Boze's Eighty-Five Favorite Books of All Time

Hoarded Gems from a Lifetime of Reading

It has been a great joy to spend the past week revisiting and ranking my favorite books from thirty years of reading—the mysteries, fantasies, children’s books, essays, diaries, folklore anthologies, poems, epics and sacred texts that have made me who I am.

First, some warnings and rules. When I started making this list, I resolved to rank only works of fiction. I stuck to that… mostly. I’ve been reading more nonfiction as I get older (one of those unexpected tasks you find yourself doing as a writer), and there are a rare handful of books I would rank alongside the best novels I’ve read. That’s why you’ll see biographies of the Beatles and Dickens and memoirs of English country life on this list. (It occurs to me even as I write this that I should’ve included Laurence Miles and Tat Wood’s About Time, a nine-volume, multi-million-word series on the history and making of Doctor Who. Perhaps on the next list.)

I struggled with how to rank the Bible and Shakespeare—if I ranked the various books and plays individually, they would take up half the list; if I ranked them both as a unit, they would approach the top spots. At last I compromised by listing my favorite sections from each.

Lastly, it should go without saying: this is not an endorsement of every author listed, nor of every idea expressed within each book. Please don’t email me indignantly because you found some offensive statements in Watership Down. I know that not every book is perfect; they were written by human beings. Messy, sometimes deranged human beings. And thank God for that.

Having said all that… here’s the list. Based on my choices here, please suggest more books you think I’d enjoy. As my wife can tell you, I am always looking for new things to read.

85. Crooked House, by Agatha Christie

A wickedly clever standalone mystery involving the murder of Aristide Leonides, the aging head of a very strange family. Christie said this was her favorite of all her books, and you can see its influence on everything from Knives Out to the Flavia de Luce books.

84. Paradise Lost, by John Milton

While I’m not a massive fan of the story—one can’t help wishing Milton had gone with his initial plan to write an epic about King Arthur—it’s hard not to be dazzled by the sheer majesty of the language, and by the infernal cunning of the doomed Satan.

83. Essays, by Michel de Montaigne

Love him or hate him, Montaigne is a terrific hang. On the list of “early modern writers you’d like to grab a beer with,” his only competition is Pepys. Thoroughly secular but endearingly open-minded (he’s skeptical of miracles but doesn’t like to rule out the possibility entirely), his essays offer frank wisdom on humility, sleep, life after death, and the strange case of a famous medieval imposter.

82. The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, by Laurence Sterne

“Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;—they are the life, the soul of reading,” says Sterne, as he demonstrates in this wonderfully rambly novel that spends several volumes narrating the events of its hero’s birth. Uncle Toby, forever fixated on recreating the Siege of Namur in miniature, is one of literature’s great comic buffoons.

81. London Labour & the Labouring Poor, by Henry Mayhew

A 3,000-page work of investigative reporting, in four volumes, on the living conditions of London’s poorest in the 1840s and ‘50s. We meet a steamboat concertina player, a man who peddles beer on the river, a seller of snails and birds’ nests, a penny mousetrap-maker, the original “silly billy” (a singer of comic songs). It is so fun and so sad.

80. Les Miserables, by Victor Hugo

We need to bring back the encyclopedic novel. We need more books in which the author embarks on poetic, fifty-page digressions about the sewers of Paris and the argot of street urchins. We need more books in which the hero, after leaving prison, buries 600,000 francs in the woods and leaves them there.

79. The Pilgrim’s Progress, by John Bunyan

Despite its reputation as something of a chore, I think this book is fun even if you don’t subscribe to Bunyan’s theology. There’s a wry undercurrent of comedy running through it: you can’t read the episode involving Pliable and Obstinate without laughing. (Skip the second book, in which the pilgrim’s wife and children tour the sites from the first book.)

78. The Essex Serpent, by Sarah Perry

Perry is our reigning master of the Gothic, a writer—raised on Thomas Hardy and the King James Bible—who refashions Stoker, Collins and Drood-era Dickens into something new and strange. Here, via the story of a lake that may or may not harbor a prehistoric serpent, she explores the tensions between faith and reason in the age of Darwin.

77. Catch-22, by Joseph Heller

Yossarian is the only sane person in the 256th Squadron. He tries to escape combat by pleading insanity, but in doing so proves he’s sane and must fly more missions. It was Heller’s fate to write both the funniest and saddest of modern novels (“Where are the Snowdens of yesteryear?” indeed). I named my sister’s dog “Major Major Major Major.”

76. The Kalevala, by Elias Lönnrot

This lengthy Finnish poem, featuring magic swans, monstrous fish, a shaman who creates with the power of song, and a truly shocking amount of beer-brewing, numbered among Tolkien’s chief influences. It’s possible to enjoy the book purely for its rhythmic beauty and the author’s delight in the natural world: in rain and frost, in vast oaks, in russet-hued mountains and salmon-teeming grottoes.

