Every Episode of Agatha Christie's Poirot with David Suchet Ranked, from Worst to Best

A Celebration of All Things Poirot

Agatha Christie did not love Hercule Poirot.

Which is not to say she could get rid of him; indeed, she continued to churn out new Poirot books into her final years. Debuting fully formed, Athena-like, in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), the dapper Belgian detective would feature in 32 subsequent mysteries (and 51 short stories) in a career spanning fifty years. With his pocket watch, patent-leather shoes, green cat-like eyes and (depending on your perspective) endearing / annoying habit of referring to himself as the world’s greatest detective, Poirot acquired a reputation for being effete and big-headed. Though he proved a steady seller, in time she wearied of him. “There are moments,” she lamented in her autobiography, “when I have felt: Why-why-why did I ever invent this detestable, bombastic, tiresome little creature? … Eternally straightening things, eternally boasting, eternally twirling his moustaches and tilting his egg-shaped head … I point out that by a few strokes of the pen … I could destroy him utterly. He replies, grandiloquently, ‘Impossible to get rid of Poirot like that! He is much too clever.’”

If only she could have met David Suchet.

In the late 1980s Mr. Suchet, who had previously played Inspector Japp in the Peter Ustinov television film Thirteen at Dinner (based on the novel Lord Edgware Dies), was invited to lunch with Rosalind Hicks, the daughter of Agatha Christie, and her husband Anthony. During the meal they revealed that ITV was developing a new drama based on the Poirot stories and that they wanted Suchet to play the lead character. Rosalind assured him it was what Agatha herself would have wanted.

Suchet’s commitment to the role became legendary. Before filming began, he read every story featuring the famous sleuth and compiled notebooks on Poirot’s mannerisms, which he consulted during filming. (For a scene in which Poirot prepares tea, Suchet phoned his wife and asked her to find out how many cubes of sugar Poirot takes. She returned with the answer, “Three, or sometimes five.”) It’s said he developed Poirot’s mincing gait by placing a rolled-up newspaper (or, in some versions of the story, a penny) between his legs. Early in the filming of the first season Suchet nearly quit the show after a spat with a director over the question of whether Poirot should set a handkerchief on a park bench before sitting down. “There’s no question he’s obsessive-compulsive,” says Suchet. “It’s not a precious thing. You often hear writers say their characters take over, and Poirot takes over. And that chap can be really irritating.”

But his attention to detail paid off. Seeing him onscreen, even in the first episode, you find it hard to believe that anyone else could ever have dared play Poirot. He seems somehow to have sprung off the page and onto the screen. And in a series that ran for twenty-five years, through changes of producers, the departure of the core cast, and threats of cancellation, Suchet’s performance became the one constant. He’s so good in the role that it’s easy to take him for granted, but in seventy episodes there’s not a single gesture, not a line reading that feels out of place. He so thoroughly inhabits the character that it’s not hard to imagine that in a hundred years, when people talk about Hercule Poirot, they will be picturing David Suchet.

But his is not the only great performance on the show. Indeed, one of the remarkable things about Agatha Christie’s Poirot is how perfectly each of the supporting players—Hugh Fraser as Arthur Hastings; Philip Jackson as the dogged police inspector Japp; and Pauline Moran as Poirot’s mystically inclined but efficient secretary, Miss Felicity Lemon—embody their respective roles. In her first decade as a mystery writer, Agatha followed the “Holmes-Watson-Lestrade” model and the show places those relationships at its center, in the process elevating characters who appeared in the books less often than you might imagine (Hastings only features in eight of the novels, Miss Lemon in four novels and five stories, six if you count the only recently published “Hercule Poirot and the Greenshore Folly.”) The four have an easygoing rapport, abetted by some sharp comic writing; I recently watched the entire series with my family, and on looking back our favorite episodes tend to be the ones that prominently feature the full cast.

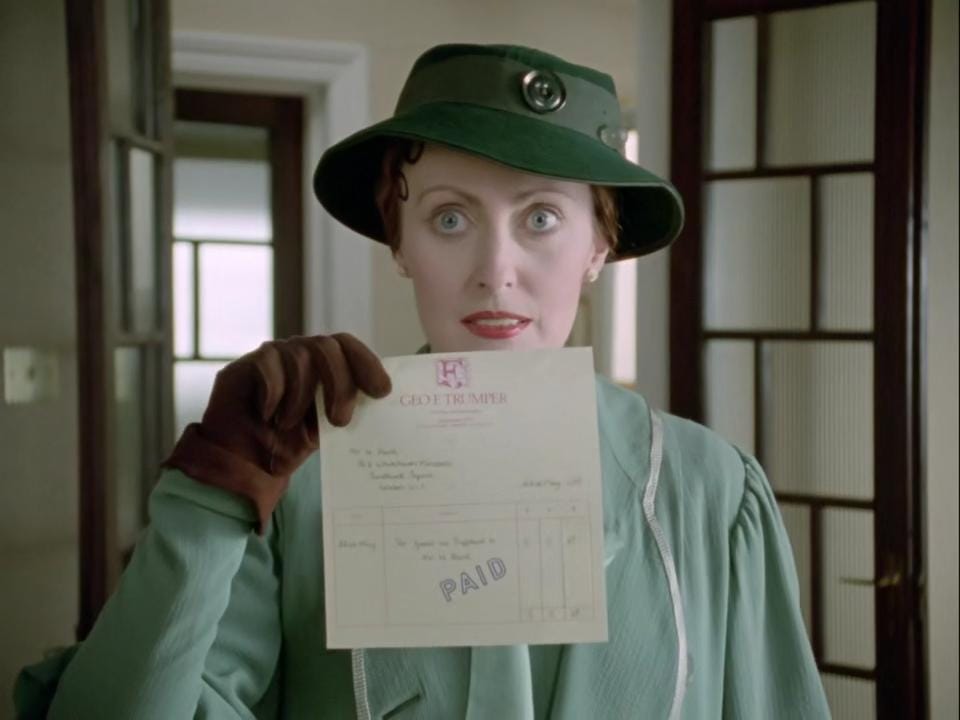

In interviews each of the central quartet have spoken of their affection for one another. “Philip and Pauline were great fun,” says Hugh Fraser, “and we had a lot of laughs on set, it wasn’t all dead serious and hard work. Because a lot of the series was set in the 1930s we’d go to a lot of little-known houses that were not only built in the art deco style but were also furnished in that style still. Sometimes when I had that lovely car to drive we’d be driving along country roads or through the middle of London in the suits and the hat and it did feel glamorous.” When producers Clive Exton and Brian Eastman left the show in 2001, and the new production team of Michele Buck and Damien Tammer announced that Hastings, Miss Lemon and Inspector Japp would be leaving the show, you can sense the barely veiled disapproval of the actors. “They wanted a film noir feeling—which isn’t in the books,” says Pauline Moran, “and guest stars. After Philip and Hugh and I did Evil under the Sun we were shown the door and they didn’t include us in the storylines.” She adds, with icy British politeness, “I’ve mixed feelings about that.”

