The Shadow Canon 02: Inanna's Journey to Hell

Infernal Visions in Ancient & Medieval Literature

On the night when Howard Storm first died, he saw visions of hell.

It was June 1985. Howard, a thirty-eight-year-old visual artist and professor at Northern Kentucky University, had accompanied a group of students on a trip to Paris. Joining him was his wife Beverly.

On the final Saturday of their visit, Howard seemed to be in good health. That morning, a bright, clear morning in Paris, they visited Eugene Delacroix’s studio, preserved to look as it had done during the painter’s life. “We arrived at the Delacroix Museum at nine,” he writes in his memoir, My Descent into Death. “And just before eleven o’clock we returned to our hotel room to get our little group ready to go to the Georges Pompidou Center of Modern Art. This was to be one of the high points of the tour of Europe.” It was then that his troubles started.

Back in his room, Howard was overcome with a feeling of nausea. The antacid tablets he had been taking for recurring indigestion proved ineffective. While chatting with a student he felt a “searing pain” in his abdomen. At first he thought a bullet had struck him. “One minute I was talking with Monica about our upcoming museum visit,” he would later write, “and the next I was writhing on the floor, consumed with pain. I had collapsed at the foot of the bed … Constricted between the bed and the wall, I struggled to control my rising panic.”

Howard summoned Beverly, urging her to get a doctor. Paralyzed with concern, she hesitated. Howard let out a string of curses. Beverly reached for the phone and rang the hotel desk. A doctor arrived within ten minutes. After examining Howard’s stomach, the doctor informed him that his small intestine had been punctured. He needed surgery immediately, or he would be dead within a matter of hours. When Howard asked if the operation could be postponed until their return to America on Monday, he was informed that he wouldn’t survive the trip.

Within moments, two young men arrived from the local hospital and assisted Howard into an elevator. The elevator stopped one floor above the street. He was lifted down a long, winding staircase and into a waiting ambulance.

Howard was taken to a hospital where the staff spoke only French. French hospitals, as he soon learned, are typically understaffed on the weekends. Only one surgeon was available that day, and as Howard waited for their arrival the hours passed. “They didn’t give me any medication whatsoever, no treatment whatsoever,” he recalled in a 1997 episode of Unsolved Mysteries. “After six or seven hours I had a very strong feeling that I wasn’t going to make it. And after ten hours, I knew I wasn’t.”

Tearfully, Howard said goodbye to his wife. A long-time atheist, he shut his eyes, resigned to the nothingness of oblivion. “I knew that what would happen next would be the end of any kind of consciousness or existence,” he writes. “… I knew for certain that there was no such thing as life after death. Only simple-minded people believed in that sort of thing.”

When Howard next opened his eyes, he found that he was standing upright. Beverly sat in a chair beside the bed. He spoke but she didn’t answer. The pain in his stomach had begun to subside, but he was aware now of other feelings—the contracting of his muscles, the veins in his ears, the bones in his hands. His senses were acutely attuned to the room around him. “This is no dream,” he soon realized. “I am more alive than I have ever been.”

Glancing down at the bed, Howard was amazed to see his own body. “I was horrified to see the resemblance that it had to my own face,” he would later say. “It looked so meaningless, like a husk, empty and lifeless.” He was beginning to wonder if maybe he had gone mad when he heard voices in the corridor—men’s voices, women’s voices, young and old. They were calling his name. Confused by the fact that the voices seemed to be speaking in English, Howard left the room.

There he found a number of rather ordinary-looking people. At first he thought they were nurses. “Come out here,” they said. “We’ve been waiting for you for a long time.” When Howard protested that he needed surgery, they replied, “We can get you fixed up. Don’t you want to get better?”

Thinking they intended to lead him to the OR, Howard followed them down the hallway. As he approached, they seemed to get more distant. “It was like being in a plane passing through thick clouds,” he writes. “The people were off in the distance and I couldn’t see them very clearly … Their clothes were gray and they were pale. As I tried to get close to them to identify them, they quickly withdrew deeper into the fog. So I had to follow farther and farther into the thick atmosphere. I could never get closer to them than ten feet.” Howard had about a million questions. Who were they? Where was Beverly? They wouldn’t answer.

