A Child Composed of Books

How Reading Became Endangered ... and How We Can Save It

Author’s note: Friends, welcome to our substack. For my first post I’m sharing here the preface to a nonfiction book I’m currently writing on the importance and joys of reading - an especially salient issue at a cultural moment when literacy and the humanities in all forms seem to be under attack.

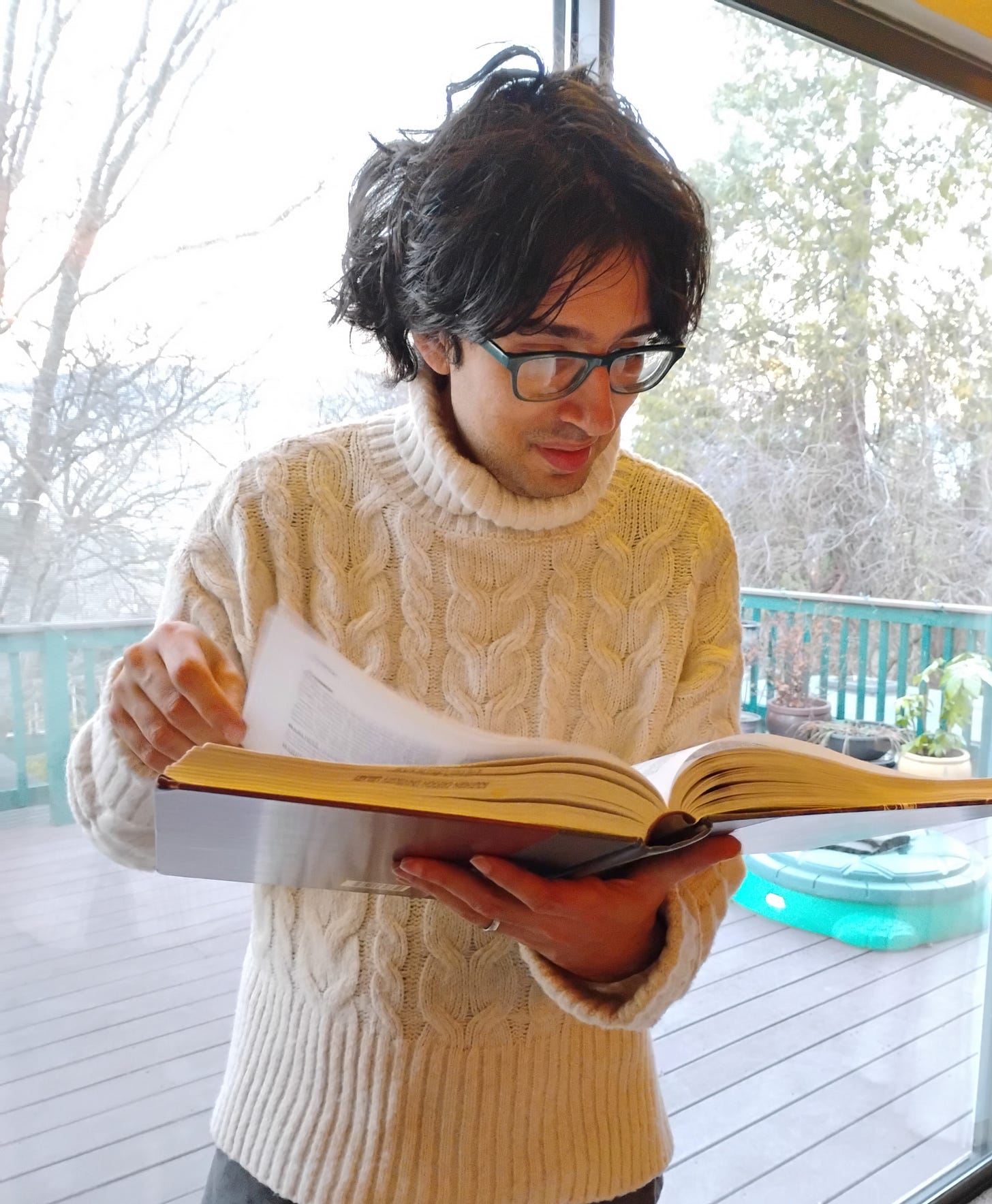

For as long as I can remember, I have been in love with reading.

Which is another way of saying: growing up I desperately needed an escape. And I found it in books.

