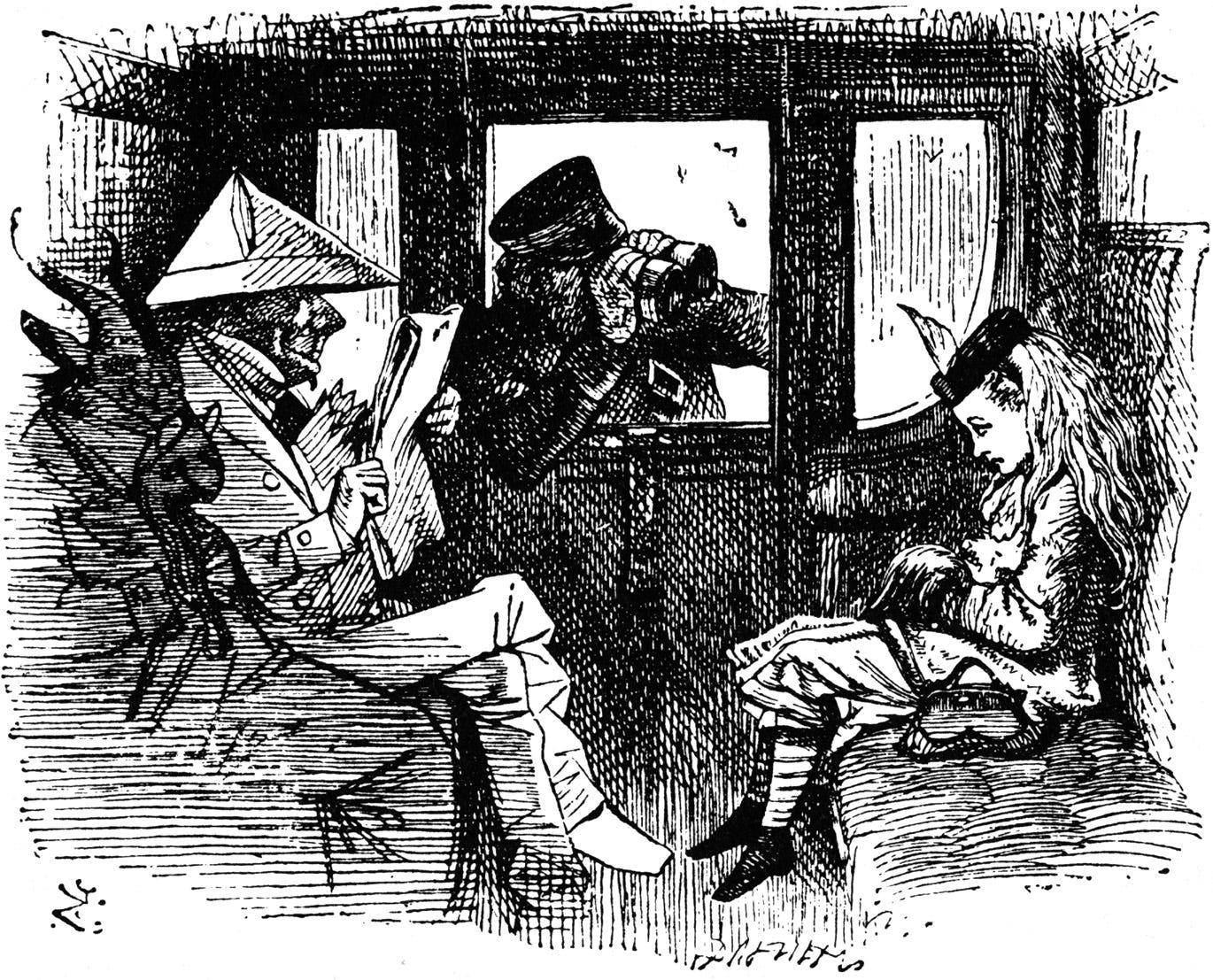

“‘Tickets, please!’ said the Guard, putting his head in at the window. In a moment everybody was holding out a ticket: they were about the same size as the people, and quite seemed to fill the carriage.”

A reader could be forgiven, on reading the book for the first time, for wondering if perhaps some pages were missing from her copy. Alice had been quite alone a moment before… and now suddenly a crowd? A train?

“‘Now then! Show your ticket, child!’ the Guard went on, looking angrily at Alice. And a great many voices all said together (‘like the chorus of a song,’ thought Alice) ‘Don’t keep him waiting, child! Why, his time is worth a thousand pounds a minute!’”