The corridor seemed to lengthen indefinitely. Howard had been walking for miles, yet when he turned round he could still see the door of his room faintly in the distance. “There were no walls of any kind. The floor … had no features; there was no incline or decline.” It was unclear to him how much time had passed. And the people around him were whispering to one another with increasing aggression. He knew they were making fun of him. They began to yell, then to push him, in an effort to speed him along. Sensing their bad intentions, Howard decided to fight back.

“A wild frenzy of taunting, screaming, and hitting ensued,” Howard writes. “I fought like a wild man. As I swung and kicked at them, they bit and tore back at me. All the while it was obvious that they were having great fun. Even though I couldn’t see anything in the darkness, I was aware that there were dozens or hundreds of them all around and over me. My attempts to fight back only provoked greater merriment. As I continued to defend myself, I was aware that they weren’t in any hurry to annihilate me. They were playing with me just as a cat plays with a mouse. Every new assault brought howls of cacophonous laughter. They began to tear off pieces of my flesh. I realized that I was being taken apart and eaten alive, methodically, slowly, so that their entertainment would last as long as possible.”

* * *

Though Howard didn’t know it at the time, he had just embarked on one of literature’s oldest journeys. The narrative motif of the descent into the underworld takes us back 4,000 years to the very roots of myth. “Inanna’s Journey to Hell” (translated by N. K. Sandars in the book Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia for Penguin Classics) establishes a number of conventions for such stories that will recur in subsequent myths—the infernal journeys of Odysseus, Aeneas and Dante, the parables of Bede and Gregory the Great—and in supposed near-death visions up to the present day.

One might object that by bundling Howard’s journey (told, whatever its validity, with utmost sincerity) and the quests of Heracles, Persephone and others under the same umbrella, I risk conflating a real human experience with stories that were always known to be fiction. But the boundaries between NDEs and fictional excursions into the beyond are porous. It’s been suggested that portrayals of heaven and hell in ancient literature preserve memories of real near-death encounters, which explains why certain elements—the tunnel of light, river crossings, meetings with mysterious beings—remain permanent fixtures of the journey. Howard doesn’t seem to have been acquainted with ancient near eastern poetry, but his story contains striking parallels with Inanna’s underworld journey, and with other, lesser-known visions of the beyond that only a specialist in afterlife literature would know about. His story has the power to move us because he experienced firsthand a living myth.

“Inanna’s Journey to Hell” belongs to a cycle of poems depicting the coming to maturity of the goddess Inanna, queen of heaven and earth, whose sister Ereshkigal governs the land of the dead. In a previous poem Inanna had courted and won the love of Dumuzi, an agricultural and fertility deity; the two declare their love in a series of lyric verses that recall the Song of Songs and comprise what has been called “one of the most beautiful love poems in world literature.” As the story of her underworld journey begins, Inanna is approaching middle age. She’s found domestic happiness and stolen the “holy laws of heaven and earth” from her grandfather Enki during a drinking binge, thereby acquiring “all the basic arts, rites, judicial skills, powers of speech, lovemaking techniques, musical talents, and crafts of civilization.”[1] Inanna has become as successful in her own way as Gilgamesh, a fellow Sumerian monarch whose story intersects with hers at odd moments.

There’s much debate over the question of why Inanna feels compelled to visit the realm of the dead. The poem itself leaves her motivations opaque: it begins in medias res, telling us only, “This lady left earth and heaven and went down into the pit.”[2] Later, standing at the gates of hell, she claims to have come “for my elder sister, for Ereshkigal, because of her lord, Gugalanna, who was killed.” Gugalanna, of course, was the Bull of Heaven slain by Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and the husband of Ereshkigal. Having learned of his death, Inanna says, she’s come to grieve with her sister. But the text calls this a lie, and it’s been suggested that she has some hidden agenda, perhaps hoping to seize possession of the underworld from Ereshkigal and be the ruler of several domains at once.