I was a scrawny, mop-haired child who knew a great deal about all the wrong things. I could list all the muscles in the arm but struggled with tying shoes. I didn’t know that walking up to another child and reciting a hundred-year-old poem from memory is more unnerving than impressive. (I support the memorizing of old poems, but there is a time and place.) I once spent an entire evening making a necklace out of dried macaroni pasta for a girl at school on the occasion of her fourteenth birthday, and was puzzled when she never wore it in public (or, I assume, ever).

“Boze, you’re so smart,” Mrs. Brumbelow, a teacher, informed me. “But sometimes you can be so damn dumb!”

I had few friends. And at the time, my family’s financial situation wasn’t spectacular. We lived in a rented mobile home in a corner of Texas that baked in the summers and flooded during the rainy season. We battled roach and fire ant infestations. My trousers (I insisted on calling them “trousers,” because even then I wanted to live in England rather than Houston) never seemed to fit, and my socks had an odd smell. Poverty is a hard thing. We’ve been led to believe it’s the fault of the parents (for not working hard enough) or even the fault of the child (for choosing to be born into the wrong family), when often the blame lies with policies that are inscrutable and opaque, if not willfully harmful.

I didn’t know all this at the time. I only knew I was different, that other kids lived in nice homes, that no one wanted to sit next to me during history class. But I wouldn’t have described myself as poor.

We had enough. We had books.

Every few weeks, Mom drove me down to the local paperback exchange and allowed me to pick out one book. We raided library and yard sales, received book parcels from kindly strangers who were downscaling their collections, were gifted volumes of Jules Verne and Mark Twain by neighbors who sensed my burgeoning reading obsession. As a result of which, I sometimes have an impression of 1990s America as being awash in cheap books. Certainly it was a more literate culture. Wishbone, a kids’ TV series about a dog who pretends to be Darcy, Faust, and various other characters from classic literature, was a mainstay of PBS afterschool programming. Walmart, if you can believe it, sold cheap editions of the classics with garish covers, two for a dollar. On Sunday nights, network television featured miniseries adaptations of Gulliver’s Travels (starring Ted Danson) and Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. The “baddies” in movies quoted William Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde, lending even the most mindless action thriller a veneer of sophistication. And in 1995, Colin Firth emerged wet-shirted from a lake and launched a Jane Austen revolution.

The message I imbibed from the culture was this: classic books are fun and exciting. Classic books have the power to change your life. You need to be reading the classics.

So in the fifth grade I began reading the classics, and the course of my life was set.

The first book I ever fell in love with—real love, the kind that keeps you reading into the night hours; nerve-shattering, bone-deep love—was Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. After the Bible, it is the book that has shaped me more than probably any other. As a child I was charmed by the strangeness of it, and the violence lurking just barely glimpsed beneath the surface—the fact that Alice is gainsaid and bossed around by nearly everyone she meets—was reassuring. Carroll understood me. When older folk said I needed to go outside and play rather than reading Alice (or its superior sequel, Through the Looking Glass) for the twenty-third time, I felt I had found in him a secret ally. For a long time, the Cheshire Cat was my only friend.

But soon there were others. The March sisters and Laurie from Little Women. The unnamed second Mrs. de Winter from Rebecca. Atticus Finch and Meg Murray and Anne Frank, who, with her unrealized dreams of being a journalist, planted the seeds of my own literary ambitions. Laura Ingalls. The Time Traveller. Pierre and Natasha, in a lightly abridged edition of War and Peace. The foolhardy trio that ventures down an Icelandic volcano into a prehistoric world of giant mushrooms and quarreling sea monsters in one of Verne’s novels. And then in the autumn of my tenth year, like the flash of lightning that precedes a shower of rain, a book by Charles Dickens entitled David Copperfield.

Reading David was the sort of experience you have only once or twice in your life. The basic story—about an orphaned boy who absconds from the blacking factory where he’s been employed by his abusive stepfather and journeys on foot from London to Dover (a distance of about eighty miles) seeking the care of a stern aunt who abandoned him as a newborn—has proven enormously influential. The plot is one that Dickens had been tinkering with for years—his second novel, Oliver Twist, is an early version—but here he brings it to a kind of perfection, a shining apotheosis, that would serve as a template for the next 160 years of popular storytelling. Stephen King drew inspiration from it. Barbara Kingsolver modernized it, to great effect, in her Appalachia-set novel Demon Copperhead. You can see the bones of the story peeking through the skin of the Harry Potter books, which is part of the reason for their astonishing popularity.

