Every Novel by Charles Dickens from Worst to Best

a joint ranking by Boze and Rach

You could make a case—you would be wrong, because Shakespeare exists, but you could make a case—that Dickens is the greatest writer the English language has produced. As it stands, he’s comfortably lodged in second place and it’s unlikely that he’ll ever yield the position to another. Book editor Cheryl Klein once wrote that writing talent is a combination of five traits—imagination, insight, observation, writing craft and dramatic skill—and that she had never known an author who excelled in all five. But Dickens possessed them all. He seems to have been almost genetically predisposed to write perfect books, the way Michael Phelps was built to swim or Secretariat to win races. No other novelist evinces the same combination of effortless characterization, vibrant description and perfect plotting, that mysterious ability to arrange the events of a story in such brilliant sequence that your hairs stand on end.

For some time before the Dickens Chronological Reading Club ended, we (Rach and I) had been contemplating doing a ranking of every Dickens novel. This was a project close to our hearts: for three years we ran the reading club together, and shortly before it ended, we married. During those three years we read the books aloud, listened to them on audio, unearthed obscure short stories and essays from the dusty corners of the Dickens canon and recited our favorite passages so often we nearly committed them to memory. We discussed how it might feel to live in a Victorian rookery with birds circling the windows, or sit in the Greenwich Naval Hospital on a dark, dismal day in November and observe “the eyes and throats of ancient … pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards.” We have been quite mad for all things Dickens.

Before we embark, some rules. (“Business first, pleasure arterwards, as King Richard the Third said when he stabbed the t’other king in the Tower, afore he smothered the babbies.”) We’re only ranking the fourteen canonical novels and the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood, so you won’t see A Christmas Carol (one of the most perfect things ever written, but at only 30,000 words it hardly qualifies as a novel). Nor will you see any of the other Christmas books on this list. Likewise for American Notes, Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz, The Uncommercial Traveller, &c., though we’ve read and recommend them. Indeed, some of our favorite pieces by Dickens—“Mr. Tulrumble,” “The Magic Fishbone,” “The Signal-Man,” “The Gin Palace,” that passage in his letters where he (playfully, we assume) debates throwing himself in the Thames because the young Queen Victoria doesn’t fancy him—didn’t make it onto the list. When you start really digging into Dickens, you find that his novels are a small portion of his published work. But it’s largely on this portion that his fame (deservedly) rests.

All that said… “lead on, spirit—the night is waning fast!”

14. Hard Times (1854)

I hope some of our beloved Dickensian friends will not take offense at this placement of Hard Times—for really, the “least” of Dickens’s books is, for us, better than nearly anything else. And some of our most brilliant friends love Dickens’s hammer-blow at utilitarianism, logic-over-fancy, and the divorce laws. While we love much of what Dickens is attempting to do here, we just didn’t love (as much) the way he did it. It had far more of the overtly allegorical/representative about it than is typical for the ridiculously generous and distinct Dickensian characterization. (Though Gradgrind is a brilliant figure and Gradgrindian is up there with Pecksniffery for glorious character adjectivery.) Though Sissy Jupe is lovely, I found Louisa and Gradgrind both less successful, as characters, than some earlier parallels—e.g. Floy, Edith, and Mr. Dombey. Too, we found the sentiment surrounding Stephen Blackpool’s long monologues and tragic story less effective. Still, it is our glorious Dickens. –Rach

13. Martin Chuzzlewit (1844)

Martin Chuzzlewit surely has one of the most atmospheric openings of any novel, and some really knock-out characters. Revolving around the inheritance—and disinheritance—to be left by the jaded Martin Chuzzlewit (the elder) and on his relationship with his family and ward, Dickens tackles the subjects of selfishness and greed with his usual flair. The second half, though a fantastic spoof of America—and it is fun to read this in conjunction with Dickens’s bitingly humorous and insightful American Notes—I found the English parts far more interesting. Especially in the character of Tom Pinch, who is one of Dickens’s greats. –Rach