Whatever her ostensible reasons, it’s surely not without meaning that Inanna makes the journey at midlife—the age at which Howard Storm saw hell, the age at which Carl Jung had a troubling near-death vision of restless souls trapped in a miserable postmortem existence, the age, most famously, of Dante, who at the age of thirty-five, “midway in the journey of our life … came to myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost”[3] (lines that echo the lament of the biblical king Hezekiah: “In the midst of my days I shall go to the gates of the nether region”). Jung saw midlife as the point at which the soul begins to cast off the status quo that has bound us, the unexamined impulses and habits developed over a lifetime. The shedding of long-cherished personas can leave us feeling naked and helpless. It’s also at this age that we begin to lose our parents and elders. As the generations before us die off, we’re confronted with a renewed sense of responsibility and the inescapable certainty of mortality, our own and that of others. (“As we grow older,” wrote T. S. Eliot, “The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated / Of dead and living.”) But this journey through the “Middle Passage,” as James Hollis calls it, is necessary “to earn the vitality and wisdom of mature aging”; it “represents a summons from within to move from the provisional life to true adulthood, from the false self to authenticity.”[4] Hercule Poirot, that master psychologist of the female psyche, tells Hastings, “In the autumn of a woman’s life, there comes always one mad moment when she longs for romance, for adventure—before it is too late.”[5] Swiss Jungian scholar Marie-Louise von Franz says this moment may manifest in a sudden flowering of youthful spontaneity which a woman had endeavored to suppress in the first half of her life.[6]

And for Inanna at midlife, this sudden spontaneity leads her to the realm of the dead.

“In the long poem of Inanna’s Journey,” Sandars writes, “many of the great archetypal themes are joined: the descent to hell, the sevenfold approach, death and rebirth, the pursuit, the mourning women.” Prior to setting out on her journey, she clothes herself in sandals, a crown, a golden ring, a gem of lapis lazuli and a “robe of sovereignty,” a scene that has been recycled endlessly in literature and popular culture whenever the hero is given weapons, and exchanges his or her old clothes for new (Harry Potter acquiring robes and wand, Robert Oppenheimer taking up fedora and pipe).

