The Shadow Canon 03: Moby-Dick & the Book of Job

The Mystery of Suffering and a Hostile Universe

[A brief bit of housekeeping: Having just finished reading Plato’s Timaeus, while I found it delightful, I don’t feel remotely qualified to blog about it. So—unless someone else would like to write a guest post?—I think we’ll remove it from our syllabus and add Elspeth Barker’s novella O Caledonia, which I also read recently and loved. We’ll read it after Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Gate of Angels.]

As William Aetheling prepared to set sail from Normandy on the night of November 25, 1120, there was nothing in the sea or the skies to suggest that this would be anything other than an ordinary Channel crossing.

William was sixteen years old, the son of King Henry I and heir apparent to the throne of England (that’s why he was called “Aetheling”). William of Malmesbury and Orderic Vitalis, who wrote two of our seven accounts of that night, were not overly fond of William. He was boisterous and spoiled, with a prince’s sense of entitlement, the twelfth-century equivalent of a senator’s son who joins a fraternity during his first semester at Yale and spends his weekends in boozing and revels.

As the White Ship prepared to embark that night, great casks of wine were rolled along the gangplanks onto the deck. Two hundred and fifty young men and women—the flower of Norman nobility—huddled together against the cold air, their heavy gowns of bright colors plainly visible from the Barfleur quayside. Among them stood a man clad in a simple woolen coat, a butcher from Rouen named Berold who had boarded the ship in the hopes of collecting some money he was owed. He may have been the only person aboard who wasn’t drinking.

It had been a tumultuous couple decades for the royal family. William I had been succeeded in 1087 by his son, William Rufus, but by the summer of 1100 William Rufus was dead as well, the victim of a stray arrow during a stag hunt in the New Forest. His brother Henry, with admirable swiftness, had summarily seized the treasury and declared himself king. That had been twenty years ago. Since then King Henry had sired numerous offspring with his various mistresses but only one legitimate heir, William, now the hope of the nation. By an odd coincidence, the White Ship’s captain, Thomas FitzStephen, was the son of the man who had captained William’s grandfather on the fateful Channel crossing that made him conqueror and king of England in 1066.

One can’t help wondering what William was thinking that night as he gazed out over the untroubled waters. Two of his half-siblings had accompanied him on the ship, a sister, Matilda, and a brother, Richard. They were briefly joined by William’s older cousin, Stephen, Count of Blois and nephew of King Henry and a man known for his generous nature. Stephen disembarked early, complaining of an upset stomach (some accounts say diarrhea), though it’s likely that the spectacle of passengers and crewmen engaging in drunken antics unnerved him. Seizing on a pretext, he returned to shore.

Playing up the connection with William the Conqueror, FitzStephen had approached Henry wanting to know if the king would like to employ the ship on his trip home from the continent. Henry declined—he had already arranged to travel aboard another ship, a dragon-headed longship known as an esnecca from the Scandinavian word for serpent—but agreed to grant William and his retinue use of the ship. The esnecca sailed from port early that evening, but the White Ship remained docked for some hours as passengers and crew drank and made merry with growing zeal. “When priests arrived to bless the vessel with holy water before her departure,” Dan Jones tells us in his book The Plantagenets, “they were waved away with jeers and spirited laughter.”[1]

The journey, writes Helen Castor, “was not to be taken lightly, especially in winter, when the risk of rough winds and towering waves made the journey particularly hazardous. Henry himself had never before sailed later in the year than September, but there seemed no cause for concern as he surveyed the glassy water, scarcely rippled by the southerly breeze that would billow gently in the ships’ sails on the way north to the English coast.”[2] Aboard the White Ship, however, the captain and his foolhardly crew were beginning to wonder if they could beat the esnecca back to Southampton. FitzStephen’s ship bore fifty skilled oarsmen capable of rowing at great speed in calm waters with no winds in its sails.[3] The design of Henry’s ship made it one of the fastest in England; what a wonderful thing, then, what extraordinary cause for boasting, if the White Ship, after a delay of several hours, should overtake the king himself and succeed in reaching England before him!