This goes on for some time, with all the occupants of the carriage speaking in chorus (and, when Alice thinks, ‘There’s no use in speaking,’ everyone thinking in chorus). The Guard gazes at her “first through a telescope, then through a microscope, and then through an opera-glass,” before tersely informing her, “You’re traveling the wrong way” and shutting the window. Alice finds herself seated opposite a goat, a beetle, a gentleman in a white hat who resembles Benjamin Disraeli, a melancholy gnat who calls himself “an old friend, and a dear one,” and apparently an infinite number of other creatures, unseen, who offer commentary (“She ought to know her way to the ticket-office, even if she doesn’t know her alphabet!” says the Goat).

Of course this is all quite funny; but even more, it’s bizarre. There seems to be no precedent for this sequence of events in any previous literature, nothing that could be credited as an inspiration. Some fantasy writers—C. S. Lewis was one of them—have a kind of genius for borrowing plots and ideas from previous writers. Lewis Carroll was borrowing from no one. If you read the early novels of Dickens (especially The Old Curiosity Shop), you can see hints of the whimsy and eccentric characterization that would become Carroll’s trademark; but no one before Carroll had written such fluid narratives, in which chronology and causation are casually discarded, in which a queen becomes a sheep and a shop becomes a river, in which puddings protest being sliced and goats’ beards melt away on being touched, in which memories run forwards and bottles take flight and candles rise like rockets.

“It’s almost impossible to overstate what strange books Alice’s Adventures and its sequel are,” says Sam Leith. This is doubly true of Through the Looking-Glass, which far exceeds the first book in the sharpness of its jokes, in the surrealism of its dream-landscapes, in the sudden tonal shifts from broad comedy to adult melancholy (Carroll is clearly haunted in this book by the ephemeral nature of childhood and the real Alice’s rapid progress towards maturity).[18] The Alice books were foundational to the counterculture of the late 1960s, and indeed one could argue that Carroll was the true father of the psychedelic era. John Lennon seems to have owed much of his personality to repeated boyhood readings of Looking-Glass, and there are nods to the book scattered throughout the Beatles’ best album, Sgt. Peppers’ Lonely Hearts Club Band—not just the overt allusions to “cellophane flowers” and waltzing horses, but the dreamy manner in which the album progresses through a variety of shifting scenes and moods, mirroring Alice’s journey through woods and along rivers, both works culminating in someone waking from a dream.

* * *

I’ll never forget an incident that took place in the sixth grade.

I was seated against the bleachers during gym. It had been raining all morning and we were having one of those occasional free periods where we could amuse ourselves however we liked, so most kids clustered in groups cross-legged on the cool floor to chat with their friends. Gary, who happened to be sitting a few feet away, glanced over and asked what I was reading.

“Alice in Wonderland,” I said, slightly vexed at having been interrupted. Since discovering the book the previous year, I’d read it close to a dozen times.

I’d grown used to being harassed for my reading choices: a number of kids had made fun of me for reading Rebecca in the fifth grade because it looked like a romance novel. But it was still shocking to see Gary turn to his friends with a shrug and a smirk and say, “Baby book.”

It’s unseemly, I know, to be carrying a grudge over this more than twenty-five years later; but Gary’s prejudice is sadly still too common, even among adults who should know better. Carroll’s books were written at a time when there was no hard distinction between books for children and books for adults, and thus he was writing for both audiences. Christina Rossetti and her brother, the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, numbered among his legions of fans. Alice was foundational for the generation of English novelists who came of age between the wars: Anthony Powell and Evelyn Waugh wrote satirical novels that can fairly be described as Alice minus the talking critters[19]. Philosopher and mystic Alan Watts dubbed Alice a “Zen textbook.” Harold Bloom, scornful of Harry Potter and other recent children’s fantasies, described Carroll as “Shakespearean” and his books “a kind of scripture,” hailing him as “so original that he transmutes every possible source into alchemical gold instantly recognizable as unique to him.”[20]

Roger Ebert, in a review of the film Amadeus, makes a useful distinction between merely talented artists and artists of genius. Nearly-great artists labor and strain to produce great works; great artists make their work seem like play. Geniuses, he writes, “rarely take their own work seriously, because it comes so easily for them.”[21] Reading Carroll’s diaries, one is struck by just how little he mentions Alice between its inception on that July outing and its publication a few years later. In August 1865 he expressed the hope that Alice might sell 4,000 copies. By the end of the century it had sold close to a quarter million. First printings sold at auction fetch between two and three million pounds. In the space of a few months in the summer of 1862 Carroll had scribbled down one of the world’s most lucrative intellectual properties—and he had no idea.