Good storytellers figure out how to adapt the emotional substructures of this and his other books for their own works, because Dickens knew, better than nearly anyone in history, how to arrange a plot in such a way that your ribcage vibrates with sympathy for the hero and deep moral outrage at the schemes of the villains. He was, I would argue, the James Cameron of his day: a beloved entertainer with an instinctive grasp of the feelings of a mass audience and how they could be most effectively galvanized. And he never missed. In the words of Sam Anderson, Dickens “plays the entire xylophone of a reader’s value system, from high to low; you can almost feel the oxytocin dumping, sentence by sentence, in your brain.”[i]

And when you’re ten years old, feeling lonely and neglected and uncertain of your place in the world, the effect is like a narcotic.

It baffles me when people use Dickens as their example of an “old, boring writer,” because I had never encountered anything as propulsively readable as David Copperfield. I read it in my desk after completing assignments, in the back of the car as we drove through Galveston’s historic district, the salt spray on my face evoking the novel’s coastal setting. No matter that I couldn’t parse every plotline, that I found myself, on a few occasions, lost in a thicket of Dickensian verbiage. My love of the characters—the longsuffering Agnes; the odious Uriah Heep, oozing false modesty and writhing in an eel-like fashion; the rakishly handsome, doomed Steerforth—kept me reading through the more difficult bits. Then, towards the end, there came a scene of such devastating power (anyone who has read the book will know) that I’ve never seen its equal. It exploded my understanding of what’s possible on the printed page, of the emotions a story well-told is capable of summoning. After closing the book for the first time, I was resolved: I would either succeed in becoming a writer, like David, or fail bravely in the attempt.

* * *

Seven years later, I applied for admission to Southwestern University, a small, private liberal arts college near Austin, in the heart of the Texas Hill Country. Somewhat to my surprise, I was accepted. I spent the first few days walking alone across campus, in the shade of the vast live oaks, in a sort of happy dream. It seemed too wonderful to be real, and that was before I even set foot in the library.

I planned my first visit for a weekday morning when I had nothing else scheduled. Entering through a cool foyer, I stepped into the main room, gazed round—and my heart sank in disappointment.

There were only about four shelves total, each stocked with niche reference books, dictionaries and encyclopedias (none of which were available for checkout). A display of new releases was more promising, but buzzy literary fiction and insider accounts of the Bush White House weren’t enough to sustain me over the next four years. I needed real intellectual nourishment. As I wandered amid the stacks, my sense of despair became acute. What sort of school was this? Had I made a mistake in not visiting the campus before I applied?

When I could bear it no longer, I strode to the front desk. There a girl just a few years older than me was seated arranging books on a rolling cart.

“Sorry to bother you,” I said in a vaguely accusing tone, “but I was wondering: where are all the books?”

She studied me knowingly for a moment. Then, with an air of barely restrained sarcasm, she motioned to the stairwell at the far end of the room. “Why don’t you try going up the stairs…?”

I took off like a shot.

After that morning, I never again—or at least not for a long time—harbored second thoughts about having enrolled at SU. The school library was vast, much vaster than I had imagined: some 300,000 volumes housed in a building of three stories. There were odd nooks where one could hide for hours without fear of encountering another person; shelves on rails that rolled from left to right, or right to left, at the turn of a wheel, which yielded some rather graphic folklore about murders committed in the stacks; alcoves with squashy armchairs that nearly swallowed me whole when I sank into them (and in which I enjoyed some of the best naps of my life).

Each day when class let out, I headed for the library, spent a few minutes browsing at random until I found a book on a subject that pleased me—glaciers, interstellar space, Buddhist conceptions of heaven and hell, the spiritual meaning of alchemical symbolism—and read until dinner, at the end of which I would return and read through the evening. On Saturdays I sometimes spent the whole day reading. It was here that I discovered what are, to this day, some of my favorite books: The Man Who Was Thursday, a surreal spy thriller that’s one part comedy, one part nightmare, and ends with a sequence that always leaves me in tears; the Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights, a seemingly endless collection of medieval Middle Eastern folktales about which I became (and remain) extremely annoying; and Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers, which I brought home one Christmas and stayed up until daybreak reading on three successive nights. (There never was a more comforting book.)