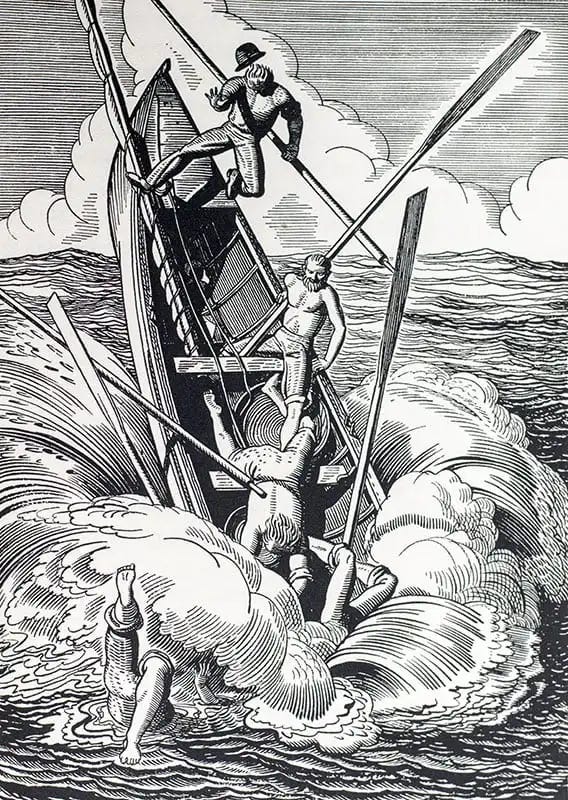

Cheered on by the drunken courtiers who crowded the upper deck, FitzStephen ordered his (equally inebriated) oarsmen to row at full speed in the direction of the distant ship. As midnight approached, the cool air frosted; a new moon left the churning waters in near-total darkness. Approximately one mile from shore, and still visible from the dock whence they had just sailed, lay the Quillebouef Rock, a treacherous outcrop. There was an agonizing noise of splintering wood as the hull of the White Ship ground against the rock. With merciless efficiency the ship began to take in water. The screams of the young nobles could be heard in the streets of Barfleur.

Displaying remarkable presence of mind, some of Prince William’s men flung him into a small boat. Even in that moment of direst emergency, the life of the aetheling took precedence. Assisted by oarsmen, he and several others began making their way to shore. It’s likely that he would have survived—except that, behind him, he heard the desperate screams of his sister, Matilda. She, like many of the elite passengers, now struggled to rid herself of the enormous gown she had worn onto the ship. Thoroughly soaked, it was dragging her down into the cold sea. William screamed at the oarsmen to reverse course. Reaching out his hands, he pulled her into the boat. But some of the dozens of other passengers, glimpsing salvation, began scrambling in William’s direction and attempted to climb aboard. The fragile vessel couldn’t hold their weight. Within moments it had capsized, sending Matilda, William and everyone else aboard to their deaths.

Two hundred and fifty people died that night. It was said that when Captain FitzStephens learned of William’s death, he drowned himself rather than return to England and face the wrath of King Henry. It took several days for the news to reach the king, now safely arrived in Southampton. Jones writes: “Magnates and officials alike were terrified at the thought of telling the king that three of his children, including his beloved heir, were what William of Malmesbury called ‘food for the monsters of the deep.’ Eventually a small boy was sent to Henry to deliver the news; he threw himself before the king’s feet and wept as he recounted the tragic news. According to Orderic Vitalis, Henry ‘fell to the ground, overcome with anguish.’ It was said that he never smiled again.”

The sinking would prove a disaster in other ways. After William’s death, Henry insisted to whomever would listen that his daughter, Matilda, would be his heir. However, when Henry died in the autumn of 1135, Stephen, the man who had bailed from the ship that night claiming an upset stomach, declared himself king. Matilda and Stephen would spend much of the next decade fighting a brutal civil war that became known as the Anarchy, when, it was said, “Christ and His saints slept.”[4]

One person survived the shipwreck, which is how we know so much of what transpired aboard the White Ship on that cold night. On the following morning, when a rescue party from Barfleur set out to survey the wreckage, they found, clad in woolskin and clinging to bare rock, Berold, the butcher of Rouen.

* * *

“And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.”[5] They are some of the last words spoken in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a book that is at once seafaring tale, revenge quest, encyclopedia, poem, and postmodern meditation on fate, free will, and the nature of evil, and which ends (spoiler alert for a 170-year-old book) with almost its entire cast dead, and its narrator, like Berold, adrift alone on the open sea awaiting rescue.

If you’ve never read Moby-Dick, let me warn you upfront to disregard whatever bad things you may have heard about it. This is a novel with a reputation, and that reputation has not always been positive. People say it’s “boring,” that the whaling chapters are “a slog,” that the language is difficult and strange. Ignore them. I’m here to tell you that it’s worth reading. More than that, it’s the greatest work of fiction ever written by an American author, a book that is shockingly contemporary in its experiments with form and technique (some scenes are written like a play; there’s a moment where Melville pauses the story to tell you the precise minute and date on which he’s writing the current chapter). And the subjects it tackles—marriage, madness, money, queer love, geology, tyranny, race relations, religious tolerance, depression, and the indifference bordering on hostility of a beautiful but mysterious universe—give the book a scope that is almost unparalleled in world literature. There are depths here as deep as the lowest soundings of the sea. Moby-Dick is a grand book.

But don’t take my word for it. Like the night sky, like the sea itself, Melville’s epic has a habit of inducing raptures. In his Nobel lecture, Bob Dylan described the book’s hodgepodge nature as an influence on his own approach to songwriting: “Everything is mixed in. All the myths: the Judeo-Christian Bible, Hindu myths, British legends, St. George, Perseus, Hercules … Greek mythology, the gory business of cutting up a whale … everything thrown in and hardly none of it rational.” Branding it “the nation’s epic,” journalist Stephen Kinzer calls Moby-Dick “an eerily prophetic allegory about 21st-century America.”[6] Jungian analyst Edward Edinger, writing in 1995, thought it a modern myth.[7] “Contained in the pages of Moby-Dick,” writes historian Nathaniel Philbrick, “is nothing less than the genetic code of America.” It’s “the one book,” he adds, “that deserves to be called our American Bible.”[8] Both Hemingway and Faulkner expressed jealousy at Melville for having written it. Ray Bradbury, who fell in love with the book while writing the screenplay for a film adaptation, called Shakespeare and Melville “children of the gods.” Annie Dillard dubbed it “the best book ever written about nature.”