So there is a genius to the Alice books, one that’s more readily recognized by adults than by children. “There’s a strong case to be made,” says Leith, “that they aren’t really—or aren’t primarily—even children’s books at all.” Today, while the story remains culturally ubiquitous through its many adaptations,[22] the books’ most ardent admirers tend to be philosophers, scientists, linguists, mathematicians—precisely the sort of people who can best appreciate the cleverness of Carroll’s exercises in logic and illogic. Gardner devotes many pages in The Annotated Alice to pointing out the various layers of meaning lurking just under the surface of the books, and their applications to such fields as relativity, metaphysics and quantum physics. Alice questions whether milk from a looking-glass world would be safe to drink, inadvertently anticipating by some years the discovery that “organic substances had an asymmetric arrangement of atoms” and that the consumption of reversed food or drink would likely have unpleasant effects on the body.[23] Alice walks through a wood where creatures forget their own names, and is later informed by Humpty Dumpty that he can make a word mean anything he pleases; in both sequences Carroll nods to the fact that all words and labels are human inventions and “the world by itself contains no signs”—“by no means a trivial philosophic insight,” as Gardner notes.[24]

When Alice is chatting with Tweedledum and Tweedledee, just after they’ve recited “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” she hears a tremendous noise like a steam-engine in the woods. On inquiring whether there are any beasts in the woods:

“‘It’s only the Red King snoring,’ said Tweedledee.

“‘Come and look at him!’ the brothers cried, and they each took one of Alice’s hands, and led her up to where the King was sleeping.

“‘Isn’t he a lovely sight?’ said Tweedledum.

“Alice couldn’t honestly say that he was. He had a tall red night-cap on, with a tassel, and he was lying crumpled up into a sort of untidy heap, and snoring loud—‘fit to snore his head off!’ as Tweedledum remarked…

“‘He’s dreaming now,’ said Tweedledee: ‘and what do you think he’s dreaming about?’

Alice said ‘Nobody can guess that.’

“‘Why, about you!’ Tweedledee exclaimed, clapping his hands triumphantly. ‘And if he left off dreaming about you, where do you suppose you’d be?’

“‘Where I am now, of course,’ said Alice.

“‘Not you!’ Tweedledee retorted contemptuously. ‘You’d be nowhere. Why, you’re only a sort of thing in his dream!’

“‘If that there King was to wake,’ added Tweedledum, ‘you’d go out—bang!—just like a candle!’”

Alice and the Tweedle Brothers continue to argue over the question of whether she’s a real person or just a “sort of thing in his dream,” an argument that ends in tears for poor Alice. When she notes, “If I wasn’t real, I shouldn’t be able to cry,” Tweedledum replies, “I hope you don’t suppose those are real tears?” The sequence gestures at eighteenth-century philosopher George Berkeley’s theory of “immaterialism,” which held that the material world only exists when perceived by a mind—or, put another way, that we’re only characters in a dream God is having.

These are deep waters. Setting aside the philosophical conundrum exposed by the two brothers, the passage hints at a thread of existential fear running through both Alice books, the fear of ceasing to exist. The imagery hearkens back to a scene in the previous book, when Alice wonders how it would feel to shrink down into nothing: “for it might end, you know … in my going out altogether, like a candle. I wonder what I should be like then?” Later she touches a white kid-glove worn by the Rabbit that causes her to shrink rapidly. She only realizes the danger, and tosses away the glove, just moments before she would have disappeared altogether. “‘That was a narrow escape!’ said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence.” There are enough such passages in Alice (and in Carroll’s magnificent nonsense poem, The Hunting of the Snark) to suggest that the outwardly pious reverend was plagued by private doubts.

But I think that fear of being nowhere, of going out like a candle, is linked with another anxiety that shadows the pages of the two books, of Looking-Glass especially. It’s the awareness that people—children, especially—are constantly changing, and that I may not be the same person I was when I woke this morning. In the low hall, disoriented, Alice fears she’s been transformed into some other child of her acquaintance, perhaps Ada or Mabel: “But if I’m not the same, the next question is ‘Who in the world am I?’” After shrinking and growing a number of times, and being branded a “serpent” by a pigeon, Alice says, “How puzzling all these changes are! I’m never sure what I’m going to be from one moment to another!” But of course this is precisely how the experience of physical maturation feels to a child: Alice’s transformations only mirror, in exaggerated form, the changes undergone by the body as it develops, changes that are often as confusing and frightening for real children as they are for Alice.