75. The Diary of Samuel Pepys (edited by Robert Latham)

One of the great London books, but also an unflinching self-portrait of a man of big appetites (for music, for money, for women), whose virtues—his honesty, his curiosity, his Chaucerian delight in the world, and in living—somehow balance out his excesses. Read Claire Tomalin’s Pepys: The Unequalled Self for a good intro to Pepys and his world.

74. Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver

Dickens by way of Friday Night Lights. An orphaned boy finds glory on the football field as poverty, drug addiction and the contempt of the more fortunate conspire to destroy the lives of his loved ones. As I wrote in my review for Bas Bleu, Kingsolver scrubs the dust from Dickens like a Renaissance statue that was in need of a light polishing.

73. Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott

Drawing inspiration from Bunyan and Dickens, Alcott’s coming-of-age epic derives much of its power from the gradual changes in the lives of its sharply drawn heroines, with the seasons used as ritual markers in a manner that would later influence Harry Potter.

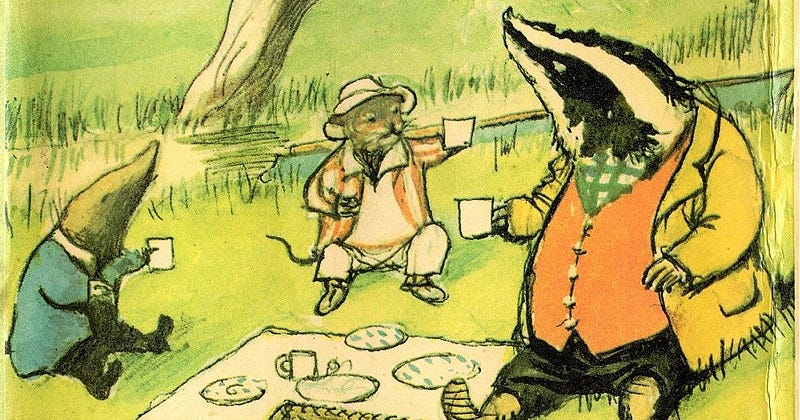

72. The Wind in the Willows, by Kenneth Grahame

The prototype of all children’s books about talking animals features much messing about in boats and the memorably chaotic adventures of Toad of Toad Hall, who cries “Poop-poop!” as he zips past in his new motor-car. This was the book that converted Terry Pratchett into a book-lover at the age of six.

71. Bradbury Stories and The Stories of Ray Bradbury

Two collections, each containing 100 short stories. In “The Scythe,” a man finds himself the master of death. In “A Sound of Thunder,” a time-traveler steps on a prehistoric bug to disastrous effect. In “There Will Come Soft Rains,” robotic servants continue to perform their functions long after a house’s human occupants have been killed.

70. Northanger Abbey, by Jane Austen

Catherine Morland, a young woman whose head has been turned by reading too many Gothic novels, begins to suspect that she might be living in one when General Tilney invites her to stay at Northanger Abbey. Jane’s funniest, and strangest, book.

69. Endless Night, by Agatha Christie

Michael Rogers falls in love with a beautiful but naive heiress named Ellie, and together they build a house on a cursed plot of land. One of Christie’s darkest and most disturbing novels, a psychological thriller that draws inspiration from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

68. Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years [Extended Edition], by Mark Lewisohn

The first in a projected three-volume biography of the Beatles, from their childhoods in Liverpool to Abbey Road. This book, the only one yet published, ends with “Love Me Do” but still clocks in at 1,700 pages. The chapter describing John and Paul’s first meeting at a church function in 1957 is a small masterpiece of narrative nonfiction.