They’re correct, all of them. But what I find fascinating about Moby-Dick, what keeps me coming back year after year, is Melville’s engagement with the big questions. How does one manage life under a deranged leader driven by his own inexorable agenda? What is the nature and role of God in a world of natural selection?[9] Who are we in the face of those “heartless immensities” of deep space and deep time? Some of these are questions that people were only beginning to ask in Melville’s era. Some are older than the Bible, as old as the written word—and perhaps older.

As the story begins, our narrator (“Call me Ishmael”) is feeling restless. It is a “damp, drizzly November” in his soul. Heading to New Bedford, he resolves to book passage on the Pequod, a whaling vessel. After booking a room at a local inn, he’s reluctantly coaxed into sharing a bed with a brawny South Sea cannibal and harpooner named Queequeg. Initially, Ishmael is not a fan of his new bedmate; but after spending an evening with him, he finds his heart opening up to the tattooed islander: “Thus, then, in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queequeg—a cosy, loving pair.”[10]

Ishmael is warned by a mysterious figure named Elijah not to board the Pequod. Strange stories are circulating about the ship and its captain, Ahab. It’s said that he walks with a wooden leg following a near-fatal encounter with a ferocious sea beast, a gargantuan albino whale. Ignoring the many warnings, Ishmael and Queequeg board the ship. They set sail on Christmas Day from Nantucket.

For many days there’s no sign of the captain above deck. Then Ahab appears—and this is where things begin to get really strange. (You can almost pinpoint the moment when Melville, up to now a bestselling novelist of exciting travel yarns, became obsessed with Paradise Lost and the tragedies of William Shakespeare.) Nothing on the ship, or in the book, behaves normally. Ahab delivers a monologue to himself which no one could have heard, raising the question of how Ishmael is able to tell us about it. He’s revealed to have been hiding five turbaned men below deck, who operate as a sort of shadow crew; one of the men is implied to be the devil. Ahab then discloses the secret purpose of the voyage, to hunt and destroy the whale that ate his leg, and the entire crew falls under his sway as though entranced. And Ishmael, or Melville, begins grappling with the mystery at the heart of the book: why do bad things happen? Why does the universe seem hostile, or at best indifferent, to the fate of mortals?

It soon becomes clear that the whale is more than just a whale for Ahab. He represents something cosmic. For him Moby Dick signifies the willful, malicious evil lurking at the heart of life. “All visible objects, man,” he says, “are but as pasteboard masks” hiding a sinister intelligence. Ahab hopes to strike at that intelligence, the God that he insanely blames for the loss of his leg and his forty-years’ separation from his wife. In a clever send-up of nineteenth-century Calvinism,[11] Ahab convinces himself that he has no free will. When his men beg him to stop this mad quest and return home, he replies that he can’t stop—because God Himself has doomed Ahab and the crew to destruction. “Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm?”[12]

Ishmael doesn’t share his captain’s blasphemous disdain for God (and it helps to keep in mind that Ahab, more so than the whale, is the book’s Luciferian antagonist). But amid the frenzied air of the ship, in the mesmeric thrall of a demagogue, he begins to question the nature of reality: of death, heaven, hell, eternity and time. Over the course of chapters 41 to 44 he ponders the psychology of Ahab, his motivations for pursuing “vengeance on a dumb brute,” and what the whale signifies to that mad mind, in a lengthy digression that crescendos in chapter 42, “The Whiteness of the Whale.” This chapter, all seven pages, is a shattering piece of writing, a Mount Kilimanjaro of literature, as horrifying as it is sublime.

Here Ishmael attempts to answer the question of why he found the whale’s whiteness so unsettling. There follows a long list of things in history, nature and religion that unnerve us with their spectral coloring (or lack of it)—the white robes of monks, the white throne of the day of judgment, and so forth. Like an attorney laying out an argument, he cites example after example to establish that the unconscious mind recoils from the sight of unspotted whiteness. And, just when you were beginning to suspect that Ishmael has lost the thread, he drops this banger of a line: “Though in many of its aspects this visible world seems formed in love, the invisible spheres were formed in fright.” As benevolent as the world might appear when you’re standing in a meadow on a spring day listening to birdsong, there is, Ishmael suggests, a sort of hidden horror lurking at its heart.