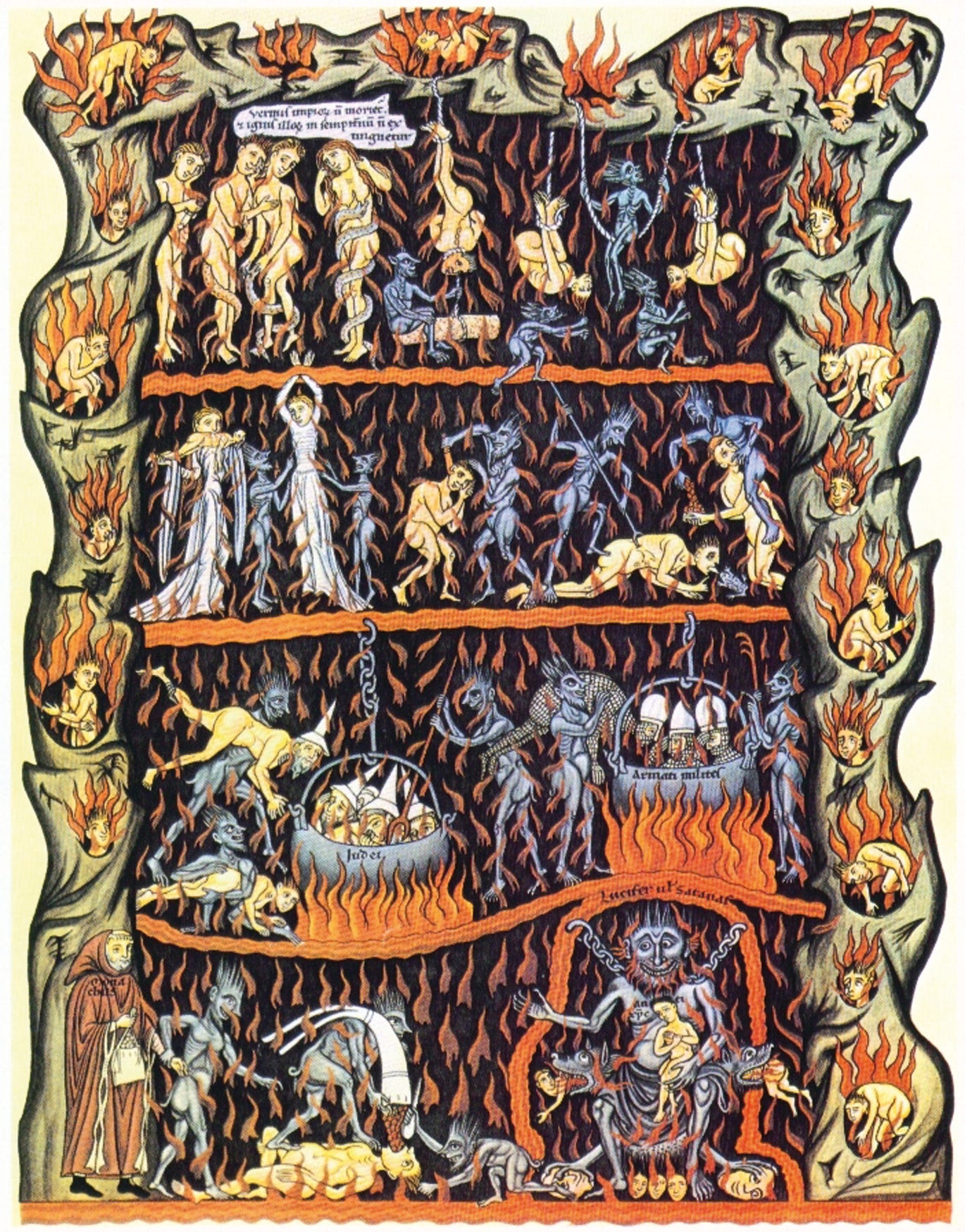

As with Gilgamesh, we’re not told much about the journey, only that she “walked” until she reached “the lapis lazuli halls of hell.” The landscape is further developed in a short poem, “The Sumerian Underworld,” and it’s worth noting that while this is the first extant description of the underworld in literature, it’s already assumed the basic contours it will possess for the next two thousand years: the slippery river bank, the gates guarded by a beast (in this case a lion with birds’ feet and human hands), the meadows for the souls of the virtuous, the gradations of reward and punishment. In ancient and classical myth it was generally assumed that all the dead resided in one place; not until the New Testament era do we begin to see the saved and the damned living in separate locations.

On arrival, Inanna must pass through seven walls with seven gates. Here she’s stripped of her garments one by one, in a sobering portrait of the dissolution of the ego as the soul journeys through the later stages of life. “The imagery of being stripped down,” writes Lansing Smith, “of having all that one had struggled to achieve brutally taken away, leaving one naked in the presence of death, is absolutely basic to the threshold crossing of the hero’s journey.” In a similar vein, Howard Storm says the “mob” of the damned who attacked him, ripping off his clothes and tearing at his flesh, sought to destroy him “not only physically but psychologically, emotionally.” “What was the point of living,” he wondered, “to end up like this? I never really accomplished anything very significant; now I end up in this place of torment.” Middle age has a way of stripping our achievements from us. We begin to assess our lives and realize, often to our dismay, that the things we believed mattered in our youth no longer matter. We’ve built an “empire of dirt.” We’ve “labored in vain,” and “spent our strength for nothing.”[7]

“For about a quarter of a century,” writes Thomas Moore in his book Ageless Soul, “you don’t think much about age and don’t imagine the end. The first taste is something of a shock, as literal youth is left behind. The next phase is a gradual process that takes years, as you create structures for your life and become somebody else. Fourth, you slowly realize how many ways you are no longer young.”[8] Having recently turned thirty-eight, I’m reminded daily of how old I’m getting. In the space of a few years I went from being attuned to youth culture and hopeful about the future to fretting about the effect of screens on literacy and worried the next generation is going to doom us all. (Someone on Twitter said I have the vibe of a “cantankerous ninety-year-old man yelling at clouds,” which is not something anyone would have said about me even two years ago.) It hasn’t escaped my attention that I’m nearly forty and still haven’t published a book. I lie awake at night in a cold sweat fearing that my best years have been wasted, and that by the time my first book is finished there will be no one left who still wants to read books. And despite all the positive developments of the past couple years—being happily married, having an audience—there’s a fist of anxiety in my belly that never unclenches. What if I spent three decades preparing for a career that’s now becoming obsolete? What if I never accomplish the things I wanted to accomplish? What was all this for?

* * *

If I find it hard to believe Howard literally walked down a hospital corridor into another realm, it’s because, well, I’ve studied the long history of hell visions in literature. And it’s inescapably true that they are, to some degree, culturally conditioned. Certainly there are continuities through the ages, but Howard’s is very much the vision of a man living in twentieth-century America. A man living in sixth-century Europe would have had an altogether different encounter, and returned to the land of the living with a radically different message.