Being there was bliss, to the point where, when I left and moved away, I felt bereft. The years after graduation were prodigal with grief—I lost a best friend, a bookish kindred spirit with whom I had been quietly in love, in horrific fashion, and for a number of years the ache of her death eclipsed all lesser travails. “Where the greater malady is fix’d,” says King Lear, “the lesser is scarce felt.”[ii] But I still felt the library’s absence keenly. How did people manage, I wondered, who didn’t live near a large metropolitan or university library? How did they satisfy their hunger to learn everything, to read everything?

But as it happened, I was asking the wrong questions. For in the years after I graduated from Southwestern in 2008, a terrible thing was beginning to happen. Fewer and fewer people were reading, for knowledge or pleasure. Fewer people were reading at all.

I noticed the change in myself first. Shortly after Bethany’s death I acquired my first smartphone. In the year or two that followed I found myself reading less and less. The number of books I read in a year declined steeply. My ability to focus on texts for extended periods evaporated. The internet was a carnival of distractions and there was always some shiny but insubstantial trinket to draw my attention.

It began to disturb me. I’d spent a lot of time reading back issues of Reader’s Digest as a child, and every few months the magazine would print an essay on the mind-rotting powers of television. We waste countless hours in front of the TV, went a common refrain, hours that might be better spent learning a foreign language or reading Homer’s Odyssey. It was enough to make me give up watching TV entirely at the age of twelve. But that had been years ago, before the advent of the internet and smartphones, before we all carried hypnotic devices in our back pockets. Now the seductive allure of old media seemed positively quaint in comparison.

Growing up I had never struggled with reading. Now I borrowed books from the library and they sat on the floor gathering dust. In time it dawned on me: if I was no longer reading, then other people were likely no longer reading. Suddenly it began to seem like reading itself was in grave danger.

One of the more fateful library encounters of my life took place in the sixth grade, when a middle school librarian shoved into my hands a paperback copy of a short novel by Ray Bradbury. The novel was entitled Fahrenheit 451, and it concerned a near-future America in which books are forbidden by law, incinerated by “firefighters” whose job is to start fires.

Bradbury’s novel, published in 1953, is often unfairly dinged as “a book about censorship.” But that, I think, is to miss the point of the story. The America in which the events of the book take place is more hedonistic than oppressive, more Huxley than Orwell. TV screens take up entire walls of houses (Mildred, the wife of the firefighting protagonist, Guy Montag, wants to install a fourth one). Kids idle away their time playing bumper cars at the local amusement park and murdering other kids for sport. It is a world besotted with entertainment, a world of perpetual noise and distraction. And, importantly, books were abolished not by a censorious government but by a public that grew tired of thinking, and found what was written in the books distasteful.

Midway through the book Captain Beatty, Montag’s mad boss, gives a brief lecture on the origins of the firefighters and the abolition of reading:

“More cartoons in books. More pictures. The mind drinks less and less. Impatience … Magazines became a nice blend of vanilla tapioca. Books, so the damned snobbish critics said, were dishwater. No wonder books stopped selling, the critics said. But the public, knowing what it wanted, spinning happily, let the comic books survive. And the three-dimensional sex magazines, of course. There you have it, Montag. It didn’t come from the Government down. There was no dictum, no declaration, no censorship, to start with. Technology, mass exploitation, and minority pressure carried the trick, thank God.”

Books couldn’t compete with the parlor screens. Books offended this or that pressure group. Books spoke disquieting truths about the human condition; they obstructed the central goal of all human endeavors, which is to be happy, happy, happy! all the time. And so they had to go.

In an important book-length essay, Amusing Ourselves to Death, written in 1985, the media critic Neil Postman argued that Brave New World was the most prophetic of the great dystopian novels because Huxley foresaw that “people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.”[iii] But I would argue that Fahrenheit 451 is the book that speaks most directly to our current moment. Fully half of American adults didn’t read a book, any book, in the past year. One-third of American eighth-graders are unable to read at grade level, the lowest percentage in the history of the survey. And there seems to be a growing consensus—best articulated by Jonathan Haidt in his book The Age of Anxiety—that the ubiquity of devices is at least partly to blame. There are other factors at play—COVID school closures, the loss of phonics instruction in grade school. But when students at Columbia and Yale, some of the brightest young minds of their generation, are struggling to read materials for class because they never had to read a book in middle or high school[iv], when professors are no longer assigning books like Moby-Dick because students can’t get through them, it seems clear we’ve entered the post-literate world Bradbury warned was coming all those years ago. And, unlike in the 1990s, popular culture seems at times actively hostile to the act of reading. (“F--- reading and everyone who can do it,” said the rapper formerly known as Kanye West in a recent tweet.) When ease and entertainment become the highest goods, knowledge and critical thinking suffer. And the wonderful old book, still our greatest technology, falls into shadow.