He explains what he means in the closing paragraph of the chapter. Still on the subject of whiteness, he writes:

“Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? … And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues—every stately or lovely emblazoning—the sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtle deceits, not actually inherent in substances, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within … pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper; and, like wilful travellers in Lapland, who refuse to wear colored and coloring glasses upon their eyes, so the wretched infidel gazes himself blind at the monumental white shroud that wraps all the prospect around him. And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol.”[13]

If you’re able to follow the thread of Ishmael’s argument, this closing statement can’t help but produce shivers. It’s the same argument that David Lynch was making in the opening shot of his movie Blue Velvet, when a camera hovering above a pristine suburban lawn suddenly descends below the topsoil to reveal the maggots festering beneath. Like Lynch, Melville is making a point about America, about the wolf of slavery and imperialism slouching behind the mask of our pieties. But he’s also making a point about the world into which we’re born, a world in which, as Joseph Heller put it, people are “shot to death in hold-ups, strangled to death in rapes, stabbed to death in saloons, bludgeoned to death with axes by parents or children…”[14] And, he might have added, frozen to death in snows, eaten by dogs, baked in heat, drowned in floods, sent to the bottom of the English Channel on a serene November night within sight of land. If the universe furnished our only clues to the nature of God, wrote C. S. Lewis, “I think we should have to conclude that He was a great artist (for the universe is a very beautiful place) but also that He is quite merciless and no friend to man (for the universe is a very dangerous and terrifying place).”[15] And here in chapter 42, the hostility and heartlessness of the universe evokes in Ishmael a kind of nihilism. He will not remain a nihilist, as we shall see; despair does not have the last word. But it makes a compelling case.

Melville, as history writer Nathaniel Philbrick reminds us, was haunted by the real-life sinking of the whale ship Essex, a disaster that provided the inspiration for the events of Moby-Dick. The Essex had sunk in the western Pacific after being rammed by a sperm whale, but twenty members of the crew survived the attack and set out for the coast of South America in whaleboats. (The Marquesas Islands were closer but they shunned those, having heard rumors of cannibalism.) Months later, when the five remaining sailors were discovered by a passing ship, they revealed that they had survived the ordeal by eating their fellow crewmen. Philbrick notes, “They had become what they most feared.”[16]

This is the context for one of the weirder moments in the novel, when the severed head of a recently captured sperm whale is hoisted alongside the Pequod and Ahab, emerging from his cabin, addresses the head like Hamlet addressing the skull of Yorick. Speculating on the horrors that the deceased whale might have witnessed, Ahab powerfully channels the fear that the sight of the sea evokes. “Speak, thou vast and venerable head,” he says:

“… which though ungarnished with a beard, yet here and there lookest hoary with mosses; speak, mighty head, and tell us the secret thing that is in thee. Of all divers, thou hast dived the deepest. That head upon which the upper sun now gleams, has moved amid this world’s foundations. Where unrecorded names and navies rust, and untold hopes and anchors rot; where in her murderous hold this frigate earth is ballasted with bones of millions of the drowned; there, in that awful water-land, there was thy most familiar home … Thou saw’st the locked lovers when leaping from their flaming ship; heart to heart they sank beneath the exulting wave; true to each other, when heaven seemed false to them. Thou saw’st the murdered mate when tossed by pirates from the midnight deck; for hours he fell into the deeper midnight of the insatiate maw; and his murderers still sailed on unharmed—while swift lightnings shivered the neighboring ship that would have borne a righteous husband to outstretched, longing arms. O head! thou hast seen enough to split the planets and make an infidel of Abraham, and not one syllable is thine!”[17]

Everyone who’s lived long enough has witnessed some inexplicable tragedy that challenged their notion of a just world. When I was twelve, I learned that my family was planning a trip to Disneyworld in Orlando during the summer. This puzzled me, as we didn’t have the money for an eight-day trip. My sister explained that a family friend, a man named Wilbur[18], had offered to take us. Wilbur had recently won millions of dollars in a lawsuit after his wife died in a freak accident. She had been out jogging with friends in Houston one morning when they decided to take a detour through the local mall. At the exact moment they entered the building, a 200-foot portion of the roof collapsed, instantly killing her and two others. If she had been delayed by even a few seconds, she would have lived.

This was difficult for me to get my twelve-year-old head around. I had grown up being told that all things happened for a reason, but what higher purpose could there be in the senselessly brutal death of a middle-aged woman on a Friday morning in Houston? Had Sharon died so that we could enjoy a few days in Florida? The thought was too horribly self-centered to contemplate.

Melville wanted desperately to believe that some part of him would survive death, but increasingly feared that he would cease to exist in his final moments. As he shut his eyes for the last time, his loves, hates, memories, gifts and aspirations would be extinguished. You can see him working out the implications in Ahab’s speech to the whale’s head. In a world where the murderer and the murdered both go to the same place, where the virtuous die senselessly, how can there be ultimate justice? Nathaniel Hawthorne, a close friend of Melville’s during the years in which Moby-Dick was being written, said of him in his journal, “He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other.”[19] Melville himself complained that to have wrestled forthrightly on the page with his questions about life, God and immortality would have been the end of his career as an author. “What I feel most moved to write, that is banned—it will not pay.”[20]

So it is even now. I’m a religious person, but that hasn’t stopped me from asking questions about our place in the world, questions that have led fellow believers to brand me a heretic, a blasphemer, preacher of a false gospel, possessed by a demon of intellectualism, a “son of the devil,” destined for hell and whatnot. Søren Kierkegaard, in his book Fear and Trembling, made the bold assertion that the one who doubts is the truest example of his or her faith, because only that person has confronted the mystery of faith in its fullness. Kierkegaard dubbed such a person a “knight of faith.” I would argue that Melville was one. So was C. S. Lewis, in his darker moments. “My hosanna,” said Dostoevsky, “is born of a furnace of doubt.”