12. Barnaby Rudge (1841)

During our Dickens Chronological Reading Club, this one became a surprise hit, and it was hard to find a place to put it here on our list, as I would tend to rank it higher. Barnaby Rudge was quite a long-term labor for Dickens, and his only historical novel besides A Tale of Two Cities. Like A Tale, Barnaby evinces Dickens’s concern for the social issues of his day and the potential for mob violence by taking his readers along on a journey with a young man with an intellectual or developmental disability (and his amazing pet raven) as he gets caught up in the Gordon Riots of the 1780s. The tale is full of Gothic atmosphere and begins on a note of murder and ghostly visitations. I hope you give it a go—I’m looking forward to doing another reread myself very soon. –Rach

11. Oliver Twist (1838)

After the comic rambles of Pickwick, his first novel, Dickens was keen to prove his skills as a serious dramatic writer. He made a hard swerve into drama (and melodrama) with his second book, the story of an orphaned boy who falls in with a gang of thieves led by the irascible Fagin. The cleverness of Dickens’s plotting in this novel isn’t fully appreciated; it’s the Victorian equivalent of something like Breaking Bad, building to a climax that is no less thrilling and emotionally gutting. What’s remarkable (and infuriating) is that he largely improvised the plot as he wrote—and that he was only twenty-six. —Boze

10. The Old Curiosity Shop (1841)

This early picaresque novel about a young woman and her grandfather wandering across a surreal English landscape of rogues, freaks and ne’er-do-wells, pursued by the malevolent dwarf Quilp, has the dreamlike quality of Pilgrim’s Progress or a romance of the Middle Ages. Thoroughly rooted in the sentimental tradition, and featuring a heroine, Little Nell, who embodies some of young Dickens’s more annoying tendencies with respect to female characters (Oscar Wilde is supposed to have said that you would need a heart of stone to read about her death without laughing), it nonetheless holds together because of its strangeness, a strangeness that occasionally assumes the quality of a nightmare. —Boze

09. Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

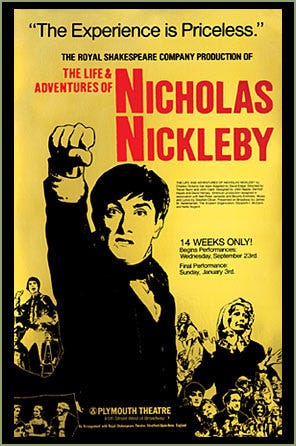

In some ways, I would put this higher—although I have no idea what it would replace—simply because it is one of the funniest and most moving stories in existence. As Boze has written during our Dickens Club period, Nickleby is, somehow, a combination of the best of sunny and picaresque Pickwick with the most sentimental and tragic of Oliver Twist, the two works that preceded it. It is as though Dickens was finding his way; it is the consummate sort of “streaky bacon” tale—a term which Dickens used to indicate the layers of humor mixed with pathos that make for effective storytelling. Nickleby also has some of Dickens’s most genius comic creations, from Mrs. Nickleby and Mr. Mantalini, to the mad gentleman in small-clothes who throws cucumbers as an eccentric wooing technique. (Boze memorized his entire, mad speech to Mrs. Nickleby as his marriage proposal to me…what could I say except, “Barkis is willin’!”?) An early gift from Boze was the Nonesuch edition of this novel, and I am forever enamored of the 1982 recorded stage production of the 8 ½ hour stage miracle with Roger Rees and Edward Petherbridge. If you love humor, theater, villains getting the most poetical justice…this is for you. –Rach

08. Dombey and Son (1848)

Dickens’s mid-career masterpiece centers on the relationship between Paul Dombey, a shipping magnate, and his daughter Florence, and has much to say about family, money, marriage, and the kind of pride that isolates and destroys. In the figure of Edith Dombey, Paul’s second wife, Dickens invents one of his best female characters, and the dissolution of the Dombey’s marriage mirrors and anticipates Dickens’s own. Unjustly neglected because of the books that immediately followed it, Dombey and Son represents Dickens’s most successful fusion to this point of realism and fairy-tale. —Boze

07. Our Mutual Friend (1865)

“The river had an awful look, the buildings on the banks were muffled in black shrouds, and the reflected lights seemed to originate deep in the water, as if the spectres of suicides were holding them to show where they went down. The wild moon and clouds were as restless as an evil conscience in a tumbled bed, and the very shadow of the immensity of London seemed to lie oppressively upon the river.”