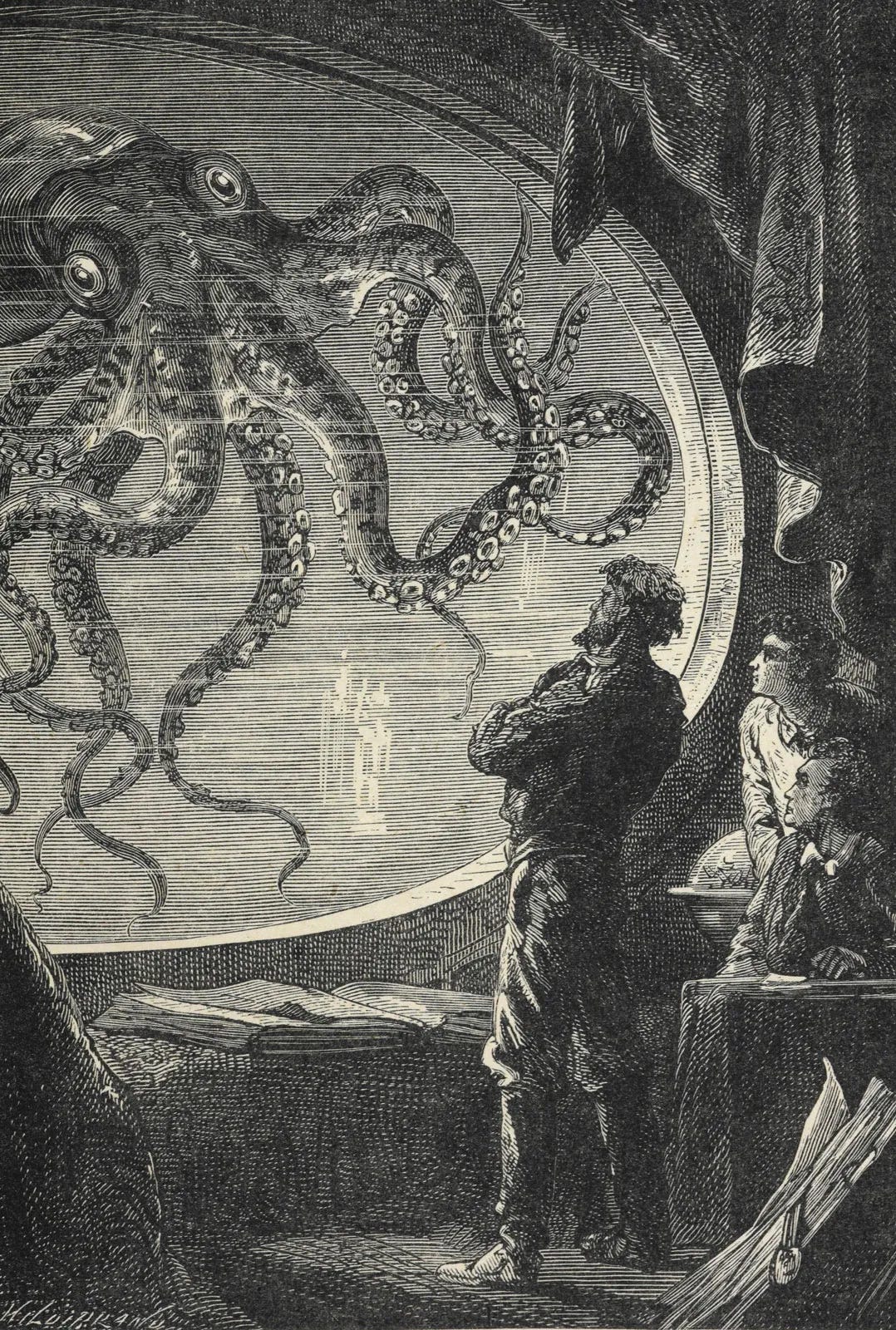

67. A Journey to the Center of the Earth, by Jules Verne

While it lacks the Gothic melodrama of Twenty Thousand Leagues, there’s something wonderfully pulpy about this story of a message found in an old book that leads Axel and his uncle Otto Lidenbrock down an extinct volcano, through a warren of tunnels and caverns, where they discover a fully preserved prehistoric world.

66. The Princess and the Goblin, by George MacDonald

MacDonald’s most inventive children’s book centers on the conflict between a girl named Irene and a race of underground goblins who have sensitive feet. The slaughter of the goblins in the book’s denouement is cleverly orchestrated but disquieting. MacDonald drew upon his memories of working in a castle library for the setting of this book.

65. The Magic Apple Tree: A Country Year, by Susan Hill

Don’t let the title mislead you: this is a thoroughly realistic memoir of a year spent baking and gardening in rural Oxfordshire. Owls perch, fog rises from the fens and fox-cubs shriek with hunger on cold nights. Hill ably captures the magic of the vanishing landscape that has inspired so many of England’s best fantasies.

64. The Westing Game, by Ellen Raskin

Deserves a place alongside Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on the list of perfect premises: sixteen heirs are invited to attend the reading of the will of Samuel Westing, where they’re given a series of clues and told that the winner of the titular game will inherit his entire $200,000,000-dollar fortune. It all builds to a really lovely denouement.

63. The Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer

The best way to read this poem is in the original Middle English—it’s close enough to modern English that one can manage well enough with an annotated edition. Chaucer’s style is uniquely untranslatable, his joy so capacious, his wit so shrewd and keen.

62. Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, by Pu Songling

A collection of weird tales (running to twelve volumes in the unabridged translation) featuring disguised ghouls, ghostly monks, boar spirits, magic pear trees, and a clever fox who patiently plots vengeance on a genocidal neighbor who wiped out his entire clan.

61. The Wizard of Oz series, by L. Frank Baum

The first book is, arguably, the most successful attempt by anyone to write an American fairy-tale. But there’s much fun to be had in the series’ thirteen other books, including the Highly-Magnified Woggle-Bug, a princess with a detachable head, and an ill-advised quest by the Tin Woodman to find the woman he loved before he was made of tin.