Weirdly enough, however, the most iconic example of heroic skepticism in literature is found in the pages of the Hebrew Bible.

* * *

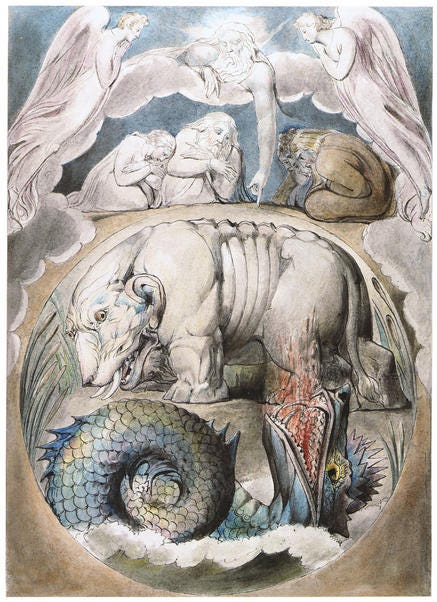

In its anger, in its poetic language, in its imagery (the leviathan), in its cry of protest against a world of manifold beauties and terrors, Moby-Dick is modeled on a much older story. The Book of Job tells of a man living in the land of Uz (somewhere in the Middle East) who is enormously wealthy—he owns “three thousand camels, and five hundred yoke of oxen”—but blameless in all his ways. Whenever his ten children gather to feast and drink, Job offers sacrifices on their behalf lest their carousing become an occasion for sin. A good man, by all accounts.

On one such feasting day, a messenger comes to Job and says, “The oxen were plowing, and the asses feeding beside them: and the Sabeans fell upon them, and took them away; yea, they have slain the servants with the edge of the sword; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee.”

“While he was yet speaking,” the story tells us, there comes another messenger who says, “The fire of God is fallen from heaven, and hath burnt up the sheep, and the servants, and consumed them; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” A third soon follows, who informs him, “The Chaldeans made out three bands, and fell upon the camels, and have carried them away, yea, and slain the servants with the edge of the sword; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” Finally there comes a fourth messenger, who delivers the crowning blow: “Thy sons and thy daughters were eating and drinking wine in their eldest brother’s house: and behold, there came a great wind from the wilderness, and smote the four corners of the house, and it fell upon the young men, and they are dead; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee.”[21]

But Job’s troubles are only beginning. Unbeknownst to him, God had laid a wager with a mysterious being known as “the Satan” (meaning adversary or obstacle). This is not the Satan of later Jewish and Christian tradition who is the author of all evil, a rebel angel, but a sort of spy or emissary who roams the earth observing its people and brings back report of his observations to the celestial court. During a recent council of the angelic host, God had pointed out the righteousness of Job, and Satan had pointed out (rather nastily, it must be said), “Hast not thou made an hedge about him, and about his house, and about all that he hath on every side? Thou hast blessed the work of his hands, and his substance is increased in the land.” Satan then exhorted the Lord, “But put forth thine hand now, and touch all that he hath, and he will curse thee to thy face.”[22]

Would he, though? There was only one way to know. God placed Job into Satan’s hand, granting him permission to inflict all manner of travails. Like the murderers descending on Macduff’s castle, Job’s livestock, servants, sons and daughters were dispatched “in one fell swoop.”[23] But Satan’s wager is frustrated. Despite losing all his riches and most of his family, Job refuses to curse God. So it’s back to the heavenly council, where Satan argues that Job’s resolve will crumble into dust once he’s afflicted with physical suffering. God gives the nod, and soon Job’s body is covered in nasty, smelly boils.

This is the point, surely, where most people would have given up and acknowledged that God, or a vindictive universe, harbored some personal vendetta against them. Even Job’s wife thinks a bit of blasphemy warranted, given the circumstances. “Dost thou still retain thine integrity? Curse God, and die.”[24] But Job remains adamant: “Shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil?”

And that’s where the earliest version of Job, the so-called Fable of Job, breaks off: with poor Job seated in the dust, scraping his boils with a potsherd, while his friends gather around him in mourning.

And that’s where the Poem of Job begins.

See, there’s now general agreement among scholars that the Book of Job consists of two distinct sections written by separate authors. One clue comes to us from the New Testament Epistle of James, which says, “You have heard of the patience of Job…”[25] But the Job of the poetic dialogue that runs from chapters 03 to 38 isn’t known for his patience. He curses the day of his birth; he laments that he didn’t die in his mother’s womb; he demands an explanation for his sufferings. He rails against providence with a venom that would seem blasphemous if it weren’t uttered by one of the heroes of scripture. Even Job’s friends, initially sympathetic, soon beseech him to chill the heck out.

Here’s what seems to have happened. Hundreds of years before the birth of Jesus, there was a story circulating in the Middle East about a man named Job who stoically suffered unthinkable hardships. God tested him, and he passed the test by refusing to complain. For this God rewarded him with lands, riches, cattle and children, far beyond what he had lost. The story was told again and again, and Job became an icon of unflinching faith.