To celebrate this latest re-watch, I’ve reviewed and ranked every episode of the series, in the process revising and expanding a similar ranking I made ten years ago when I finished Poirot for the first time. You’ll find that I do have a slight preference for the earlier seasons—the dialogue, the characters, that grainy 1980s film aesthetic (some say it’s dated but I find it nostalgic). However, there are some standout episodes from later in the series that number among Poirot’s best hours. And when it came time to pick number one, there was never any question which would be my choice. It is the one episode that always leaves me in tears. It also seems to be the consensus favorite among fans.

70. The Big Four (13.02)

A dreadful adaptation of Christie’s early spy thriller, itself stitched together from a previous collection of short stories involving a sinister band of conspirators who blow up mountains and murder people with electrified chess tables. (Script co-author Mark Gatiss has called the book “an almost unadaptable mess”; Christie herself called it “rotten”.) The screenwriters make a game attempt to keep things grounded, but it feels at times like fan fiction and some of the narrative decisions are baffling: Hastings vows revenge for Poirot’s apparent murder but then vanishes from the story; the murderer dies randomly at a convenient moment. Redeemed slightly by the decision to bring back some beloved characters. The opening scene is the best in the series.

69. The Labours of Hercules (13.04)

Following a devastating professional failure that results in a young woman’s death, Poirot is cajoled into going on holiday in Switzerland, where he’s reunited with the Countess Vera Rossakoff (last seen in season three’s “Double Clue,” here played by Orla Brady). The countess now has a full-grown daughter, Alice, whose presence serves to remind Poirot of the life he might have had. Very loosely based on a collection of a dozen short stories, of which the majority are only glancingly referenced, leaving the viewer wishing this had been adapted as twelve separate episodes in seasons three or four.

68. The Clocks (12.04)

Agatha Christie was uniquely gifted at doing one thing (writing whodunits), and her powers waned when she ventured into other genres; there’s a reason we don’t talk much about the romances she penned under the name Mary Westmacott. She was especially prone to the lure of writing proto-Bond espionage thrillers, such as this in which a young woman arrives at a meeting to find a dead man surrounded by a number of clocks, all of them paused at 4:13. The premise is full of intrigue and the cast—including Anna Massey, Phil Daniels and a young Tom Burke—keep things moving along at a steady clip, but the ultimate feeling, as with the book, is one of frustration.

67. Appointment with Death (11.04)

A weirdly subdued Tim Curry isn’t enough to rescue this desert-set episode, in which Poirot attempts to find the killer of a dissolute archaeologist’s imperious second wife. The script spends far too much time on an ill-conceived expedition to recover the lost head of John the Baptist at the fabled confluence of two rivers, and the many flashbacks of the victim beating her young stepchildren are redundant and jarring. That said, the wide-shot compositions are some of the best in the series, and Paul Freeman (Belloq from Raiders of the Lost Ark) turns up to make a joke about searching for ancient relics.

66. The Lost Mine (02.03)

Mr. Wu Ling, a Chinese-American gentleman, arrives in London to negotiate the transfer of a silver mine to a local bank. However, Ling never arrives for the meeting and his body is later fished out of the Thames. Suspicion falls on a business associate, Charles Lester, whose memories of the evening in question are confused but who recalls stumbling out of an opium den in the East End covered in blood. Some rather obvious disguises and red herrings, though the Monopoly game enjoyed by Hastings and Poirot is a highlight.

65. The Underdog (05.02)

In the short stories, Poirot typically was not acquainted with the victims or their circle before the murder. The show finds ways to incorporate him into the action from the start, and some of the devices by which it does so are, to say the least, implausible. Here, for example, Poirot visits the cantankerous chemist Reuben Astwell to admire his collection of Belgian miniature bronzes just before Astwell is bludgeoned to death. Astwell being notoriously unpleasant, there is no shortage of suspects. Despite having only just watched this one, and having previously seen it on two or three occasions, I had little memory of it apart from the scene where Miss Lemon hypnotizes Hastings into making a hole-in-one.

64. The Adventure of the Western Star (02.09)

Beloved Belgian actress Marie Marvelle consults Poirot about some anonymous letters she’s received threatening the theft of a diamond purchased on the cheap by her husband during a visit to San Francisco. Poirot and Hastings accompany her on a visit to Yardley Chase, the home of Lord and Lady Yardley, who own a diamond identical in all respects to that of the Marvelles. Inevitably, theft ensues and Poirot reveals once again that he can’t be taken in by a clever scheme—though in this case the scheme is implausibly convoluted and the solution self-evident.

63. How Does Your Garden Grow? (03.02)

Poirot attends the Chelsea Flower Show, where a rose is being named in his honor. There he encounters the elderly Ms. Barrowby, who places into his hands a seed packet. Puzzled by her behavior, he arranges to visit her on the following day but learns that she’s died of strychnine poisoning. The most obvious suspect is her Russian maid, Katrina, who—to the surprise of all parties—has inherited the bulk of Ms. Barrowby’s estate. Inspector Japp reveals a surprising knowledge of horticulture. The denouement is very Count of Monte Cristo. Bit of a letdown after the excellent Mysterious Affair at Styles.

62. Triangle at Rhodes (01.06)

In a story that feels at times like a rough draft of Evil under the Sun and Death on the Nile, Poirot’s solo holiday in Rhodes is disrupted by the murder of Valentine Chantry. A vial of strophanthin is found in the pocket of a dinner jacket belonging to Douglas Gold, who had been in love with her. With Hastings still in England, Poirot enlists the support of the fetching Pamela Lyell (Frances Law) to find the origins of the poison. The major problem with this one is that the intricate plot needs longer than the allotted fifty minutes to unfold properly—but of course Christie would recycle the story to better effect elsewhere.

61. The Hollow (09.04)

Poirot underwent a drastic makeover in its ninth season, as new producers came aboard and opted to give the films a more “modern” look in keeping with ITV trends of the mid-2000s. Hastings, Inspector Japp and Miss Lemon are largely absent, taking their comedy and camaraderie with them. This has made the final five seasons controversial among fans, with many preferring the warmth and joy of the earlier outings. But it resulted in some of the best episodes of the series, with season nine being arguably the best of the lot. There’s a thematic thread running through the season of missed chances and lives gone awry, as in this episode centering on a woman who’s found poolside holding a gun over the body of her ostentatiously adulterous husband. But forensic evidence reveals that this gun was not the murder weapon, and Poirot suspects she may be taking the blame for the real killer.

60. The Mystery of the Spanish Chest (03.08)

Lady Chatterton visits Poirot with concerns about her friend, Marguerite, who recently married the much-despised Edward Clayton. Poirot attends a party hoping to glimpse Mr. Clayton, who never arrives. It’s later revealed that he had been hiding in the titular chest, and that someone had stabbed him through a keyhole during the party without being observed. When Hastings notes he only took the case after being “buttered up” by Lady Chatterton, Poirot says, “Do you think it is wrong, Hastings, to enjoy the compliments of the buttering?” to which Hastings replies, “No, but do you have to show it quite so much?”