60. Flavia de Luce series, by Alan Bradley

A series of eleven books (and counting) about a precocious tween living in an English village in the early 1950s. Flavia has two older siblings (whom she finds deeply annoying) and a frankly unnerving knowledge of chemistry, which she uses to solve crimes. The real glory of the series is her narrative voice, equal parts brash, put-upon and endearing.

59. Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Brontë

“There was no possibility of taking a walk that day.” One could argue that this novel contains the single best twist in all literature. But even sans twist it’s a terrific read, richly atmospheric, keenly attuned to the experience of being young, and a woman.

58. The Phoenix and the Carpet, by Edith Nesbit

This second book in a series about five English siblings begins with the discovery of an egg inside an old carpet. The carpet is a flying carpet and from the egg emerges a phoenix: a vain, pompous, lovable phoenix who leads the children on adventures in London and the French countryside, leaving good-natured chaos in his wake. Excellent fun.

57. Nevermoor, by Jessica Townsend

My favorite middle-grade series of the past decade, a whimsical blend of Doctor Who, Lewis Carroll and Little Women that also has important things to say about immigration, scapegoating and belonging. It’s the imaginative touches—like Fenestra the Magnificat and the ever-shifting Hotel Deucalion—that make the book endlessly re-readable.

56. Charmed Life, by Diana Wynne Jones

The Chrestomanci books, centering on a powerful magical bureaucrat named Christopher Chant, glean much comedy from the tension between the books’ understated narration and the anarchic premise. The spells performed by the wicked young Gwendolen are recounted in the sort of tone one typically associates with a weather report: her brother, playing the violin, “found, to his dismay, that he was holding a large striped cat by the tail.” The cat runs away, “and that was the end of the violin lessons.”

55. The Picture of Dorian Gray, by Oscar Wilde

Dorian Gray makes a Faustian bargain—he will remain forever young while his portrait grows older and more wicked. Decadent and surreal, steeped in the baroque excess of the Arabian Nights, Wilde’s only novel has the air of a slowly unfolding nightmare.

54. Five Little Pigs, by Agatha Christie

Poirot is drawn into a cold case involving a woman who was imprisoned sixteen years ago for a crime her daughter is certain she didn’t commit. Thematically rich and devastating in its resolution, this is the most emotionally moving of all Christie’s novels.

53. Piranesi, by Susanna Clarke

Another fantasy masterpiece by our greatest living author, about a man living alone in an endless house with an ocean on its lower floor. The only other occupant is a man known as The Other who meets with him twice a week. Clarke mixes Borges, The Magician’s Nephew and the “Heaven Sent” episode of Doctor Who to thrilling effect.

52. Special Topics in Calamity Physics, by Marisha Pessl

An early entry in the “dark academic” subgenre whose real selling point is the eccentric voice of its teen narrator, Blue Van Meer, who leads a nomadic existence with her brainy but embarrassing father. Reads at times like a deranged spoof of The Secret History; the fake book titles and left-field descriptions (“a skin-and-bones greyhound with the red eyes of a middle-aged, midnight tollbooth collector”) are a highlight.

51. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell

It’s tempting to wonder what Mitchell might have written had she not died tragically young. Her lone novel is powered by one of American literature’s great casts: rakish Rhett Butler, vacillating Ashley Wilkes, and above all Scarlett O’Hara, whose loose ethics, fierce temper and impulsive habits inspired the character of Jaime Lannister.

50. Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, by Jules Verne

The Nautilus drawing room, with its rococo design and massive window gazing out on the wonders of the deep, is one of literature’s great settings—a precursor of the TARDIS. Captain Nemo’s despair over the loss of his family and rage at the unnamed colonial power fueling his quest for revenge elevates the book into something almost mythic.

49. Dr. Gideon Fell series, by John Dickson Carr

Carr was an American anglophile with a Doyle-esque flair for the dramatic, and the twenty-four Gideon Fell novels—featuring a pipe-smoking detective modeled on G. K. Chesterton—are wonderfully weird, with their witches, robots, vampiric flying women and murders via green capsule. A bit like Agatha Christie on acid. (Christie was a fan.)

48. The Hound of the Baskervilles, by Arthur Conan Doyle

One of those rare books that seems to embody a whole era: when we think today of the late-Victorian period in which the book is set, instantly we picture Watson and Holmes bestriding marshy Dartmoor, pistol at the ready, in pursuit of the titular beast.

47. Don Quixote, by Miguel Cervantes

“What if a man read so many stories he began to think he was the hero of one?” is an all-time great premise, and with it Cervantes almost single-handedly launched the modern era. It’s been said that the germ of every subsequent novel is found in this one.

46. Watership Down, by Richard Adams

Unfairly dismissed as a children’s story, Adams’ unlikely epic about the journey of a rabbit colony to a new home following a prophecy of their warren’s destruction borrows its structure from the Aeneid and its episodes from earlier fiction and folklore, in the process creating a new mythology that approaches, and at moments rivals, Tolkien’s.

45. Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison

Our unnamed protagonist (“invisible” because he feels unseen) recounts in flashback his expulsion from college, a stint in a New York City mental hospital, and meetings with racists, cultists and assorted oddballs, in a poetic language that channels Melville and anticipates the music of Bob Dylan. “All dreamers and sleepwalkers must pay the price.”

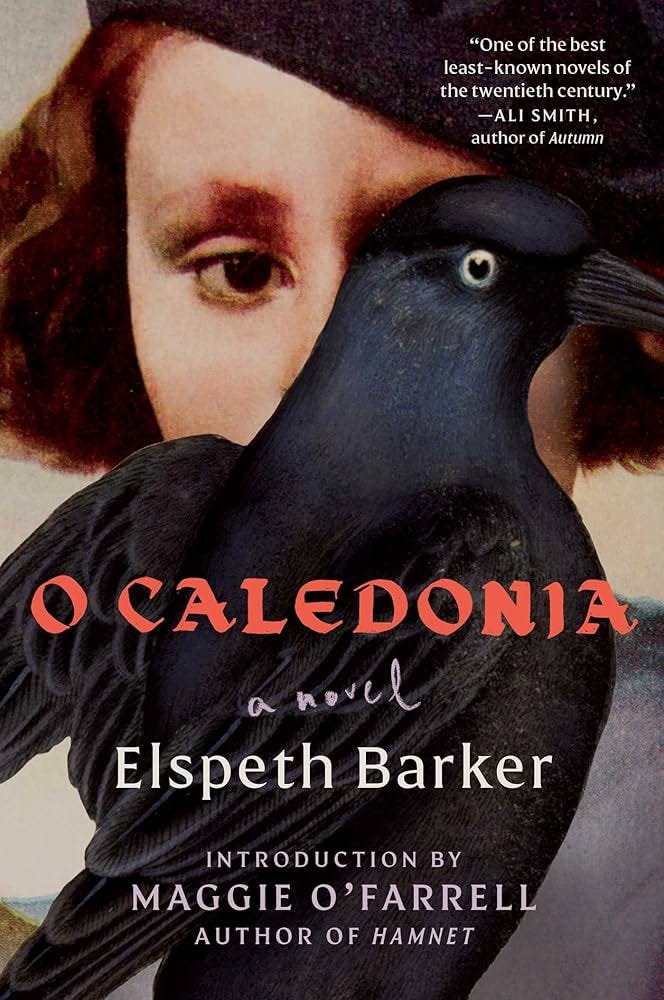

44. O Caledonia, by Elspeth Barker

Barker only wrote one novel, but oh, what a novel. This slender tale of a sixteen-year-old girl who would rather be reading Gothic fiction and traipsing about the Scottish Highlands with her pet raven than attending boarding school is very nearly perfect.

43. As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams, by Lady Sarashina

An eleventh-century memoir written by a Japanese lady-in-waiting, recounting her travels across the island, the dreams she had on the way and the sudden death of a beloved sister. Dream and reality mingle until it’s hard to say which is which.

42. Hogfather, by Terry Pratchett

My favorite Discworld novels tend to be the ones featuring Death as a main character, and in this—one of the best books he ever wrote—Death must impersonate the Discworld version of Santa after he’s abducted on Hogswatchnight. Mayhem and hilarity ensue.

41. A Song of Ice and Fire, by George R. R. Martin

Forget the TV series. The plotting of Martin’s series is astonishing in its intricacy, with small decisions in one book reverberating tragically hundreds of chapters later. Few people are capable of writing with this level of complexity; as the story has grown, even Martin seems overmatched by it, as his ongoing attempts to finish book six have shown.

40. War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy

The reputation of Tolstoy’s magnum opus is unfairly dogged by its length—some 1,200 pages—but this story of young people in Russia on the cusp of war with Napoleon is terrifically breezy, with its unrequited loves, attempted assassinations and drunken boys foolishly tying a policeman to a bear and throwing the bear into the Moyka Canal.

39. The Faerie Queene, by Edmund Spenser

A really delightful poem in six volumes that speaks of questing knights, cunning dames, evil twins, enchanted isles and a prince who literally hurls himself over a castle’s walls, Richard the Lionheart-style. Once you get into the rhythms of Spenser’s verse, it’s hard to let go.

38. The Complete Anglo-Saxon Poems (Williamson translation)

Of course Beowulf was going to appear on this list—a fist-pumping Old English epic of mead halls, treasure hoards and late-night battles with hell’s fiends—but don’t sleep on the other poems from that era, including “The Wanderer,” a lament for winter, broken friendships and the ruin of the world.

37. The Penguin Book of Norse Myths, by Kevin Crossley-Holland

For my money the single best retelling of the Norse myths, preserving the dense worldbuilding of the old tales while adding considerable narrative flair. Without altering or dumbing down the stories (ahem, Gaiman), Crossley-Holland makes them irresistibly enjoyable.