Then—maybe around the time of the exile in Babylon in 539 BC, or shortly thereafter—an anonymous author got hold of the story. And into it they inserted a dialogue of their own between Job and his companions (and ultimately God), a long conversation in verse form about all manner of things: the fate of the dead, the problem of suffering, the pangs of being mortal. The miseries of living in a world where sometimes the only escape from oppression is death. And so much else: the futility of seeking for wisdom, the glories of the whale, the pride of the ostrich, the vexation of false friends.

And what this did—whether the original author intended it or not—was to turn the original meaning of the story inside-out. Now Job was no longer the silent, suffering hero of the opening chapters. The Job of the poem questions, accuses and demands answers. He says things that would get him shown to the door in many churches. Job’s friends, now the story’s antagonists, mouth the conventional platitudes and false consolations that the pious have spoken in all ages. But Job is having none of it.

“I was heir to futile moons,” he laments,

and wretched nights were allotted to me.

Lying down, I thought, When shall I rise?—

Each evening, I was sated with tossing till dawn…

My days are swifter than the weaver’s shuttle.

They snap off without any hope.[26]

What is my offense that I have done to You,

O Watcher of man?

Why did You make me Your target,

and I became a burden to you?

And why do You not pardon my crime

and let my sin pass away?

For soon I shall lie in the dust.

You will seek me, and I shall be gone.[27]

My whole being loathes my life.

Let me give vent to my lament.

Let me speak when my being is bitter.

I shall say to God: Do not convict me.

Inform me why You accuse me.

Is it good for You to oppress?[28]

Look, He slays me, I have no hope.

Yet my ways I’ll dispute to His face.[29]

There are echoes of Job’s complaint in a book C. S. Lewis wrote late in life. Lewis, who had never married, struck up a long-distance correspondence in the early 1950s with a singularly gifted American woman, Joy Davidman, a poet, screenwriter and erstwhile child prodigy (she acquired her Master’s degree in English literature at the age of twenty). In the wake of a failed marriage Joy moved with her two sons to England at the age of thirty-eight, where she fell increasingly under the sway of Lewis, whose books had been instrumental in her conversion. Moved by her friendship and formidable intellect, Lewis soon found himself, much to his own surprise, falling in love. “By 1955,” Lewis’s brother Warnie would later recall, they were on “close terms”: “Joy was the only woman he had met … who had a brain which matched his own in suppleness, in width of interest, in analytical grasp, and above all in humour and sense of fun.”[30] “They seemed,” said Douglas Gresham, her son, “to walk together in a glow of their own making.”[31]

They married in March 1957, but already Joy was dying of cancer. The ceremony took place at her hospital bedside; at the time her prospects seemed grim, but shortly after the wedding she made a surprise recovery. Joy and Lewis moved in together and spent the following three years in companionable bliss. She was now in her forties; he was pushing sixty. To have found each other so late, knowing that their time together would be measured in years rather than decades, charged the relationship with a keen sense of its own loss. One senses that they clung to each other the more tightly for knowing how little time they had. “I never expected to have, in my sixties,” Lewis told a friend in a tone of quiet awe, “the happiness that passed me by in my twenties.”[32]

Joy died on July 13, 1960, at the age of forty-five. In the pages of A Grief Observed, first published under a pseudonym, Lewis rages against the heavens with a vehemence that can be shocking to those who have only encountered the gentle Anglican don of his previous books. Like Job, he’s profoundly annoyed with the many friends who tried to assure him that Joy is at peace now, in heaven. “It is hard to have patience,” he writes, “with people who say, ‘There is no death’ or ‘Death doesn’t matter.’ There is death. And whatever is matters. And whatever happens has consequences, and it and they are irrevocable and irreversible.” Later in the book he laments that “all that stuff about ‘family reunions on the further shore’” in heaven is sentimental rubbish peddled by people who can’t understand metaphors: “There’s not a word of it in the Bible. And it rings false. We know it couldn’t be like that.”

As he continues to process the implications of Joy’s loss—can she still be said to exist in any real sense? Will he ever speak to her again?—Lewis adopts a view of the world and its miseries that approaches despair. A Grief Observed is not a long book, but it’s hard reading because one can hardly stand to see the brisk, beaming author of the Narnia books bereft of all hope. “Reality, looked at steadily,” he says, “is unbearable.” And later: “I am more afraid that we are really rats in a trap. Or, worse still, rats in a laboratory.”