Though this is a quote from Dickens’s essay, “Night Walks,” it might as well sum up the atmosphere of this consummately London-centered novel, with its majestic and secretive River who gives life and death equally. It’s hard to rank this any lower than the top five, as it is not only great social satire and a marvelous story, but has some of Dickens’s best characters in any novel—in other words, some of the greatest characters of all time. The book has, arguably, two of his three strongest female leads in Bella Wilfer and Lizzie Hexam, and my very favorite Dickensian character—along with Sam Weller and Sydney Carton—in Miss Jenny Wren, the quirky dolls’ dressmaker. It also has one of his greatest villains in the haunted, insecure Bradley Headstone. This really is little short of perfection, and I hope you’ll love it too. –Rach

06. Great Expectations (1861)

An early scene in which the orphaned Pip, contemplating his parents’ gravestone, is violently accosted by an escaped convict named Magwitch, sets the tone for the rest of the book, which has some claim to being the eeriest novel Dickens ever wrote. Magwitch and Miss Havisham seem to have wandered in out of some demented tale by the Grimm Brothers, and Dickens powerfully subverts the Cinderella story arcs of his previous novels to devastating effect. By the end, Pip’s “great expectations” have been utterly crushed, but it’s these youthful humiliations and the loss of his idealism that make this one of the great coming-of-age novels. —Boze

05. Little Dorrit (1857)

For me, Little Dorrit remains in my top three Dickens works—which means it is certainly in my top five books of all time—with all of its glorious strangeness. Set a couple of decades before Dickens wrote it, the story revolves around a young woman, Amy Dorrit—called “Little Dorrit”—who has the distinction of being born in the Marshalsea prison for debtors. Her father, William Dorrit, one of the great tragic characters, had been imprisoned for mysterious reasons, and has been there so long that he has come to be known as “the Father of the Marshalsea.” The Dorrits are aided by a kind stranger, Arthur Clennam. Now entering midlife after a dismal twenty years abroad working at his family merchant business, Arthur realizes that he has let much of his life slip by him and wants to make reparation for some wrong that was done by his parents years before—a wrong which haunted Arthur’s father before his death. Arthur fears it might have something to do with the misfortunes of the Dorrit family, and he is determined to find out the truth. Though the resolution is somewhat convoluted and it has a particularly moustache-twirling villain, Little Dorrit has my favorite settings and atmosphere of any Dickens, and my favorite leading romantic pair. –Rach

04. The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870)

Had Dickens lived long enough to finish the final half of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, we might now be talking about it as one of the most perfect books ever written. Here, Dickens not only out-Wilkies Wilkie Collins but does so in a delightfully Gothic and humorous fashion. He also returns to his childhood setting, Rochester, under the fictional name of Cloisterham. The story revolves around a troubled choirmaster, John Jasper—one of Dickens’s great characters, and the fulfilment of the terrifying Bradley Headstone in Our Mutual Friend—who is living a double-life in a grimy London opium den, where his strangest and most violent fantasies come to life. Typically, the violent fantasies revolve around his beloved—or is he?—nephew, Edwin Drood, the golden boy who seems to live an undeservedly blessed existence, including in the long-arranged betrothal with the young woman that John Jasper himself wants to make his own. On one stormy Christmas Eve night, Edwin Drood goes mysteriously missing, his last contact having, insofar as we know, been the hot-tempered Neville Landless, on whom Jasper is determined to throw suspicion and have revenge. Is Edwin Drood actually dead, or has he been in hiding or spirited away? If dead, who killed him? It is one of the great literary mysteries, and half the fun of this deranged and delightful half-novel is trying to figure it out. Much ink has been spilled on the subject, and even G.B. Shaw and G.K. Chesterton participated in a mock trial to try and determine Jasper’s guilt. I cannot recommend this book enough—even more so because it grows on you. (Boze thinks it is secretly my favorite Dickens.) Once you start Drooding, there’s no turning back. –Rach