36. I Capture the Castle, by Dodie Smith

“I must admit that our home is an unreasonable place to live in. But I love it.” Cassandra Mortmain lives in a house grafted onto a castle, to which her father retreated after being wrongly imprisoned for attempted murder. Cassandra recounts her flirtations, frustrations and various schemes to save her father from despair in this irresistibly charming book.

35. Icelandic Sagas

“The prose literature of medieval Iceland is a great world treasure,” says Jane Smiley, “elaborate, various, strange, profound.” In the forty-one surviving sagas, corpses come alive, warriors become slam-poets, beautiful women provoke generational feuds and old friends commit sudden, shocking acts of violence.

34. The Dream of the Red Chamber / Story of the Stone (book one), by Cao Xueqin

Come for the curses, enchanted mirrors, and poisoned soups; stay for the richly layered saga of romantic rivalry and aristocratic decline, in this beloved Chinese novel that has drawn comparisons with Marcel Proust.

33. Dickens, by Peter Ackroyd

One of the rare biographies that almost reads like a lost novel by the author it portrays. Ackroyd elevates the genre with obsessive levels of detail that render the book a kind of mosaic presenting the totality of a man’s life. There are uncanny flashes of insight such as one seldom gets in books of this sort: one creative genius contemplating another.

32. The Odyssey, by Homer

There are few more exciting passages in literature than the middle stretch of this poem featuring the Lotus-Eaters, Circe and the Cyclops, but then Homer takes a hard swerve into realism with one of the most unsettling depictions of post-traumatic stress and mass slaughter ever written.

31. The Magicians, by Lev Grossman

Quinten Coldwater, a jaded teenager with a hopeless crush on his oboe-playing best friend, finds himself admitted to a secret college for magicians. But getting everything you ever wanted has its price, as he soon learns in this ferociously funny and savage deconstruction of Narnia, Harry Potter, and the adults who still stubbornly love them.

30. The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexander Dumas

When Edmond Dantes escapes prison, he acquires a fortune and plots revenge on the former friends who conspired to put him away. Quite simply the greatest adventure novel ever written, a book that wields wish-fulfillment like a weapon and leaves you cheering for Dantes’ every deranged scheme.

29. Brideshead Revisited, by Evelyn Waugh

One of the twentieth century’s great novels. Charles Ryder’s Oxford is the best portrayal of the city in print, and the story of his fraught relationships with the Flyte siblings over several decades, from early ecstasies to ultimate dissolution, is unbearably moving.

28. Cat among the Pigeons, by Agatha Christie

Our favorite Belgian sleuth must find the link between the death of a crown prince, some missing rubies, and a series of murders at a girls’ boarding school. He’s assisted by a spirited young student named Jennifer in Poirot’s most delightful and exciting adventure.

27. Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury

Perhaps the most prescient of the great dystopian novels, an increasingly unnerving vision of a world in which screens command all attention, the police engage robotic killer dogs in ruthless pursuits and most people have forgotten how to read, or think.

26. His Dark Materials, by Philip Pullman

Few children’s authors would possess the ambition to attempt a retelling of Paradise Lost with flying witches, armored polar bears and an alternate-world version of Oxford. Fewer still would be able to pull it off. Christians who criticized the series missed the point. Yes, Pullman is an atheist, but an Anglican one.

25. The Midnight Folk and The Box of Delights, by John Masefield

Witches, foxes, pirates, a cat named Nibbins, an evil governess, a dodgy vicar, a useless policeman, excursions into the past to meet King Arthur and the Romans… For anyone who ever yearned for more Narnia books, Masefield’s children’s books are unrivaled.

24. The Magician’s Nephew and The Silver Chair, by C. S. Lewis

The deeper you go into the Narnia books, the weirder they get. The Magician’s Nephew features some terrific set pieces—the Wood between Worlds, Charn, Jadis in London—while The Silver Chair gives us an underworld voyage and, in Puddleglum, one of the series’ best characters.

23. Bleak House, by Charles Dickens

Not my favorite Dickens novel, but possibly his best. London is the central character, a London of legal wranglings and starved newborns, of blinding fog and ancient pensioners “wheezing by the firesides of their wards.” His flair for atmosphere, his facility for language, reaches its apotheosis in this book. Line for line, a work of unfettered genius.

22. Mammoth Book of Celtic Myths & Legends, by Peter Berresford Ellis

Outside of the Arabian Nights, probably my favorite collection of folktales. A cat and a roach form a band, the greatest of Irish warriors is seduced by an undersea goddess, and a young woman working for a mysterious lord is obliged to place an ointment over her eyes each night before bed.

21. Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories, by Agatha Christie

There’s something bracingly soothing about these early stories, with their Art Deco-saturated interwar setting and the easy camaraderie between Poirot, Arthur Hastings and the dogged police inspector Japp. Highlights include “The Cornish Mystery” and the novella “Dead Man’s Mirror.”

20. The Man Who Was Thursday, by G. K. Chesterton

The book Susanna Clarke says she wishes she’d written. A satire, a spy thriller, a poem, a riddle, an existential fable… there’s no other book quite like it. Chesterton paints London with all the vividness of a hallucination, and the ending makes me cry every time.

19. The Mahabharata (Ramesh Menon translation)

A two-million-word poem centering on the war between five brothers and their hundred wicked cousins—and featuring serpent kings, trickster gods, prophecies, curses, betrayals and a woman who is reborn as a man to get revenge on an ex-lover.

18. An Encyclopedia of Fairies, by Katharine Briggs

The best book ever written on traditional faerie lore: several hundred stories of mysterious beings who can change size, cast spells of illusion and make crafty bargains. Susanna Clarke’s primary reference for the lore in Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell.

17. Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens

Katie Lumsden said recently on YouTube that she didn’t love this book until she had grown up and made some embarrassing mistakes. There are some terrifically strange moments—Magwitch in the graveyard, Miss Havisham’s wedding cake—but what the book does best is to capture that feeling of being young and confident and clueless.

16. Ulysses, by James Joyce

Ignore the folks who insist this book is a confusing slog. It’s not only accessible but also immense fun. There’s one layer in which Joyce is painstakingly recreating a single day in Dublin. There’s another in which he’s having a romp with myth and language: “The Oxen of the Sun” chapter, which parodies a number of English authors, took a year to write.

15. Collected Fictions, by Jorge Luis Borges

Borges, who never wrote a novel, is the undisputed master of contemporary weird fiction. In “The Library of Babel,” people are born into a near-infinite library whose books contain every combination of letters. In “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a man must murder a beloved scholar who’s uncovered the secret of the strangest book ever written.

14. The Gormenghast Trilogy, by Mervyn Peake

This tale of an eccentric family living in a vast, crumbling house is elevated by its attention to the absurd minutiae of ritual and its feverishly poetic language. The clever but dastardly Steerpike is one of the great anti-heroes in literature.

13. The Hebrew Bible: The Wisdom Books and Prophets

Like the complete Shakespeare, the Bible defies ranking. Trying to slot it on a list like this would be a fool’s errand; but my favorite bits include the Book of Job, Ecclesiastes, Isaiah, Jeremiah and the twelve Minor Prophets, books that have shaped my literary and ethical sensibilities like nothing else. (Preferred translations: the King James, Knox, Alter.)

12. Late Plays of William Shakespeare (Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, The Tempest)

Shakespeare achieved a poetic brilliance in his late plays that no one has ever approached, let alone equaled. His language grew ever more baroque, his stories increasingly surreal, culminating in the dream-like perfection of The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest. In his tragedies, meanwhile, the all-seeing Bard of Avon grappled with the deepest riddles of life and death in an absurd world.

11. Sir Gawain & the Green Knight

The most fun you can have in the fourteenth century, this poem about a knight who must travel across country to face his own death at the hands of a green man is full of rain, horror and jollity. If your Middle English is a bit rusty, try the Tolkien translation.

10. Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

It’s possible to enjoy this as a straightforward story about the hunt for a murderous whale, but half the fun lies in Melville’s bizarre, postmodern digressions on time, eternity, marriage, madness, and buckets of sperm. If there’s a Great American Novel, it’s this.

09. Harry Potter (books three through six), by J. K. Rowling

I read these books at age nineteen after years of reading Nesbit, Lewis and Lewis Carroll, and could see right away that Harry Potter was the heir to that storytelling tradition. Few other series blend folklore, mystery, medievalism and teen drama to such engaging effect. By the time I finished Order of the Phoenix, I knew I had to become a mystery novelist.

08. The Lord of the Rings, by J. R. R. Tolkien

Of the three books, I slightly prefer the first one. The flight from Bag End to Rivendell, with its hairbreadth escapes and strange interludes, is perfect reading for a cold night—and was heavily influenced by Pickwick Papers.

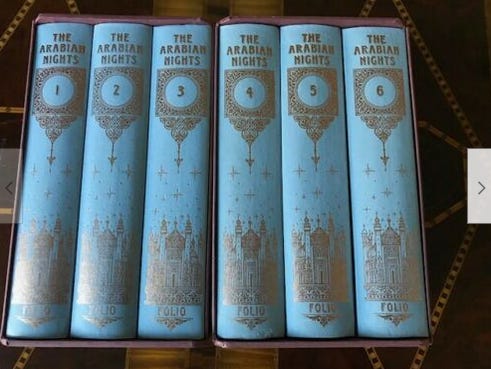

07. The Thousand and One Nights (Mathers translation)

I rave about this book exceedingly because it’s so wonderful. It was beloved by Charles Dickens and H. P. Lovecraft. It includes early whodunits and science-fiction. It’s like a Twilight Zone for the middle ages, extravagant in its weirdness, generous in its pleasures.