We know this because there are records of supposed hellish journeys in the literature of sixth-century Europe (and journeys to purgatory, though such journeys are intriguingly less common now than they were during the Middle Ages). Pope Gregory spoke of a story he had heard “from reliable witnesses”[9] about a man named Stephen who was sent to hell by mistake. When Stephen was brought before the judge of hell, the judge informed him that another Stephen, a blacksmith who lived in the same town, was supposed to have died but somehow the two Stephens had gotten mixed up, presumably owing to some whacky clerical error in the infernal bureaucracy. (Fans of The Good Place will recognize this as the premise of the first season.) But during his brief stay in hell, the good Stephen, like Howard, “saw many things that he did not believe in when he had heard about them while he was alive.” He claimed to have seen a bridge spanning a black river “veiled in mist.” When the wicked attempted to cross, they slipped and tumbled into the dark waters, but the souls of the virtuous glided easily across into pleasant meadows.

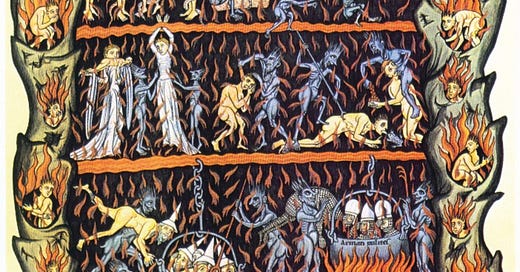

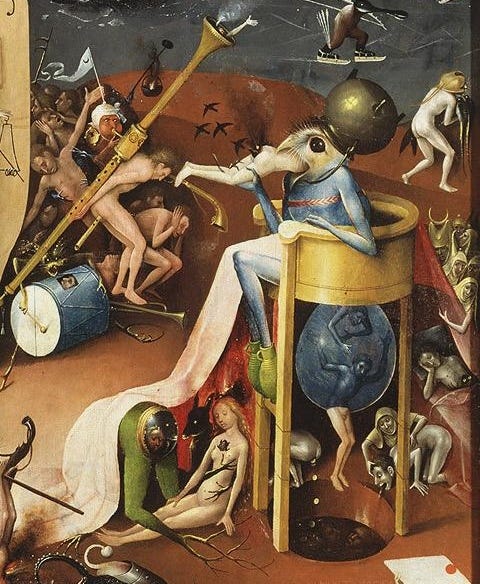

The human mind has never lacked for creativity in imagining hells of various kinds. For whatever reason, heaven is beyond our capacities to envision, which is why the same imagery (of clouds, music, meadows) recurs monotonously, leading to grumblings down through the years that heaven must be a very dull place indeed. (“When you live in the desert,” says Johann Hari, invoking Gilgamesh, “a spring seems like paradise. But when you have had the spring for a thousand years, won’t you be sick of it?” To which Peter Kreeft responds, “Even on earth, the only people who are never bored are lovers.”) Hell, however, has been tricked out with every color in the artist’s toolbox. The late medieval Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, in the right panel of his terrifying triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, displays a surreal hellscape in which giant ears carry knives, a rabbit spirits away the body of a man naked and bleeding, a bird-like monster eats a person with one orifice while excreting a second person with another. (Bosch rivals Lewis Carroll in the weirdness of his imaginative vision.) Hinduism speaks of a temporary state known as Naraka where souls are cleansed of their sins before being reborn. This underworld is governed by Lord Yama, who sits on a buffalo and metes out creative punishments for offenses both serious and petty: those who cut down the canopies of trees suffer barrages of thunder and lightning; “men who hit on their daughters-in-law” are burned with coals; milk-sellers (yes, milk-sellers!) are beaten with chains.[10]

What might be my favorite portrayal of the afterlife in myth is the Chinese Diyu, a massive realm of scholars, clerks and courtiers running a celestial bureaucracy not unlike the one depicted in the Pixar film Coco. There’s a real earthly city, Fengdu Ghost City, featuring a “Terrace for Viewing One’s Own Village.” It’s said that the souls of the dead pause here in the midst of their journey to ascend the terrace and get a final look at their loved ones before moving on. Ken Jennings calls this a “diabolical torture” designed to show the damned that their families and friends are no longer thinking about them. As someone who has long dreaded being ignored and forgotten, I suspect this would be the ultimate hell for me: seeing the books I wrote gathering dust, my name and memory gradually erased from the earth. And yet being forgotten has been the fate of most people in most eras. “There is no remembrance of former things,” says the author of one of the few ancient books we still read.[11]

* * *

I don’t know whether or not Howard Storm saw glimpses of hell in a Paris hospital. I don’t want to discount the possibility (“more things in heaven and earth” and so forth), but I think “did he really die?” is asking the wrong question. I’m more interested in what his journey, and the many similar journeys reported throughout history, have to say about us as people living in this world.