* * *

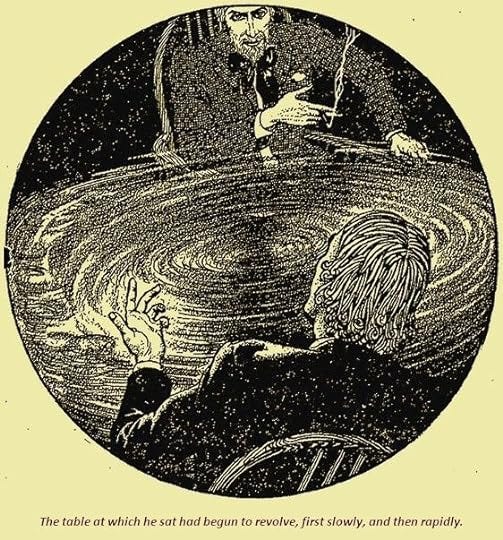

“The book of Job is chiefly remarkable,” wrote G. K. Chesterton in a 1907 essay, “… for the fact that it does not end in a way that is conventionally satisfactory. Job is not told that his misfortunes were due to his sins or a part of any plan for his improvement.”[33] The mystery of senseless tortures is one that Chesterton would take up again in the following year in his masterpiece, The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare. If you’ve not read it, set down this essay and read it at once, for I’m going to discuss the ending. It’s not long, but be warned: it’s one of the four or five strangest books ever written, and there’s no other book to which one could compare it. It’s a poem, a mystery, a spy thriller, a riddle, a fairy-tale, a rather dark comedy, and a work of existential terror. And it’s completely dazzling. Kafka, Orwell and Borges were fond of it. Susanna Clarke has called it the one book she wishes she had written.[34]

The book centers on a man named Gabriel Syme who’s recruited by a mysterious man in a dark room, whose face he never sees, into joining the London police force. The man wants Gabriel to infiltrate a gang of anarchists, all of whom are named after days of the week and who are led by the enormous, enigmatic Sunday, a man both hilarious and frightening. Replacing the previous Thursday on the council, Gabriel becomes obsessed with the mystery of the gang’s leader, who, it soon becomes clear, is more than just a man. There are hints scattered throughout the book that Sunday embodies, if not God, then certainly nature in her darker aspects. And he is toying with Gabriel, who, it turns out, is not the only secret policeman to have infiltrated the council. Every single member of the Council of Anarchists is a detective, for Sunday was the man in the dark room and recruited them all. And as they chase him through the streets of London, via elephant and hot-air balloon (I warned you that this book is insane), their sufferings in pursuit of the truth about him begin to take on the quality of a nightmare.

Why all these needless games? Why these tricks and deceptions? In the final chapter, in a scene which unfailingly moves me to tears, the six policemen corner Sunday and demand answers. As each of them recounts the agonies he’s suffered, the book expands in scope. It’s no longer merely the story of six Edwardian gentlemen having a jolly ramble, but the story of everyone whose heart has ever bled to no purpose. The book’s final and greatest surprise is that all along Chesterton has been retelling the story of Job—the story of us.

One by one, the men give voice to their complaint. “I am not happy,” says one, “because I do not understand. You let me stray a little too near to hell.”

And another adds, “If you were from the first our father and our friend, why were you also our greatest enemy? We wept, we fled in terror, the iron entered into our souls.”

And a third says only, “I wish I knew why I was hurt so much.”

Sunday receives their complaints in silence; then after a long pause, says:

“Let us remain together a little, we who have loved each other so sadly, and have fought so long. I seem to remember only centuries of heroic war, in which you were always heroes—epic on epic, iliad on iliad, and you always brothers in arms. Whether it was but recently (for time is nothing), or at the beginning of the world, I sent you out to war. I sat in the darkness, where there is not any created thing, and to you I was only a voice commanding valor and an unnatural virtue. You heard the voice in the dark, and you never heard it again … But you were men. You did not forget your secret honor, though the whole cosmos turned an engine of torture to tear it out of you.”[35]

Isn’t there something valiant, he suggests, in braving life’s terrors? In navigating the perils of this world, though we seem to be wandering alone in the dark, and with no one to guide us? Suffering bestows on each of us the potential for quiet heroism. Every life, no matter how mundane, has the quality of an epic.

It’s not really an answer, but maybe an answer isn’t what we’re looking for. Near the end of the Book of Job, a voice speaks to Job out of the tempest. Over the course of three sublime and unsettling chapters, the voice delivers everything except an explanation for Job’s travails. “Hath the rain a father? Or who hath begotten the drops of dew? Out of whose womb came the ice? And the hoary frost of heaven, who hath gendered it? … Canst thou bind the sweet influence of Pleiades, or loose the bands of Orion?”[36] It’s a remarkable passage, one that skeptics often cite as their favorite passage in the Bible. Partly that’s because the author resists the temptation to provide a conventional moral for the story. None is given because none is possible. Terrible things happen in this world and there’s no reason for it. But also, I suspect, because the voice draws Job out of himself, calling him out of self-pity and into an awareness of the grandeur of the cosmos, into that sense of wonder which Rabbi Abraham Heschel called the origin of all science and faith.

In 1930 Albert Einstein, famously an agnostic, was interviewed by American journalist George Sylvester Viereck. In the course of the interview, which ranged widely and was published in the book Glimpses of the Great, Viereck asked Einstein his views on faith. Was he an atheist, or a pantheist in the vein of Spinoza? Declaring the question “difficult,” Einstein replied with a parable:

“The human mind, no matter how highly trained, cannot grasp the universe. We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects … We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly. Our limited minds cannot grasp the mysterious force that sways the constellations.”