06. Swann’s Way and In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, by Marcel Proust

I’m rapidly reading the seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time; it may climb still higher as I finish the later books. Don’t let the book’s reputation scare you—Proust is gorgeous, funny and accessible, and no one has ever written more astutely about human behavior.

05. Le Morte d’Arthur, by Thomas Malory

The single best collection of King Arthur stories. Malory’s prose is still delightfully readable six hundred years on, and he understands that Camelot is supposed to be a weird place where weird things happen for no discernible reason.

04. The Pickwick Papers, by Charles Dickens

It’s slightly infuriating that Dickens wrote this at the age of 24, because it is possibly the best novel by a debut author. This is the ultimate comfort read, a book of episodic adventures amid stableyards and pubs and warm inns on winter nights.

03. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, by Susanna Clarke

The best book of the century so far, a story of two magicians who are first friends, and then rivals, and how one of them inadvertently “opens a door to hell and lets the devil into England.” Beautiful, eerie, superb.

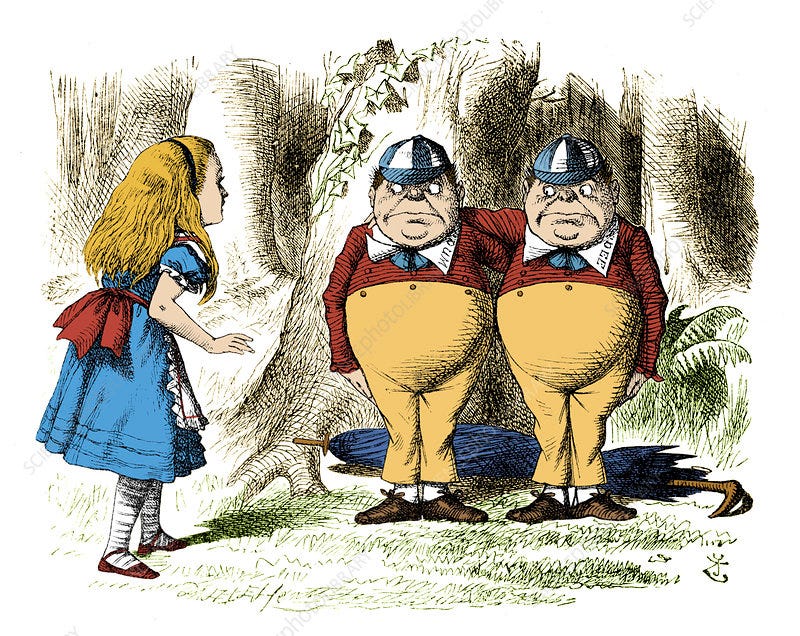

02. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, by Lewis Carroll

You should read both of the Alice books, but I slightly prefer the second. It’s funnier, weirder, and sadder, and had a massive effect on the Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper’s era. Alice’s journey through a funhouse version of Oxford improves as one ages, acquiring new layers of cleverness and pathos. Carroll had Homer’s gift for creating visually iconic characters: the Cheshire Cat, the Tweedle Brothers, the goat on the train wearing a newspaper hat, burrow into one’s brain and never leave.

01. David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens

It’s conceivable that someday another book could displace David’s hold on my affections, but in thirty years of searching I have yet to find its equal. This is Dickens at his absolute peak: the plotting perfect, the characters (Uriah, Steerforth, Rosa Dartle) instantly memorable, the losses and betrayals never more devastating. Dickens considered it the best of all his books; and there’s probably no other book of his in which comedy and heartache are so keenly balanced. Like the Bayeux Tapestry or “Eleanor Rigby,” this book is a treasure of human culture. We are very lucky to have it.

This is a perfect list, not because it is one that I (or anyone else) would have compiled, but because it consists of your beloved lifelong literary companions. So much more valuable (and fun to read!) than a concoction, from some pseudo-omniscient perspective, of "greatest" books.

This seems like a portrait of the writer as a young man--you, Boze. What has shaped your sensibilities and corresponded with them.

It reminds me that the world of books is so very vast. And, it is critical that we read what appeals to us and (to echo theologian Howard Thurman) "brings us most alive."."

I learned alot reading your list and the thumbnail sketches--e.g., "one can’t help wishing Milton had gone with his initial plan to write an epic about King Arthur" in the context of "Paradise Lost."

You awakened my desire to re-encounter some great works--e.g., "Chaucer’s style is uniquely untranslatable, his joy so capacious, his wit so shrewd and keen."

You made me appreciate a possibility--that a literary critic and biographer, Peter Ackroyd, could be a genius in his own right: "one creative genius contemplating another."

Keep promoting the incalculable benefits of reading.

“Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” – Frederick Douglass