Howard has made his own views of his experience known. Prior to his death, he was not a kind man. He claims to have treated his loved ones with cruelty and aggression; his anger was a terrible thing to witness. Shortly after escaping the crazed mob, he met several benevolent beings (he thinks they were angels) who showed him scenes from his life. (The life review, it should be noted, is another standard motif of the underworld descent: when Inanna crosses the seventh threshold, Ereshkigal fixes her with the eye of death and hangs her up naked on a wall as words of “wrath and guilt” are spoken against her.) Howard witnessed the neglect of his parents as a boy and his resulting inability to show proper attention to his own children. “The most disturbing behaviors … were the times when I cared more about my career as an artist and college professor than about their need to be loved.” Their emotional abandonment, he writes, “was devastating to review.”

Towards the end of the clip reel, Howard was informed he was being sent back into the world. The experience of death left him profoundly changed. Enrolling in seminary, within a few years he became pastor of the Zion United Church of Christ in Norwood, Ohio. During his public appearances, he’s spoken passionately about the need for people to love each other. Listening to him speak, one gets the impression that what really troubled him during his alleged journey wasn’t so much hell itself but the prospect of a wasted life—the fact that he spent thirty-eight years largely living for himself, and what a lifetime of selfish living can do to a person. It’s the lesson of A Christmas Carol again: “No space of regret can make amends for one life’s opportunity missed.”

Even if you’re not convinced he literally died, that’s a lesson worth heeding.

One could choose to see the story as Howard does, but there are other ways of viewing it. Here’s one. During a summer weekend in Paris, in a moment of extreme stress and frightened by the prospect of an imminent death, a man approaching middle age looked back upon his life. Detritus of guilt and regret that had been pooling in the back of his mind for a number of years, largely ignored, could be ignored no more. As his body began the process of shutting down, his brain took him on a journey into the unconscious, a journey into his own past, where—like Inanna, like Scrooge—his soul was stripped to its essence. Shorn of all pretense, for the first time he saw himself as he truly was, and the shipwreck he had made of his life.

[1] Lansing Smith, Evans. The Hero Journey in Literature: Parables of Poesis. University Press of America, 1997.

[2] Sandars, N. K. Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia. Penguin Classics, 1971.

[3] Alighieri, Dante. The Inferno. Translated by Robert and Jean Hollander. Doubleday, 2002.

[4] Hollis, James. The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Inner City Books, 1993.

[5] Christie, Agatha. “The Cornish Mystery.” The Complete Short Stories of Hercule Poirot. William Morrow, 2013.

[6] Von Franz, Marie-Louise. The Feminine in Fairy-Tales: Revised Edition. Shambhala, 1993.

[7] Isaiah 49:4.

[8] Moore, Thomas. Ageless Soul: The Lifelong Journey Toward Meaning and Joy. St. Martin’s Press, 2024.

[9] Bruce, Scott G. The Penguin Book of Hell. Penguin Classics, 2018.

[10] Jennings, Ken. 100 Places to See after You Die: A Travel Guide to the Afterlife. Scribner, 2023.

[11] Ecclesiastes 1:11.

Wowser, Boze. A masterful examination of near-death experiences and the myriad ways that we fragile humans have considered this inevitability . . . how we deny and avoid it . . . how we could embrace the "grim" reality and live more fully and meaningfully.

Truly, this essay edifies and exhorts.

Thanks so much. May we not wait until the bitter end to live examined lives!!!

I’ve really enjoyed these shadow canon’s so far. I appreciate the time and thought you’ve put into this (even if “um, no” it’s not a poem or hell or whatever). I didn’t think I’d be adding “Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia” to my TBR list, but here we are.