59. Mrs. McGinty’s Dead (11.01)

James Bentley is convicted of murdering his landlady, an elderly charwoman; the evidence of his guilt is overwhelming. But Superintendent Spence (Richard Hope) thinks otherwise, and seeks Poirot’s aid in finding the real killer before his imminent execution. An attempt is made by a suspect to murder Poirot by shoving him in front of an oncoming train. Meanwhile Ariadne Oliver (Zoe Wanamaker) stress-eats apples and rows with Robin Upward, who is adapting her fictional sleuth Sven Hjerson (an obvious Poirot analogue) for the stage, but insists on sexing up the character. “He’s arriving, dripping with sweat,” says Upward, “having skied the ten miles from the village.” “He’s sixty,” Ariadne replies.

58. The Plymouth Express (03.04)

Adapted from an early story that was later expanded into a middling novel, The Mystery of the Blue Train, in the wake of Christie’s divorce. Mining magnate Gordon Holliday asks Poirot to vet an unsavory young man his daughter, Florence, fancies. She has an ex-husband who’s desperate for cash and a jewel collection that renders her a magnet for ne’er-do-wells. When she’s found dead in a carriage aboard the titular train, Poirot must recover the jewels in the hopes of uncovering the culprit. Another victim of the early third season slump, though better episodes are soon to come.

57. The Incredible Theft (01.08)

A middling mystery involving the German theft of top-secret British naval documents, redeemed slightly by one of Poirot’s best lines. When Mr. Mayfield says, “No need to go into that, Mr. Poirot. Let sleeping dogs lie,” Poirot replies, “No, no, no, Mr. Mayfield. Between the husband and the wife there should not be the sleepy dogs.” Meanwhile, Hastings is obliged to share a bed with Inspector Japp at a local inn, where Japp mumbles things like, “Stand back, lads, he’s got a blancmange” in his sleep. The writers are having fun, the actors are having fun, we’re all having fun.

56. The Million-Dollar Bond Robbery (03.03)

The first episode of the show to be scripted by the great Anthony Horowitz (fun fact: he was brought into the world by David Suchet’s father, a famous gynaecologist) sees Poirot traveling to America aboard the Queen Mary, accompanied by a million dollars in Liberty Bonds which some industrious thieves have been attempting to purloin. Ably demonstrating his knack for adaptation, Horowitz dramatically alters the plot and expands the roles of some minor characters, resulting in a story that places Poirot believably near the center of the action. Features another of those mysterious, flamboyant ladies who is obviously up to no good. Fans of old-timey stock footage will LOVE this one.

55. Problem at Sea (01.07)

While enjoying a sea voyage with Captain Hastings, Poirot must investigate the death of a fellow passenger, the imperious Mrs. Clapperton, found stabbed to death in her cabin. Her longsuffering husband, the affable John Clapperton (who styles himself “Colonel” despite never having seen combat) has a solid alibi for the murder, having been ashore at that hour exploring the bazaars of Alexandria. We’re given our first glimpse of the traumas that Hastings suffered during the war and his fascination with shooting at clay pigeons (“Whatever is the use of me introducing you to nice young ladies,” grumbles Poirot, “if all you do is talk about the shooting of clay pigeons?!”).

54. Cards on the Table (10.02)

An inventive premise that almost tips over into absurdity: four “detectives” (among them Poirot and Ariadne Oliver) are invited to the home of the charismatic Mr. Shaitana (Alexander Siddig). Also present are four people suspected of having committed a crime, but who were never convicted. In the midst of a bridge game, Mr. Shaitana is found dead and it’s up to the four detectives to decide which of the four criminals is the culprit. This one is highly controversial among fans for its changes to the novel, including turning a character who was innocent in the book into a killer. Alex Jennings, Lesley Manville (Magpie Murders) and Honeysuckle Weeks (Foyle’s War) all make welcome appearances.

53. Elephants Can Remember (13.01)

Poirot is importuned to solve a cold case, this one involving the mystery of Margaret and Alistair Ravenscroft, an old married couple who died twelve years before. While out walking one evening along the cliffs near their home, Alistair shot his wife and then himself. Their daughter Celia (Vanessa Kirby), now fully grown and goddaughter to Ariadne Oliver, seeks answers. In a major change from the book, there’s the addition of a present-day murder involving a drowned doctor, and a second killer whose behavior feels more in keeping with a pulp thriller (at one point attempting to shove Celia from a balcony). The solution to the Ravenscroft killings is expectedly heartbreaking, though it doesn’t quite scale the emotional heights of Poirot’s other great cold case.

52. Wasps’ Nest (03.05)

Poirot doesn’t always play the avenging angel. Increasingly as the series goes on he acts as an angel of mercy, bringing consolation to the hopeless and using his mastery of psychology to arrange romantic pairings. This episode finds Poirot in “Father Brown” mode, as he attempts to avert a crime against the self and others. Attending a garden fete at the coaxing of Hastings, he suspects evil is afoot when he meets John Harrison and Molly Deane, a bohemian couple who seem to be having marital troubles. A charismatic artist, Claude Langton (a very young Peter Capaldi), has come between them. Superbly expanded from the short story, with a shockingly bittersweet and affecting denouement.

51. Dumb Witness (06.04)

After suffering a nasty fall from the top of a flight of stairs, spinster Emily Arundell is dispatched via poison one evening, her mouth emitting a ghoulish green liquid that will remind astute viewers of The Hound of the Baskervilles. There are subplots involving an attempt to break the motorboat world speed record and two balmy women who live together and think they can communicate with the spirit of a deceased dog. Mostly you’re just glad to have Hastings and Poirot still working together, as the events of the previous episode made it clear that Hugh Fraser’s departure was imminent.

50. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (07.01)

Poirot, having vacated Whitehaven Mansions and absconded to the village of King’s Abbot to grow vegetable marrows, is called out of retirement by the murder of a local industrialist, stabbed in the back by a Tunisian dagger late one evening in his office. This episode sparked justifiable outrage among fans by making no effort to preserve the central conceit that has made this one of the most celebrated mysteries in the canon, though in fairness to the writers, it’s hard to imagine how that might have been done in a visual format. However, such is the strength of Christie’s plotting in this book that the episode almost works even without that final twist.

49. Third Girl (11.03)

A frustrating adaptation of Christie’s rather plotless late novel, involving a woman who thinks she may have committed a murder but whom Poirot comes to believe is in grave danger. While the script happily excises Christie’s mean-spirited jibes at young women of the 1960s, what it adds doesn’t notably enhance the story. A brief scene from the book in which Ariadne Oliver is being trailed by an unseen assailant becomes an interminable sequence that seems designed to pad out the show’s runtime. However, the final scene, in which Poirot again plays matchmaker, goes further than perhaps any before it in highlighting the loneliness of the man and the things he gave up to become the world’s greatest detective.