And as a veteran booklover, that breaks my heart.

I worry that my experience as an undergrad—of being let loose in a school library and going absolutely feral—is becoming uncommon. I’m afraid higher education has become so oriented towards being competitive in the job market that many students miss out on the best part of the college experience: the self-education that accrues via random excursions through the stacks.

I know that most folks have a more casual relationship to books, and I don’t want to give the impression that I think the only books you should read are classics. I encourage the reading of classics because I think they’re enjoyable and rewarding (as might be expected of books featuring gigantic hounds, cave-dwelling one-eyed monsters and ladies with snakes for hair). But more and more I’m just glad to see people reading. I don’t care if you’re reading Jack London or Jack Reacher; in fact, I prefer Jack Reacher. I just want you to read. I want you to know the joy and satisfaction that books can bring. I want you to experience the pleasures of the world’s most rewarding pastime.

“Reading has long been a necessity of everyday life for ordinary people,” writes Jonathan Rose in his book The Intellectual Life of the British Working-Classes, which chronicles the culture of autodidacts—those who, having little or no formal education, endeavored to teach themselves by constant reading—that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Welsh miners and millworkers formed study groups for the purpose of reading Hardy, Dickens, Eliot, Gaskell and Gibbon in community. Scottish shepherds created circulating libraries; watch- and cabinet-makers queued up to see George Bernard Shaw debate G. K. Chesterton; the sons and daughters of lift operators taught themselves Greek and Latin, and read Madame Bovary and Moby-Dick in Everyman’s editions. “A great uncle (whom I never knew),” Rose writes, “was a Bronx garment worker who spent much of the Great Depression reading … classics in translation from The Merchant of Venice to Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea.”[v] It was not unusual for working-class people to exhibit voracious reading habits in the years before the Second World War. Having been denied access to literacy and education for so long, they displayed an intellectual curiosity seldom equaled in history.

I don’t believe the men and women of a century ago were inherently smarter than we are. I believe we could build a reading culture in our time and place to rival theirs. But before we can do that, because it’s no longer obvious to many people, we first need to establish why the reading of books is fun and important, and why they can change your life.

And that’s what I intend to demonstrate in this book. By raving about some of my favorite works of literature, and the joys of reading more generally, I hope to show that it’s still possible in this day and age to be mad about books. I don’t consider myself an especially brilliant person; I just enjoy reading, and I believe anyone with a spirit of curiosity and a willingness to learn can come to love reading. C. S. Lewis described himself as “a product of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes, and the noise of wind under the tiles. Also, of endless books”[vi]—and I believe it’s still possible to live that kind of life. In these pages we’ll discover how.