There’s a moment in chapter five of Through the Looking-Glass, “Wool and Water”—my favorite chapter in literature—that condenses, into a single image, all the hidden fears and despairs running through the book. Crossing a little brook alongside the White Queen, Alice finds herself in a dark shop. The Queen is seated at the counter, furiously knitting; only she’s no longer a queen, but an old sheep. Alice attempts to make several purchases, but whenever she looks directly at a shelf, she finds it empty. Before long the Sheep’s needles have become oars and the two of them are gliding down the river in a small boat; as the boat drifts, Alice amuses herself by attempting to gather some scented rushes that are clustered on the surface of the water.

“‘I only hope the boat won’t tipple over!’ she said to herself. ‘Oh, what a lovely one! Only I couldn’t quite reach it.’ And it certainly did seem a little provoking (‘almost as if it happened on purpose,’ she thought) that, though she managed to pick plenty of beautiful rushes as the boat glided by, there was always a more lovely one that she couldn’t reach…

“What mattered it to her just then that the rushes had begun to fade, and to lose all their scent and beauty, from the very moment that she picked them? Even real scented rushes, you know, last only a very little while—and these, being dream-rushes, melted away almost like snow, as they lay in heaps at her feet.”

Carroll may have had in mind Prospero’s valedictory speech in Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest: “… the solemn temples, the great globe itself / Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve … We are such stuff as dreams are made on / And our little life is rounded with a sleep.” This is the unhappy truth at the heart of the Alice books: that childhood, youth—we ourselves—are as insubstantial as a smile. We’re here for a moment, and already the moment begins to fade in the act of being perceived. To be in one’s thirties, as Carroll was when he wrote the above passage, is to be aware that the span of our lives is not long.

Nothing lasts—except, perhaps, the yearning for something that can’t be reached. While Carroll’s later years brought global fame and renown, they also brought frustration and disappointment. Several of his child-friends abruptly severed ties when they were grown. Changing mores brought increased scrutiny to the nature of those friendships, and renewed whispers. At some point, too, Carroll’s genius seems to have deserted him. His final books for children, Sylvie and Bruno (1889) and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893), lack the casual, tossed-off air of the Alice books. They exhibit a sentimental view of children as unsullied innocents that’s at odds with any real-world experience of children, and a strain of evangelical fervor at odds with the cheerful anarchy of his earlier books. “Something,” writes Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, “has badly corroded Carroll’s intelligence. The more urgently he tries to get back in contact with his original storytelling mood, the further away he proves to have drifted.”[25] Like many who would come after him, Carroll fundamentally misunderstood the appeal of the books. It never occurred to him that prickly, stubborn Alice is the antithesis of pompous sentiment and pious moralizing—the antithesis, in short, of the books he was now writing. Carroll had grown in the wrong direction, and been ejected from Wonderland.

If only there were some way to get back. Anticipating H. G. Wells by several years, midway through Sylvie and Bruno Carroll introduces a “magic watch” with the power to reverse time when its hands are turned back. “What a blessing such a watch would be!” says the narrator, “in real life! To be able to unsay some heedless word—to undo some reckless deed!”[26]

Reading this now, one can’t help but wonder what regrets Carroll harbored as he neared the end of his life. In her old age, Alice Hargreaves (née Liddell) occasionally expressed irritation at having to play the public role into which she had been permanently confined; she wrote to her son Caryl, “oh, my dear I am tired of being Alice in Wonderland! Doesn’t it sound ungrateful & is—only I do get tired.”[27] As pleased as she was to be associated with Carroll, the association had also, in some sense, broken her. For her, as for him, the invention of Wonderland during those long-ago summer trips to Godstow and Nuneham had proven the decisive event in their lives. Sensing the uniqueness of the story, Alice had urged him to write it down. After much pestering, he had done so; and the world was changed. But it’s hard not to escape the feeling that, for Carroll at least, his life had reached a shining perfection in those river outings; and that after, he was never as happy again.