48. The Adventure of Johnnie Waverly (01.03)

Marcus Waverly calls on Poirot after receiving a note threatening the kidnapping of his young son. Poirot and Hastings visit Mr. Waverly’s grand country estate but are unable to prevent the abduction. A breezy episode, featuring a priest hole, a suspicious vagrant, and an early glimpse of Hastings’ Jacaranda, which breaks down when the pair visit a village pub in search of a full English breakfast. Docked a few spots for featuring a very obvious culprit, and no murder.

47. Dead Man’s Folly (13.03)

The last episode to be filmed finds Poirot visiting Devon to meet Ariadne Oliver, who’s been assigned the task of organizing a murder mystery fete. Ariadne fears that someone is conspiring to commit a real murder; her fears are vindicated when a child is found dead in the boathouse. There’s an old hunk of a sea dog who seems to have wandered in from Cold Comfort Farm and a rakishly debonair Black man who pilots a sailboat practically onto the grounds, only to be arrested for the murder of a gal who’s vanished and is presumed dead (the Devonshire police apparently being unfamiliar with the legal principle of habeas corpus). Thoroughly enjoyable fare, and if you’ve ever wanted to see Greenway Estate, Agatha Christie’s actual home, this is where it was filmed!

46. The Kidnapped Prime Minister (02.08)

Poirot is summoned to Whitehall when the prime minister suffers an attempted kidnapping, and then an actual kidnapping, on the eve of an international conference. It’s the fanaticism of the principal baddie that sticks in the memory, though this is not enough to rescue this episode, which remains oddly uninspired despite several lively set pieces (perhaps because Hastings is sidelined). This is Christie in thriller mode, an ill-advised choice even in the shorter outings, though the method of kidnapping the titular PM is quite clever.

45. The Mystery of the Blue Train (10.01)

A much-improved version of the story filmed previously as “The Plymouth Express.” When Ruth Kettering is murdered aboard a train, Poirot suspects she may not have been the intended victim. Kettering had swapped carriages with Katherine Grey (Georgina Rylance), a timid heiress with the air of Joan Fontaine’s character in Rebecca (1940). Nicholas Farrell, James D’Arcy, the late Roger Lloyd Pack and Elliot Gould (as Ruth’s industrialist father) all feature in this lush and fleet-footed film, though the real standout is Alice Eve as Lenox, who takes on the role of Katherine’s companion and protector when it becomes clear her life is threatened, and whose spirited response to a burglar resulted in cheers and applause from my whole family.

44. The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman (05.05)

In keeping with the show’s mandate to provide more material for Pauline Moran, season five even gives Miss Lemon a love interest—a slightly shady valet who happens to have been working for an Italian count whose murder Poirot is investigating. Hastings is involved in another of those “world’s slowest car chases” and we get this fun bit of back story:

Poirot: Hastings, have you never exaggerated your own importance in order to impress a young lady?

Hastings: Most certainly not! Well, I once told a girl I was a member of Wentworth when I wasn’t, but she didn’t play golf anyway. She thought Wentworth was a lunatic asylum.

43. After the Funeral (10.03)

When Mr. Richard Abernethie dies of natural causes, his estate is divided between his surviving relatives. During the reading of the will, his sister Cora provokes much hubbub and uproar by saying he was murdered. On the following day, Cora is found bludgeoned to death in her bed. Not long after, Cora’s companion, Miss Gilchrist, is nearly killed by a slice of poisoned cake. One actress whom I shan’t name delivers an impressively unhinged performance, looking and behaving rather like an Irish banshee in black bombazine, though the full scope of her acting only becomes clear on repeat viewings. Michael Fassbender, dapper as ever, turns up in an early role.

42. The Mystery of Hunter’s Lodge (3.11)

Hastings and Poirot partake in a weekend hunting expedition. Poirot hopes to bag a grouse that will furnish an exotic meal to be cooked at the local hotel, but succumbs to sickness and is soon confined to bed against his will. Meanwhile the owner of the lodge, Harrington Pace, is gunned down in his second-floor study and everyone has a motive. Dodgy disguises and mysterious housekeepers abound in this pleasantly rural outing, and Suchet mines much comedy from Poirot’s melodrama. “Mon Dieu! Look at this, Hastings!” he cries. “I am a corpse waiting to die. I shall not survive to enjoy my tetras a l’anglois!”

41. Hallowe’en Party (12.02)

Christie’s 1969 novel, one of her last, is not beloved in the Poirot fandom. The Mark Gatiss-penned adaptation, which leans into the seasonal atmospherics, is a considerable improvement. Ariadne Oliver attends a Hallowe’en party at which a thirteen-year-old girl, Joyce Reynolds, claims to have once seen a murder, though she didn’t realize it was a murder until much later. Later that same evening she’s drowned in a tub while bobbing for apples. In keeping with the more religious tenor of the later seasons, Poirot insists that “Hallowe’en is not a time for the telling of the stories macabre,” but the film itself argues against him, with its garish jack-o-lanterns, moldering leaves and elaborate gardens concealing foul crimes. Mandatory autumn viewing, stylish and clever.

40. Murder on the Links (06.03)

Traveling in France, Poirot encounters one of his most bizarre and byzantine cases when a man is found murdered near the site of a grave he had been in the process of digging. There’s some good-natured contretemps between Poirot and a pompous, pipe-smoking local police inspector who resembles G. K. Chesterton (and who is about as French as Winston Churchill), but the real highlight of the episode is Bella Duveen, a sultry, sad-eyed stage performer whose sudden emergence in Hastings’ life portends a parting of the ways for our three leads. The moment when Hastings sees Bella for the first time is beautifully acted by Hugh Fraser. (There’s also a terrific sight gag when Hastings assures Poirot that he’s not there to play golf, right as they pull up to the Hotel du Golf.)

39. Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan (05.08)

On holiday in Brighton, Poirot is drawn into intrigue when a pearl necklace that’s lately come into the possession of Mr. Opalsen is stolen. Opalsen had planned to show off the necklace as a prop in a stage play, wrongly thinking he could prevent it from attracting unwelcome attention. While the mystery is fairly rote, there’s a fun subplot in which a newspaper offers ten guineas to readers who spot a man named “Lucky Len” wandering through Brighton, a man who, as it happens, looks remarkably like Poirot. A weird running joke with a fantastic payoff.

38. Taken at the Flood (10.04)

Arguably this is the episode that most improves on second viewing. Controversially, the writers have taken Christie’s rather sedate novel about the death of Gordon Cloade and the effects of that death on loved ones and transformed the baddie into a sneering serial killer who gleefully induces abortions and blows up estates with dynamite. While I tend to lament attempts to “sex up” the Poirot novels, I think these changes work for the most part. It’s not really Christie, but it’s fun. What keeps the episode hanging together is Elliot Cowan’s dynamic performance as David Hunter, in a role that should have brought him more attention. Cowan is almost hypnotically watchable, and delivers what is probably the single most memorable turn by a guest actor in the whole series.