03. Bleak House (1853)

“Bleak House is the work which most powerfully suggests the darkness of London,” writes Peter Ackroyd, “… a serious London, full of mysteries of the past and mysteries of origin. In all respects it conveys a haunted city, half pantomime-half graveyard, and full of ghosts and unseen presences.” The fog that oozes in from the Essex marshes and lodges in the stems of pipes in the opening paragraphs seems to suffuse the whole book. Here, more than anywhere else, Dickens cements his reputation as a master of atmosphere and description. There’s an energy to the whole affair that, rather like Shakespeare’s Hamlet, suggests a creative genius writing at the height of his powers. —Boze

02. [tied for second] David Copperfield (1850)

There are those—Freud and Tolstoy among them—who think David Copperfield the greatest book ever written. Certainly it brings to a shining perfection the “Dickens plot,” variations of which he had been writing since Oliver Twist. The version presented in this book—the orphaned boy, cruelly beaten by an implacable stepfather and forced to work in a blacking factory before absconding to London in search of a new life—has proven the most influential of all Dickens’s plots, animating the novels of Stephen King, J. K. Rowling and Barbara Kingsolver, among others. And this most autobiographical of all Dickens’s novels also features his best cast of characters. Mr. Micawber, Steerforth, Tommy Traddles, Agnes, Uriah Heep, Aunt Betsey, Rosa Dartle, the man who yells “goroo!”—every character who speaks, even once, is made instantly memorable. There’s a scene towards the end that might be the most emotionally devastating in the Dickens canon. It is my favorite book. — Boze