[1] The Diaries of Lewis Carroll, Vol. 01, ed. Green, Roger Lancelyn. Oxford University Press, 1954.

[2] Cohen, Morton N. Lewis Carroll: A Biography. Vintage Books, 1995.

[3] Carroll, Lewis. The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition, ed. Martin Gardner. 1995.

[4] Rundell, Katherine. “Why Children’s Books.” London Review of Books. February 6, 2025. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v47/n02/katherine-rundell/why-children-s-books

[5] Sturrock, Donald. Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl. Simon & Schuster, 2010.

[6] Cohen, Lewis Carroll.

[7] Woolf, Jenny. The Mystery of Lewis Carroll: Discovering the Whimsical, Thoughtful, and Sometimes Lonely Man Who Created Alice in Wonderland. St. Martin’s Press, 2010.

[8] Rugby continues to inspire ill feeling. In 2011 Salman Rushdie said, “Almost the only thing I am proud of about going to Rugby School was that Lewis Carroll went there too.”

[9] The Diaries of Lewis Carroll, volume 01. March 12, 1855.

[10] Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland. Harvard University Press, 2015.

[11] As for the recent accusation that Carroll was a “pedophile” because he took photographs of nude children, the only thing that can be said is that it didn’t strike the people of his own age as being an unusual hobby. “Child nudes were a wholly conventional Victorian interest,” Sam Leith tells us in The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading. “They even appeared on Christmas cards.” There were rumors circulating in Oxford at the time that he had proposed to one of his child-friends, but this was also regrettably common: Carroll’s brother Wilfred proposed to a girl of fourteen (also named Alice), and Carroll persuaded him to desist until she was fully grown. It’s worth noting that in her old age Alice Liddell had only glowing things to say of him.

[12] Gardner, The Annotated Alice.

[13] Gyles Brandreth, Lewis Carroll’s Guide for Insomniacs. Notting Hill Editions, 2024.

[14] Kurt Vonnegut, in Pity the Reader: On Writing with Style, singles out this sequence as an example of Carroll’s narrative genius: “Give your readers familiar props along the way. In Alice in Wonderland, remember, when she's falling down the hole there are all these familiar, comforting objects along the sides.”

[15] Gardner, The Annotated Alice.

[16] Cohen, Lewis Carroll: A Biography.

[17] This is why I’m vexed when that line from the 2010 movie is wrongly attributed to Carroll: “You’re entirely bonkers. But I’ll tell you a secret: all the best people are.” The Cheshire Cat would never say this. Carroll would never write it.

[18] Champions of the second book over the first are a minority, but a vocal one. “The second Alice book has a visionary otherness that I cannot locate in the first,” writes Harold Bloom in Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Minds. “There seems to me both aesthetic gain in sophistication, and aesthetic loss in exuberance, as you read on from one book to the other.”

[19] Carpenter, Humphrey. The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh & His Friends. Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

[20] Bloom, Harold. Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Minds. Warner Books, 2002.

[21] Ebert, Roger. Amadeus. April 14, 2002. Rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-amadeus-1984.

[22] Alice is notoriously unfilmable, and the only screen versions to have approached the magic of the books are both animations: a 1981 Russian film and Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001), not a direct adaptation but an original story in the spirit of Carroll. The latter is one of the century’s great films. Also worth mentioning is the 1966 British television play Alice in Wonderland, filmed in Oxford and featuring a gleefully unbalanced performance by Peter Cook as the Mad Hatter.

[23] Gardner, The Annotated Alice.

[24] Carroll has more fun with this concept during Alice’s encounter with the White Knight, in which Alice and the Knight bicker over the difference between a song’s name and what the song’s name is called.

[25] Douglas-Fairhurst, The Story of Alice.

[26] Carroll, Lewis. Sylvie and Bruno. MacMillan & Co., 1889.

[27] Douglas-Fairhurst, The Story of Alice.

What a tribute to Carroll and his Alice/Wonderland books!

I learned so much about the world that inspired the books, and about the wonderful and complex man who wrote them.

Cohen's observation captures so much: “He wove fear, condescension, rejection, and violence into the tales, and the children who read them feel their hearts beat faster and their skin tingle, not so much with excitement as with an uncanny recognition of themselves, of the hurdles they have confronted and had to overcome.”

Thanks for this marvelous essay, Boze!

My favorite scene from LOOKING-GLASS has always been that brief interlude with the fawn in Chapter 3. It is heartwarming, tragic, and thought-provoking by turns.