37. The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb (05.01)

A British archaeological expedition opens a pharaoh’s tomb in Egypt, and soon everyone involved is being dispatched. Is it a curse, or something more sinister? Poirot and Hastings, newly returned from abroad, are on the case. The show starts giving Miss Lemon more to do in season five and, as will become typical, she gets the episode’s best moments: attempting a séance with Hastings, revealing that her recently deceased cat was named Catherine the Great because it liked to sleep in the fireplace, and this exchange between her and Poirot:

Miss Lemon: I could say “biog.” Instead of “biographical,” I could say “biog!”

Poirot: Is that a word, Miss Lemon?

Miss Lemon: It sounds efficient. I heard someone say it in a picture. “Gimme da biog on Dutch Schultz, Miss Longfellow.”

Poirot: “Biographical material” will do very nicely, thank you, Miss Lemon.

36. One, Two, Buckle My Shoe (04.03)

Poirot’s dentist, Mr. Morley, is found dead in his office with a bullet wound to the head. When Mr. Amberiotis, who had been for a cleaning that morning, dies of a Novocaine overdose, the police suspect Morley accidentally killed him and then took his own life. However, the mysterious disappearance of a woman whom Poirot had seen outside the clinic on the morning of Morley’s death suggests an altogether more diabolic scheme is afoot. The writers make a game attempt to streamline one of Agatha’s three or four most knotted whodunits, though even alert viewers may find themselves confused by the solution. The absence of Hastings is keenly felt; luckily a blustery young Christopher Eccleston turns up to keep things lively.

35. The Third Floor Flat (01.05)

Confined to his apartment with a cold, Poirot eagerly accepts Hastings’ invitation to see a murder mystery play at the theatre. Three young people who reside in Whitehaven and also attended the play enlist his aide when they inadvertently enter the wrong flat and discover a dead body. “You’ll be having murders in your back bedroom next,” grumbles Inspector Japp, while Poirot provides a rare peek into his own past: “You know, Mlle. Patricia, I once loved a very young, beautiful English girl who resembled you greatly. But alas, she could not cook. And, the relationship withered.”

34. Murder in the Mews (01.02)

Poirot investigates the death of a woman murdered in Bardsley Mews on Guy Fawkes Night, the shots muffled by the clamor of fireworks. In only the second episode, already the lead actors inhabit their roles as though they’ve been playing the characters for twenty years. Hastings is surprised to learn that saying “Him collar no very good starchy” means nothing to his Chinese launderer, while Inspector Japp has a memorable exchange with a street urchin who seems to have wandered in from Oliver Twist. When he offers this “bright kind of shaver” a sixpence, the boy replies, “You couldn’t see your way to making it a shilling, could you?”

33. The Dream (1.10)

Poirot meets Benedict Farley, a pie manufacturer, following a series of dreams which Farley reads as premonitions of his own death. Shortly thereafter Farley dies, seemingly by his own hand, but Poirot is skeptical given how keen the man was to continue living. A first-rate early episode in which Poirot and Miss Lemon wrangle over his tisane schedule and Poirot informs Hastings, “To say that Benedict Farley makes pies is like saying Wagner wrote semi-quavers!” (They’re “horrible” but “there are a great many of them.”) This was that period of the show where the writers hadn’t yet figured out how to vary their denouements, so every episode ends with a chase.

32. Double Sin (02.06)

It isn’t hard to guess the solution to the mystery, which involves a stolen suitcase full of Napoleonic-era medallions. What makes this one worth watching is that Poirot and Hastings are, once again, headed to the Lake District, where they meet a young woman named Mary Durrant (Caroline Milmoe), a style icon. Poirot is threatening retirement after a falling out with Inspector Japp, and the resolution to their row yields one of the more affecting moments in the series.

31. The Disappearance of Mr. Davenheim (02.05)

After a brief conversation with his wife, banker Mathew Davenheim puts on the 1812 Overture, steps out of the house—and disappears into a fog. Hastings takes over the investigation after Poirot makes a bet with Japp that he can solve the case without leaving his flat for a week. Keen to keep the grey cells in good order, he begins learning magic and is given a parrot for company, leading to this classic exchange:

Poirot: And please, do not fraternize with that creature. I am still training him.

Hastings: It’s only a parrot!

Poirot: I was talking to the parrot.

30. Four and Twenty Blackbirds (01.04)

Whilst dining out with his dentist, Poirot is perplexed by the behavior of an old man who orders the same foods at each meal—except on this occasion, when he breaks from routine by ordering a blueberry pie. When the man is later found dead at the bottom of a flight of stairs, Poirot’s investigation draws him into London’s art world, where he meets an unscrupulous agent and a nude model who, naturellement, briefly catches Hastings’ fancy. Satisfyingly intricate, with one subtly deployed clue whose cleverness grows with each viewing.

29. The Adventure of the Clapham Cook (01.01)

A fine introduction to Japp, Hastings, Miss Lemon and our favorite Belgian detective, involving a disappearing cook, a bank clerk and an old trunk. Katy Murphy (Jenny Wren in Our Mutual Friend ’95) plays a good-natured parlormaid who seems to have a crush on Poirot, while a young Danny Webb turns up as a sneering Cockney. The search for the cook leads Hastings and Poirot to the Lake District via train, where Poirot makes his views on the landscape known. “Look at it, Hastings. Not a building in sight. Not a restaurant, not a theatre, not an art gallery. A wasteland!”

28. The Double Clue (03.07)

“In my experience I have known of five cases of women murdered by their devoted husbands,” says Poirot early in this episode. “And twenty-two cases of husbands murdered by their devoted wives.” Yet the Belgian bachelor is not wholly immune to the charms of women, as this episode demonstrates. For here, in the figure of the Russian emigré Countess Vera Rossakoff, Poirot meets his Irene Adler. Anthony Horowitz pens this sweepingly romantic episode that features a pre-Mr. Collins David Bamber, yet another attempt by Hastings and Miss Lemon to play detectives and one of Christopher Gunning’s best scores.

27. The Affair at the Victory Ball (03.10)

“They seek him here, they seek him there, those Frenchies seek him everywhere!” cries Hastings early in this episode. It’s the night of the Victory Ball and everyone is expected to attend as someone famous. Hastings goes as the Scarlet Pimpernel; Poirot goes as himself. A party of six dresses as characters from the Commedia dell’arte. By morning two of them are dead. Poirot ingeniously uses a live BBC Radio broadcast (and a rather clever subterfuge) to catch the killer. An expertly clued mystery with a worthy finish.