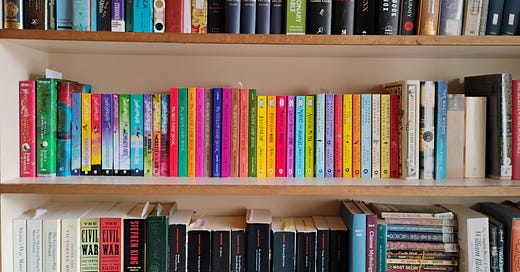

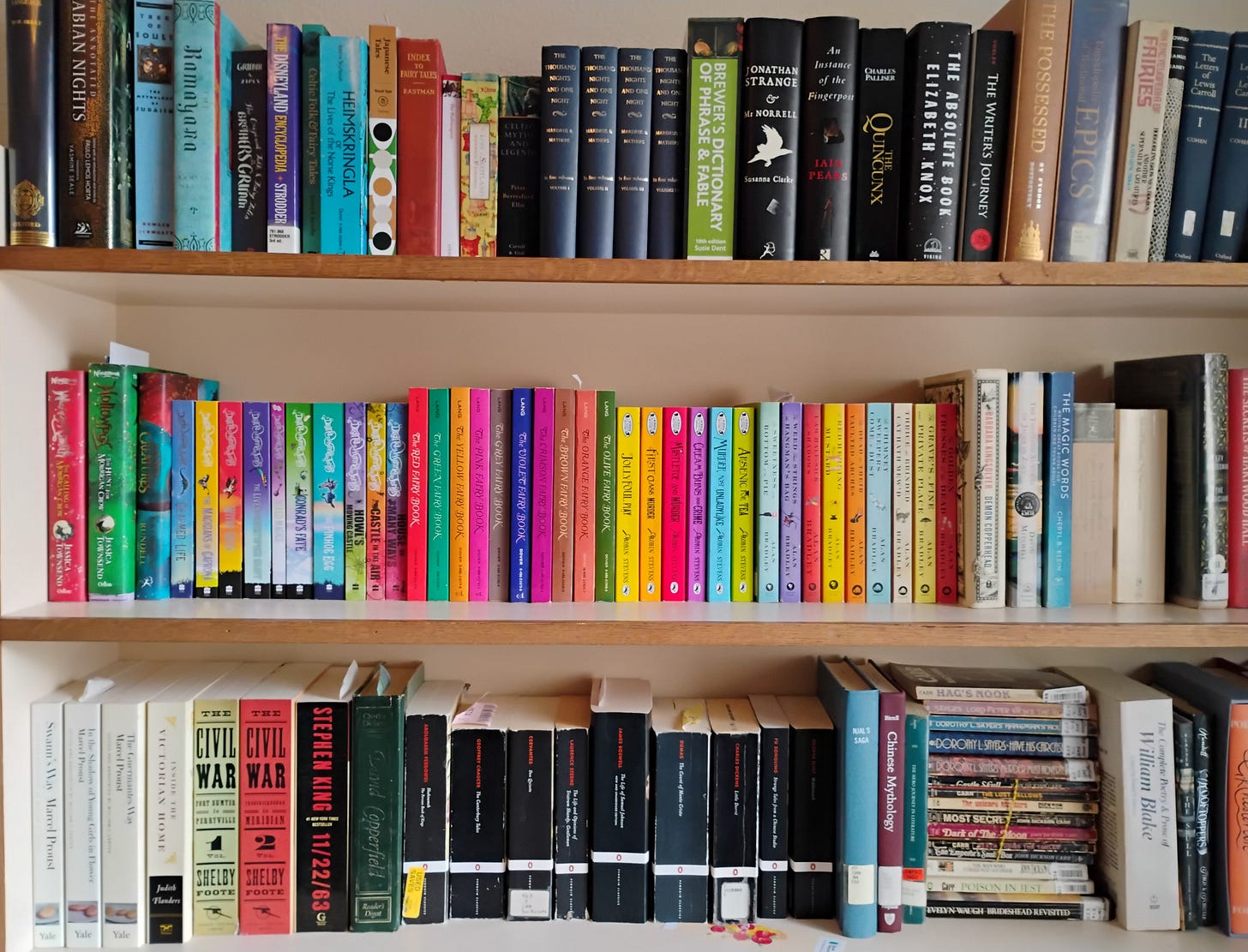

Oh, and if you were wondering—I did eventually recover from my reading slump. I learned how to master the phone instead of being mastered by it. I married a lovely fellow Dickensian who lived within a quarter-mile of a university library and together we began building a bookish life. I have yet to read a more purely enjoyable book than The Pickwick Papers, but I haven’t given up the search yet. If you happen to know of a better one, do let me know.

In the meantime, here are a few trinkets salvaged from the scrap-heap of a lifetime’s reading.

[i] Anderson, Sam. “The World of Charles Dickens, Complete with Pizza Hut.” The New York Times, February 7, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/12/magazine/dickens-world.html

[ii] Shakespeare, William. King Lear, 3.4.10-11

[iii] Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. 1985. New York, Viking.

[iv] Horowitch, Rose. “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.” The Atlantic, October 1, 2024. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/

[v] Rose, Jonathan. The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, Third Edition. Yale University Press, 2021.

[vi] Lewis, C. S. Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life. New York, Harcourt, Bruce, 1956.

Dear Boze, thanks for the trek through the stacks you just gave me. I had a frog pond in my backyard at our last house, where the frogs were named for Dickens’ characters - Smallweed, Uriah Heap, Artful Dodger, and my favorite, Judy-Shake-Me-Up. The charm that Dickens has brought to our lives is immeasurable & I love to meet others who grok that. I am decades older than you are, I think, but also grew up not knowing we were poor because there were books. I’ve been reading your tweets for years (now on Bluesky) & look forward to reading longer Substack pieces. Take care. -kimmie

Wonderful, thank you.