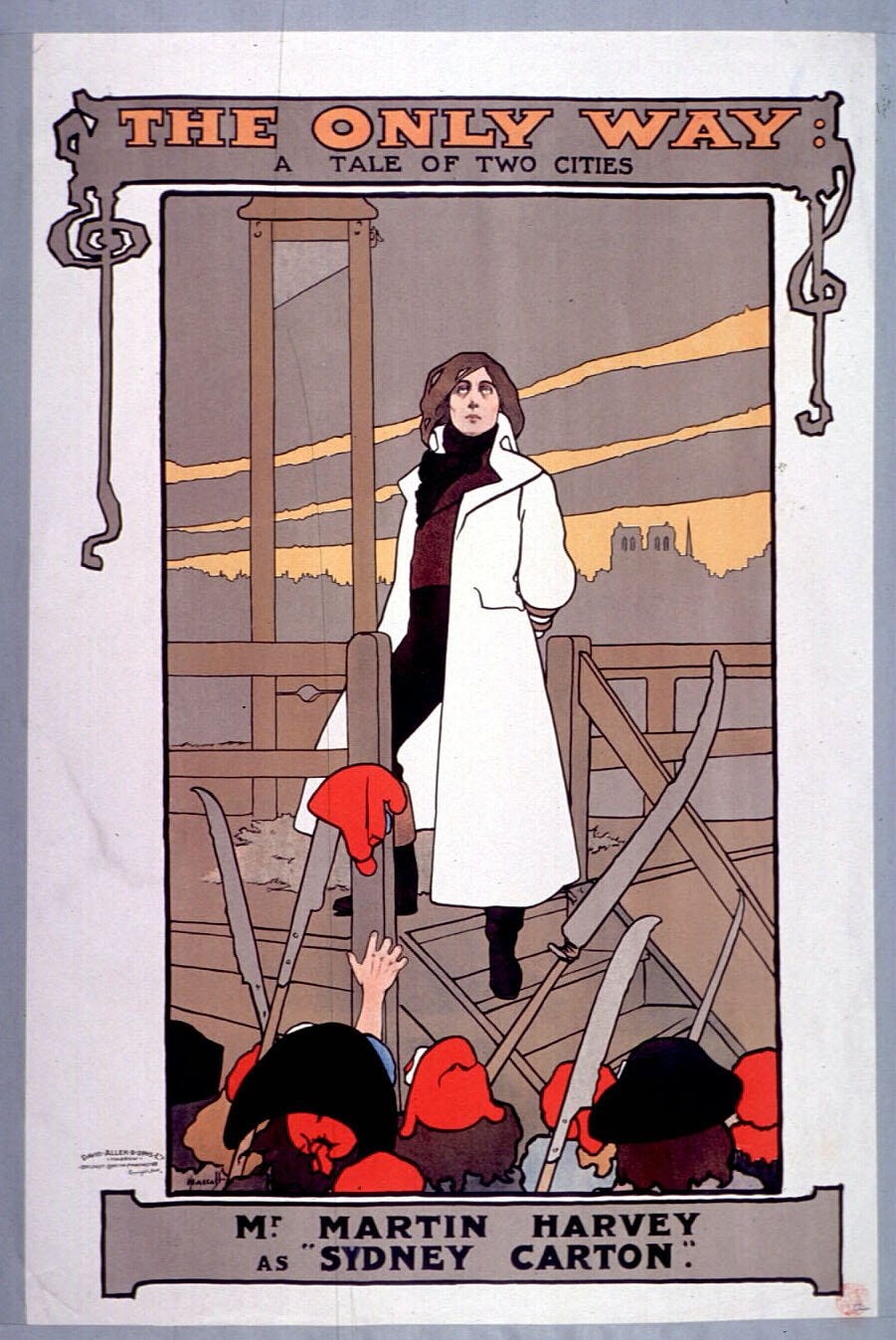

02. [tied for second] A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

The first time I encountered this classic tale of revolution and unrequited love inspired by Thomas Carlyle’s history of the French Revolution, it was with Frank Muller’s atmospheric voice on audiobook, and my life has never been the same since. (I blame everything on Sydney Carton.) It is often argued that the usual Dickens humor is less effective here (looking at you, Jerry Cruncher) and it has one of his less successful leading females. But the perfection of its story and fulfillment cannot be overstated, and Sydney Carton is possibly the greatest fictional character ever, side-by-side with Jean Valjean. Dickens pays off every possible line and motif that he sets up. Madame Defarge is one of the most iconic villains in any novel, and the almost-father-figure of Mr. Lorry remains one of my favorites. A Tale of Two Cities has a melancholy grandeur and timelessness; it feels more like a fairy story, or a parable, that just happens to be set during a very distinctly violent period under the shadow of the guillotine. Like A Christmas Carol, one cannot imagine an alternate timeline in which A Tale of Two Cities hadn’t been written. It is “a far, far better thing.” –Rach

01. The Pickwick Papers (1837)

“Sam Weller and Mr. Pickwick are the Sancho and the Quixote of Londoners, and as little likely to pass away as the old city itself.”

~John Forster

We debated the ranking of the second and third books (before settling on a tie), but there was never any question which would be our joint favorite. Chesterton thought Pickwick, Dickens’ debut novel, the best he ever wrote, “the splendid, shapeless substance of which all his stars were ultimately made.” It is certainly the one Dickens book that can be said to have invented a whole world. The landscape of coaching inns, taverns, village squares and bright May meadows through which Pickwick and friends ramble seemingly without end belongs to an England that may never quite have existed, an England of the mind. In this the book anticipates the great fantasy novels of the twentieth century, many of which use a similar imagined England as their basis (the fingerprints of Pickwick can be seen in Fellowship of the Ring). The Christmas sequence at Dingley Dell may be the most purely pleasurable sequence Dickens ever wrote. Dickens never took as much joy in writing as he did in this novel; indeed, if any book can be joy in book form, it’s this. —Boze

“There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast.”

~ The Pickwick Papers, Chapter 57

Great post! It made me want to start reading Dickens again, so that’s about the highest praise I can give you.

Haha, I love the agreements and disagreements here! Would love to hear everyone else's list of personal favorites--these are subjective, needless to say! Dickens contains multitudes and there is something for everyone 🖤