26. Hickory Dickory Dock (06.02)

In which we learn that Miss Lemon has a sister, Mrs. Hubbard, who runs a student hostel. She seeks Poirot’s assistance in finding the thief who has stolen a string of apparently random items—light bulbs, boracic powder, a ring, etc. The good-natured if slightly timid Celia Austin confesses to some of the thefts, but is later found murdered in her bedroom. Memorable for its deeply unnerving baddie and a devilish method of giving oneself an alibi. Equally memorable (though not in a good way) for a children’s choir shrieking “HICKORY! DICKORY!” seemingly without end. Inspector Japp naively rinsing his face in Poirot’s bidet might be the single funniest moment in the series; reader, I screamed.

25. The Mysterious Affair at Styles (03.01)

It took three seasons for the show to adapt Christie’s first novel, written in response to a dare from her sister and showing off the impressive knowledge of poisons she’d acquired whilst working as a nurse in the war. This episode reveals, at last, the origins of Poirot’s friendship with Hastings. Poirot is a refugee, having lately fled Belgium, while Hastings, invalided from the front, watches newsreel footage with an air of quiet disbelief and repressed shock. When the owner of the house in which he’s living, Emily Inglethorpe, is murdered, suspicion falls on her much younger husband, Alfred. The script satisfyingly conveys the intricacies of Christie’s plotting, though what makes this one memorable is the instant friendship between the lead trio, and the first (but not the last) instance of Hastings falling in love.

24. The Tragedy of Marsdon Manor (03.06)

Poirot visits Marsdon Leigh at the behest of a village innkeeper who had written to say he needed help. Poirot is not pleased to learn that the innkeeper is a mystery novelist, and needed help thinking of an end to his book. But dark deeds are afoot at the local manor home, where Mr. Maltravers has recently passed on. Ghosts are said to roam the property and his wife thinks he died of fright. A wonderfully Gothic episode featuring a wax museum, a clever late-in-the-game ruse by Poirot, and an inn where the duck-feather pillows “have the little ducks still in them.”

23. The Chocolate Box (05.06)

In a story told almost entirely in flashback, Poirot recalls his greatest professional failure, the case of a murder he investigated while working in the Belgian police force. Ambitious young politician Paul Deroulard died of apparent heart failure, but Poirot, acting against his superiors, insists he was poisoned and resolves to learn why. He does learn why—and the answer to the mystery of why the case was never solved will break your heart. Featuring Anna Chancellor (Caroline Bingley from the 1995 Pride and Prejudice) as an old flame of Poirot’s, this one got a rapturous reception when I showed it to my in-laws. A beautifully staged episode with an aftertaste that is bittersweet.

22. Murder on the Orient Express (12.03)

A stellar cast—Toby Jones, Jessica Chastain, David Morrissey—anchors this bleak and claustrophobic adaptation of Christie’s oft-adapted novel. The writers make the sensible choice to emphasize Poirot’s Catholic faith and hunger for justice, resulting in a climactic crisis of conscience that represents a notable (but welcome) departure from the book, which ends in an oddly breezy and abrupt fashion. In the process, the episode becomes in its best moments a character study of Poirot himself.

21. The Yellow Iris (05.03)

Adapted from a short story that Christie would later expand into the non-Poirot novel Sparkling Cyanide, centering on a woman’s murder at a restaurant in Argentina two years before—a murder that Poirot never solved because he was obliged to leave the country in the wake of political upheaval. Now the victim’s husband is hosting a dinner in London to commemorate the anniversary, and has invited all who were present on the night of her death. An eerie, elegiac episode about the power of past events to cast long shadows into the present.

20. Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (06.01)

Notorious miser Simeon Lee invites his grown children to spend the holidays at Gorston Hall, provoking much dismay when he announces he intends to make changes to his will. On the evening before Christmas a hideous, inhuman scream is heard from his room, accompanied by the sound of crashing furniture. The family enters to find him in a pool of blood, his throat having been cut. Lee is one of Christie’s more satisfyingly wicked victims, an unrepentant Scrooge who shamelessly hits on his granddaughter and refers to his diamonds as “my pretties.” Features some excellent clueing and misdirection, but overall a rather chilly adaptation, lacking any sense of festive merriment—much like the book itself, in which the Christmas setting felt incidental.

19. The Case of the Missing Will (05.04)

In a story that almost feels like a backdoor pilot for a show about a plucky girl detective, Poirot investigates the murder of Andrew Marsh, a terminally ill gentleman with dim views of the female struggle for equality who surprises everyone by announcing that he’s leaving his fortune to his ward, the young and precocious Violet Wilson. However, he’s killed before he can pen the new will and it’s up to Poirot, with the assistance of a game Miss Lemon, to uncover secrets that have been hidden for twenty years. There’s something wonderfully Dickensian about this tale of contested legal documents and unexpected lineage, and no other episode more fully explored the power that women have for good or ill.

18. The Adventure of the Cheap Flat (02.07)

Poirot is drawn into intrigue when some friends of Hastings purchase a first-floor flat for eighty pounds, a flat that has refused every other would-be tenant. This is an especially stylish episode, with its Art Deco night clubs, sultry torch singers, and treacherous femme fatales who whisper, “Good night, loverboy!” as they dispatch a too-trusting boyfriend. While posing as a journalist for the Ladies’ Companion, Miss Lemon offers some very quotable wisdom: “Anyone who claims to have been stag-hunting in the Bois de Bologne has been seriously misinformed about life on the continent.” This episode also sees the first appearance of Inspector Japp’s hilariously conspicuous secret surveillance van.

17. The Veiled Lady (02.02)

After boasting to Hastings that he would make a master criminal, Poirot seizes his chance when he encounters a young woman named Lady Millicent Castle Vaughan, who needs him to retrieve some compromising letters hidden in a Chinese box. After deducing the location of the box, Poirot and Hastings mount a home invasion (in full criminal garb) and are summarily nabbed by the police. From beginning to end this is the funniest episode of the show, though the best moment, as usual, belongs to Inspector Japp. “Nobody knows his real name,” he informs a fellow policeman as he bails Poirot from jail. “But everyone calls him ‘Mad Dog.’”

16. The Theft of the Royal Ruby (03.09)

AKA “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding.” Slightly more festive than that other Christmas episode, this one sees Poirot staying at the Lacey family home for Christmas (in the same white modernist house we’ve seen at least once already), investigating the theft of a ruby that was stolen from a crown prince. Some children contrive to stage a murder, hoping to fool the unfoolable detective. Fun fact: Poirot says “a prince” once taught him how to peel a mango—a sly nod to a real-life dinner with Queen Elizabeth in which her husband peeled a mango for David Suchet. Thereafter whenever they saw each other, Prince Philip would say, “Ah, Mango Man.”

15. Murder in Mesopotamia (08.02)

Mrs. Louise Leidner is murdered on an archaeological expedition in the deserts of Iraq, her head bashed in. After the death of her first husband, Frederick, in a train crash, she received menacing letters anytime she showed interest in another man. Just a few weeks ago, the letters began to arrive again. Poirot must unmask the identity of this anonymous correspondent in a mystery that is notorious for a resolution that’s deemed preposterous by many. But if you’re able to suspend disbelief, this is a terrifically chilling and disturbing episode. (Fair warning: there is a murder by hydrochloric acid ingestion that my wife found profoundly upsetting.) I’m not typically a fan of episodes set in the desert, but the air of dread that imbues every frame of this one makes it worthy of acclaim.