Given his immense learning, Einstein’s response betrays an astonishing humility. We are born into a world beset by terrors and wonders on every side. Like the sparrow in the feasting hall, we don’t know how we came to be here or where we’re going. If we weren’t so accustomed to the world through long familiarity, we would be living in perpetual amazement. Einstein—like Lewis, like Melville, like the great fairy-tale writers—sought to pull back the veil of habit so that we could see with fresh eyes, and be startled.

My favorite passage in Moby-Dick comes towards the book’s end. It involves “the most insignificant of the Pequod’s crew,” a Black cabin-boy named Pip who wins the love of Ahab and the other men with his bright spirit and merry tambourine-playing. When one of the after-oarsmen sprains his hand, Pip is enlisted to replace him. This proves to be a bad idea, as Pip is terrified of water and doesn’t react well to being placed on the open sea in a whaleboat.

An unhappy set of circumstances results in Pip being abandoned in the water, “a whole mile of shoreless ocean” between him and the nearest crewman. Stranded alone “in the middle of such a heartless immensity,” he loses his mind; and when the ship at last rescues him, he can no longer speak except in repeated, incoherent phrases. Ishmael doesn’t think him mad, however. Pip can’t explain what he saw on the water, but Ishmael imagines it, in a sequence that for sheer grandeur and hair-curling sublimity is unrivaled in any book before or since:

“The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic.”[37]

Perhaps it’s true, as the ultimate fate of Pip and the rest of the crew attests, that life in this mortal world is miserable and senseless and bleak. But every once in a great while, a man or woman gifted with extraordinary vision will shock us awake for a moment, as Melville does here, and show us the hidden glory at the back of things.

[1] Jones, Dan. The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England. Viking, 2012.

[2] Castor, Helen. She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England before Elizabeth. HarperCollins, 2011.

[3] Spencer, Charles. The White Ship: Conquest, Anarchy and the Wrecking of Henry I’s Dream. William Collins, 2020.

[4] When Christ and His Saints Slept is also the title of a novel by Sharon Kay Penman that depicts the sinking of the White Ship in an early chapter. Although a work of fiction, Penman’s account is remarkably faithful to the historical record.

[5] Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, epilogue.

[6] Kinzer, Steve. “Call Me Bush.” The Guardian. December 8, 2008. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2008/dec/08/moby-dick-national-book

[7] Edinger, Edward. Melville’s Moby-Dick: An American Nekyia. Inner City Books, 1995.

[8] Philbrick, Nathaniel. Why Read Moby-Dick? Penguin, 2011.

[9] Though the book was published eight years before Origin of the Species, Melville uncannily anticipates some of Darwin’s discoveries.

[10] Melville, Moby-Dick, chapter 10. Arguably one of the reasons this novel flopped when first published is because it was so far ahead of its own era.

[11] Herbert, Walter T. Moby-Dick and Calvinism: A World Dismantled. Rutgers, 1977. Dr. Herbert was my Melville professor at Southwestern.

[12] Melville, Moby-Dick, chapter 132.

[13] ibid, chapter 42.

[14] Heller, Joseph. Catch-22. Modern Library, 1961, chapter 17.

[15] Lewis, C. S. Mere Christianity. HarperCollins, 2009.

[16] Philbrick, Why Read Moby-Dick?

[17] ibid, chapter 70.

[18] Name changed for privacy reasons.

[19] quoted in Philbrick, chapter 28.

[20] ibid, chapter 12.

[21] Job 1:14-19, KJV.

[22] Job 1:10-11.

[23] Shakespeare, William. Macbeth, IV.iii.258.

[24] Job 2:9.

[25] James 5:11, NKJV.

[26] Alter, Robert. The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary. Job 7:3-6.

[27] ibid, vv. 20-21.

[28] ibid, 10:1-3a.

[29] ibid, 13:16.

[30] Lewis. C. S. Letters of C. S. Lewis. HarperCollins, 2017.

[31] Lewis, C. S. A Grief Observed. Preface by Douglas Gresham. HarperCollins, 2009.

[32] ibid.

[33] Chesterton, G. K. “Introduction to the Book of Job.” https://www.chesterton.org/introduction-to-job/

[34] Susanna Clarke. “Susanna Clarke: ‘Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman Taught Me to Be Courageous in Writing.’ The Guardian. September 3, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/sep/03/susanna-clarke-neil-gaimans-the-sandman-taught-me-to-be-courageous-in-writing

[35] Chesterton, G. K. The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare. Penguin Classics, 2011.

[36] Job 38:28-31, KJV

[37] Melville, Moby-Dick, chapter 93.

I'm also reminded of one of my favorite lines in popular song, from Lightfoot' s THE WRECK OF THE RFMUND FITZGERALD: ""Does anyone know where the love of God goes when the waves turn the minutes to hours...?"

Boze, this is a tour de force on the immense impenetrability of mystery. Like a great cubist artist, you look at this reality from many angles--penetrating insights from Melville, Job, C.S. Lewis, Chesterton . . .

Indeed, as you quote Einstein, “Our limited minds cannot grasp the mysterious force that sways the constellations."

The rest methinks is silence.

Thanks for this very erudite, deep, wide reflection on the limits of our knowing and understanding.