14. Three Act Tragedy (12.01)

A standout episode from Poirot’s penultimate season, centering on two seemingly unrelated murders taking place at two parties sharing some of the same guests. Kimberley Nixon is utterly winning as “Egg” Lytton Gore, a vivacious young woman in love with a much older man, though it’s Martin Shaw’s performance as aging thespian Sir Charles Cartwright that makes this a uniquely pleasurable episode. Shaw is by turns cantankerous, charming and wholly sympathetic, a stage idol in winter looking back in remorse on roads not taken, and his ability to portray the varied and ever-shifting facets of Cartwright’s personality elevates what was already one of Christie’s better Poirot stories.

13. Sad Cypress (09.02)

Elinor Carlisle is in trouble. On trial for murder, she faces hanging for the deaths of her wealthy aunt, Laura Welman, and Mary Gerrard, a young woman she resented for having stolen her fiancé, Roddy. Mary collapsed and died while eating lunch with Elinor, an apparent victim of morphine overdose. Poirot has only days to clear Elinor’s name before she’s sentenced to death. Gorgeously filmed but suffused with melancholy, painting a bleak portrait of a relationship dissolving as a result of one man’s choices. Making Mary deeply unsympathetic (a change from the novel) only heightens the poignancy of Elinor’s suffering; the viewer can’t help but wonder why anyone would leave her. Elizabeth Dermot Walsh, like Rachael Stirling in the previous episode, brilliantly portrays the anger and grief of a wronged woman facing death. David Suchet has called this his favorite performance by a guest actor in the whole series.

12. The ABC Murders (04.01)

This stellar adaptation of a fan-favorite Poirot novel follows Alexander Bonaparte Custard (Donald Sumpter), a troubled young man with a habit of blacking out and waking to find that a murder has been committed in his vicinity. Poirot receives a series of cryptic letters from the mysterious “A. B. C.,” an apparent maniac who’s going through the alphabet killing people with alliterative names. The two threads of the story come together beautifully during a conversation between Poirot and a suspect in jail that ranks among the series’ best moments. (It is one of Suchet’s favorites.) Immeasurably better than the “gritty” John Malkovich serial from 2018; good writers know that including humor in a story (in this case, a lovely running joke involving a stuffed caiman that Hastings bagged in Venezuela) only heightens its darker elements.

11. Death on the Nile (09.03)

Simon Doyle and Jacqueline de Bellefort were once engaged; but then the glamorous Linnet Ridgeway (Emily Blunt), whose voice, as Fitzgerald said, was “full of money,” swept in and stole him away. Now the newly married Linnet and Simon are attempting to enjoy a honeymoon cruise down the Nile, but are stalked at every turn by a vengeful Jacqueline. Poirot senses murder in the air but is powerless to stop it. Though the pacing is slightly marred by some scenes that could have been cut, this is a sublimely sinister film that capably channels the tragic nature of its source material. I can never resist an episode that ends with grainy footage of doomed lovers dancing together in better times, and the perfection of those final five minutes makes this one of the greats.

10. Lord Edgware Dies (07.02)

Horowitz scripting, the whole gang together again for one of their final outings—what more could you want? Jane Wilkinson, Lady Edgware, is suspected of murdering her husband after she’s witnessed, by several people, entering their home and killing him. The only trouble is, she was seen by several dozen others at a party being held across town at that precise moment. Seasons seven through nine were the show’s peak, as it leaned into darker, more stylish and more cinematic aesthetics without the gratuitous story changes or showy camerawork that oft marred the final seasons. Notably, there’s a clue late in this episode that I consider one of the cleverest, if not the cleverest, clues in the Christie canon.

09. The King of Clubs (01.09)

Actress Valerie St. Clair (Niamh Cusack), who is engaged to be married to a crown prince, is embroiled in scandal when she turns up at the home of an abusive film director and finds him dead. Fearing that she’ll be accused of the murder, she employs the help of Poirot, who puzzles over the strange events of the night in question when a visibly shaken Valerie was taken in by a neighboring family as they played bridge. Beautifully twisted and profoundly moving, this is the best episode of Poirot’s first season.

08. Dead Man’s Mirror (05.07)

At auction Poirot loses a bid on an antique mirror to the gregarious art collector Gervase Chevenix (Iain Cuthbertson). Shortly thereafter Chevenix is found dead in his study, a bullet from the pistol in his left hand having apparently shattered the mirror behind him. Suspicion falls on his adopted daughter, Ruth, who had recently married in secret against his wishes. A highlight of this Horowitz-penned episode is Vanda, Mr. Chevenix’s wife, a middle-aged lady with a spiritualist bent who’s convinced that she’s the reincarnation of an ancient Egyptian. Jeremy Northam and the always welcome Richard Lintern turn up in supporting roles. The best of the shorter episodes, with one exception.

07. Death in the Clouds (04.02)

Another oft-overlooked episode that earns its ranking by being a pure joy to watch. On a flight from Paris to London, the wealthy moneylender Madame Giselle is found dead. An examination of the scene yields the conclusion that she was murdered by a poisoned dart; however, the cabin was full and at no point could the murderer have blown the dart without being witnessed. As Poirot questions the passengers, a mysterious woman turns up at the local police precinct claiming to be Madame Giselle’s daughter. Hugh Fraser is missed but Jenny Downham leaves an impression as Anne Morisot, whose ambiguous motives and fondness for disguises seem calculated to mislead the viewer.

06. The Cornish Mystery (02.04)

At its heart, Poirot in the early seasons is a study of male camaraderie. Hastings, Poirot and Japp embody a kind of unshowy brotherly affection that’s rare to see on television. All three are at their best in this standout outing, which takes them via train to the fictional Polgarwith in Cornwall to investigate the murder of a woman who suspected she was being slowly poisoned by her husband. Poirot offers some psychological insight into the minds of “les femmes,” while Hastings explains the meaning of the word hussy: “It’s a woman who’s… no better than she ought to be, kind of thing.” Impeccable rainy-day viewing.

05. Peril at End House (02.01)

While on holiday in South Devon, Poirot encounters a young heiress named Nick Buckley (Polly Walker), who has recently been the target of several attempted murders. When Nick’s friend Maggie is murdered at End House during a fireworks display, Poirot concludes Nick was the intended victim. This is perhaps the quintessential Poirot episode, featuring a grand house, a flamboyant performance from the lead actress, an especially devious method of misdirection, some excellent character beats—Poirot refusing to eat his eggs because “they are of totally different sizes”—and the platonic ideal of a final scene, in which the whole gang eats ice cream on the beach. C’est magnifique.

04. Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case (13.05)

In 1949, newly widowed Hastings and a wheelchair-bound Poirot return to Styles, the site of their first mystery, to pursue Poirot’s greatest foe, a murderer who employs psychology to commit crimes that can never be prosecuted. Poirot’s wits are tested to their limits in an episode that induces more gasps than perhaps any other. Written during World War II when Christie feared she might be killed, and kept in a vault for over thirty years, Curtain serves as a lyrical sendoff for her most beloved character, and this film leans into the melancholy, from the motif of Chopin’s “Raindrop” prelude to Poirot’s final words, which serve as a fitting summation of a twenty-five-year’s journey. “They were good days. Yes, they have been good days.”

03. Evil Under the Sun (08.01)

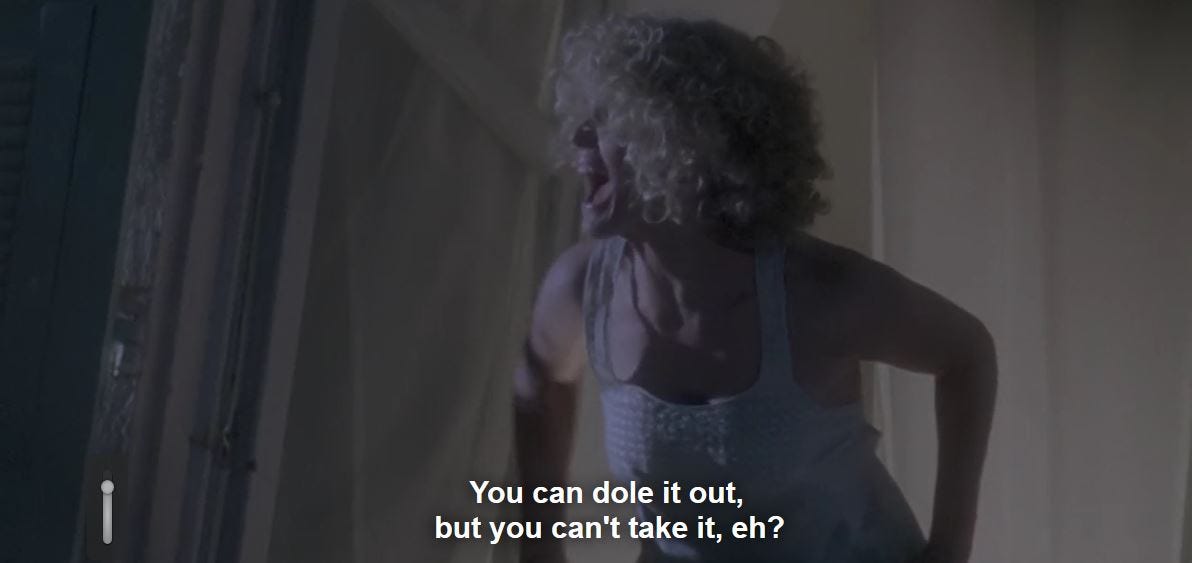

When Hastings returns from Argentina to oversee the grand opening of a restaurant in which he had invested, Poirot suffers an apparent heart attack in the middle of dinner. He reluctantly goes on holiday in south Devon after his doctor declares him “medically obese.” There he becomes embroiled in a row between the longsuffering Christine Redfern and her wayward husband, Patrick, who has been conspicuously pursuing a beautiful actress, Arlena Marshall. When Arlena is found dead on the beach, having been strangled by a pair of powerful hands, Poirot uncovers a scheme that is almost sickening in its brazenness and intricacy. Horowitz inserts some moments of levity but otherwise faithfully adapts the plot of the novel. Christie typically reserved her most disturbing plots for her standalone novels—And Then There Were None, Endless Night. This is Poirot’s most twisted case.

02. Cat among the Pigeons (11.02)

The Mark Gatiss-penned adaptation of Christie’s classic boarding school novel centers on a series of murders at Meadowbank, a school for girls helmed by the formidable Ms. Bulstrode (Harriet Walters), who’s nearing retirement. After a pilot, Bob Rawlinson, dies with guns blazing alongside his best friend, the Prince of Ramat, his niece Jennifer finds herself stalked by shady figures keen on retrieving some jewels that had gone missing at the time of the prince’s death. One of the best-looking episodes of the series, with a visual style that seems designed to evoke the later Harry Potter movies (a feeling that’s enhanced by the presence of Katie Leung in a minor role). Anton Lesser, perhaps the best character actor currently living, plays a police inspector whose initial distrust of the dapper detective gives way to grudging admiration, thereby answering the question every mystery-lover has asked at some point: “What if Chief Superintendent Reginald Bright met Hercule Poirot?”

01. Five Little Pigs (09.01)

Regrets. We all have things in our past that we’d give anything to do over, which is what makes stories of time travel perennially appealing. It’s also at the core of the murder mystery genre—murderers are typically driven to kill because their life has gone awry in some way and they hope to fix it, in the process forever ruining the lives of others. Christie trafficked in mistakes and ruined lives throughout her career, but never more directly or with more feeling than in this, her finest novel.

Lucy Crale’s parents died when she was a child. Her father, Amyas (a pre-Game of Thrones Aidan Gillen), was a philandering artist who gave up the ghost on a warm summer’s day after drinking a bitter-tasting glass of cold beer given to him by his wife, Caroline (Rachael Stirling), as he stood painting by the lake. Convicted of the murder, she died in prison, though not before writing Lucy a letter insisting upon her innocence. Lucy begs Poirot to uncover the truth about who really murdered her father. Moved by her pleas, he interviews five people who were present at the villa on the day of Amyas’s death (the “five little pigs” of the title), sifting through the Rashamon-like narratives in search of evidence the police may have missed.

There’s no aspect of this production that doesn’t work. Handheld cameras are deployed during the flashbacks to lend a sense of immediacy. The camera transitions seamlessly from a room shown in the past to the same room, cheerless and empty, in the present day. Satie’s “Gnossiene No. 01” serves as a leitmotif, and is now so indelibly linked with the Crales that I can never hear it without thinking of poor, doomed Caroline. Rachael Stirling is by turns angry, anguished, shattered and resigned in what is one of the series’ best performances, irresistibly sympathetic even when suspicion of guilt lingers, but Marc Warren, Toby Stephens and Gemma Jones, each playing characters who loved Caroline and Amyas in their own ways, underscore a sense of wounds that can never be mended, even after sixteen years. “It was as if they hadn’t died at all, but I had,” says one character, and as the story nears its end, the effect of the whole—decisions made in haste, acts of cravenness and cruelty and unthinkable courage—is overwhelming. To call it merely the best episode of Poirot is to undersell its achievement. It belongs on any list of the best episodes of television ever made.

Boze, this is an incredible Resource, not just for Agatha Christie fans, but for mystery writers everywhere!

This was so much fun to read and I got more and more excited as I scrolled because Cat Among the Pigeons is among my favorite of the adaptations. Harriet Walter could film a trip to the grocery store and imbue it with meaning, purpose and beauty. I almosts cheered when you had it at #2!